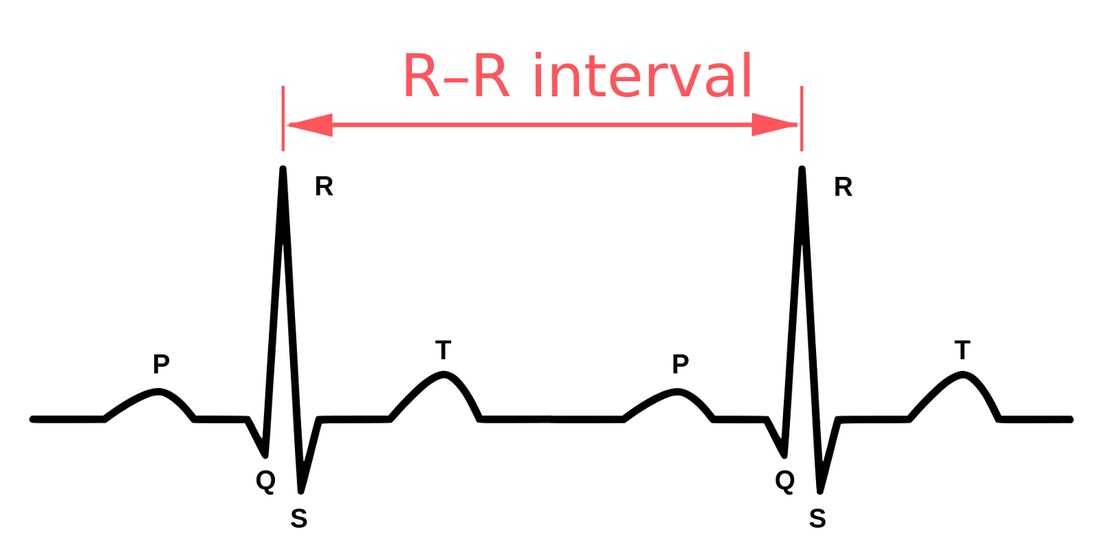

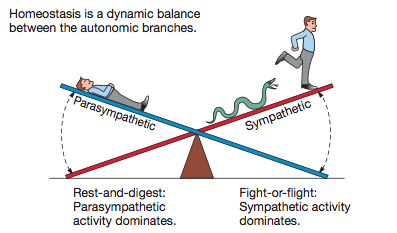

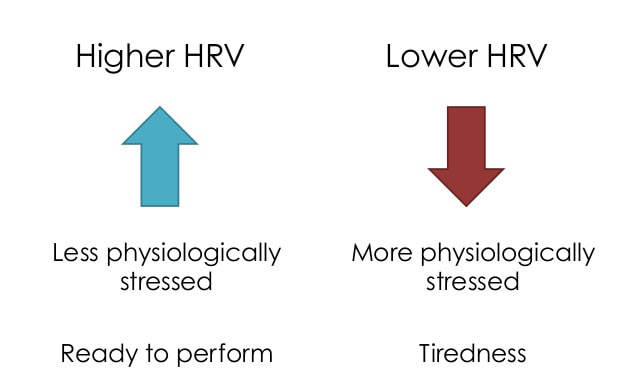

Have you ever wondered what the health impact of a stressful day was? Will you perform well during your long run or training session tomorrow morning? Is there anything you can do today that would improve your ability to have a better day tomorrow? HRV may be a piece of data that could help you answer these questions. What is HRV? HRV is simply a measure of the variation in time between each heartbeat, also known as the RR interval. This variation is controlled by a primitive part of the nervous system called the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS works regardless of our desire and regulates, among other things, our heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, and digestion. The ANS is subdivided into two large components, the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous system, also known as the fight-or-flight mechanism and the relaxation response. The brain is constantly processing information in a region called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus, through the ANS, sends signals to the rest of the body either to stimulate or to relax different functions. It responds not only to a poor night of sleep, or that sour interaction with your boss, but also to the exciting news that you got engaged, or to that delicious healthy meal you had for lunch. Our body handles all kinds of stimuli and life goes on. However, if we have persistent instigators such as stress, poor sleep, unhealthy diet, dysfunctional relationships, isolation or solitude, and lack of exercise, this balance may be disrupted, and your fight-or-flight response can shift into overdrive. Why Monitor HRV? HRV is a noninvasive way to identify these ANS imbalances. If a person’s system is in more of a fight-or-flight mode, the variation between subsequent heartbeats is low. If one is in a more relaxed state, the variation between beats is high. In other words, the healthier the ANS the faster you are able to switch gears, showing more resilience and flexibility. Over the past few decades, research has shown a relationship between low HRV and worsening depression or anxiety. A low HRV is even associated with an increased risk of death and cardiovascular disease (Buccelletti et al., 2009; Tsuji et al., 1994). People who have a high HRV may have greater cardiovascular fitness and be more resilient to stress. HRV may also provide personal feedback about your lifestyle and help motivate those who are considering taking steps toward a healthier life. It is fascinating to see how HRV changes as you incorporate more mindfulness, meditation, sleep, and especially physical activity into your life. For those who love data and numbers, this can be a convenient way to track how your nervous system is reacting not only to the environment, but also to your emotions, thoughts, and feelings. Measuring HRV The gold standard to measure HRV is to analyze a long strip of an electrocardiogram, the test that occurs frequently in medical offices where wires are attached to the chest. But over the past few years, several companies have created heart rate monitors that sync with apps that do something similar. The accuracy of these methods is still under scrutiny, but the technology is improving substantially. A word of caution is that there are no agencies regulating these devices, thus they may not be as accurate as claimed to be. With that said, the easiest and cheapest way to check HRV is to buy a chest strap heart monitor (e.g., Polar H10) and download a free app (e.g., Elite HRV) to analyze the data. The chest strap monitor tends to be more accurate than wrist or finger devices. Check your HRV in the mornings after you wake up, a few times a week, and track for changes as you incorporate healthier interventions. Tracking HRV may be a great tool to motivate behavioral change for some. HRV measurements can help create more awareness of how you live and think, and how your behavior affects your nervous system and bodily functions. While it obviously can’t help you avoid stress, it could help you understand how to respond to stress in a healthier way. While there are questions about measurement accuracy and reliability, if you decide to use HRV as another piece of data, do not get too confident if you have a high HRV, or too scared if your HRV is low. Think of HRV as a preventive tool, a visual insight into the most primitive part of your brain. Increasing HRV Far from the metronome we might assume it to be, the healthiest heart beat follows a fractal pattern, with varying lengths of time separating each pulse (Tapanainen et al., 2002; Yaniv, Y., Lyashkov, A. E., Lakatta, E. G., 2013). A higher HRV suggests a relaxed, low-stress physiological milieu, while a lower HRV indicates a need for recovery, rest, and sleep. Therefore, in order to increase HRV, generally speaking, a more relaxed, low-stress environment is desirable. While there are a number of ways to reduce stress and increase relaxation, here are some examples that have been observed to increase HRV:

ReferencesBuccelletti, F., Gilardi, E., Scaini, E., Galiuto, L., Persiani, R., Biondi, A., Basile, F., Gentiloni Silveri, N. (2009). Heart rate variability and myocardial infarction: systematic literature review and metanalysis. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 13(4), pp.299-307. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19694345

Campos, M. (2017). Heart rate variability: A new way to track well-being - Harvard Health Blog. [online] Harvard Health Blog. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/heart-rate-variability-new-way-track-well-2017112212789 [Accessed 19 Apr. 2018]. Da Silva, S. A. F., Guida, H. L., dos Santos Antonio, A. M., de Abreu, L. C., Monteiro, C. B. M., Ferreira, C., … Valenti, V. E. (2014). Acute Auditory Stimulation with Different Styles of Music Influences Cardiac Autonomic Regulation in Men. International Cardiovascular Research Journal, 8(3), 105–110. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4109034/ Dimitriev, D. A., Dimitriev, A. D., Karpenko, Y. D., & Saperova, E. V. (2008). Influence of examination stress and psychoemotional characteristics on the blood pressure and heart rate regulation in female students. Human Physiology, 34(5), 617-624. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S0362119708050101 Fiorino, P., Evangelista, F., Santos, F., Magri, F., Delorenzi, J., Ginoza, M. and Farah, V. (2012). The Effects of Green Tea Consumption on Cardiometabolic Alterations Induced by Experimental Diabetes. Experimental Diabetes Research, 2012, pp.1-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/309231 Hintsanen, M., Elovainio, M., Puttonen, S., Kivimäki, M., Koskinen, T., Raitakari, O. and Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2007). Effort—reward imbalance, heart rate, and heart rate variability: the cardiovascular risk in young finns study. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 14(4), pp.202-212. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03002994 Kageyama, T., Nishikido, N., Kobayashi, T., Kurokawa, Y., Kaneko, T. and Kabuto, M. (1998). Long Commuting Time, Extensive Overtime, and Sympathodominant State Assessed in Terms of Short-Term Heart Rate Variability among Male White-Collar Workers in the Tokyo Megalopolis. INDUSTRIAL HEALTH, 36(3), pp.209-217. htttps://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.36.209 Krygier, J., Heathers, J., Shahrestani, S., Abbott, M., Gross, J. and Kemp, A. (2013). Mindfulness meditation, well-being, and heart rate variability: A preliminary investigation into the impact of intensive Vipassana meditation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89(3), pp.305-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.06.017 Lee, J., Park, B., Tsunetsugu, Y., Ohira, T., Kagawa, T. and Miyazaki, Y. (2011). Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health, 125(2), pp.93-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2010.09.005 Loerbroks, A., Schilling, O., Haxsen, V., Jarczok, M., Thayer, J. and Fischer, J. (2010). The fruits of ones labor: Effort–reward imbalance but not job strain is related to heart rate variability across the day in 35–44-year-old workers. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(2), pp.151-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.03.004 Nesvold, A., Fagerland, M., Davanger, S., Ellingsen, Ø., Solberg, E., Holen, A., Sevre, K. and Atar, D. (2011). Increased heart rate variability during nondirective meditation. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 19(4), pp.773-780. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741826711414625 Patel, A. (2013). Cardiovascular Benefits of Forgiveness in Women: A Psychophysiological Study. The Ohio State University. Department of Psychology Undergraduate Research Theses. https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/54552/Patel_Thesis_2013.pdf?sequence=1 Patil, S. G., Mullur, L. M., Khodnapur, J. P., Dhanakshirur, G. B., Aithala, M. R. (2013). Effect of yoga on short-term heart rate variability measure as a stress index in subjunior cyclists: a pilot study. Indian Journal Physiological Pharmacology, 57(2), pp.153-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24617165 Sauder, K., Skulas-Ray, A., Campbell, T., Johnson, J., Kris-Etherton, P. and West, S. (2013). Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation on Heart Rate Variability at Rest and During Acute Stress in Adults With Moderate Hypertriglyceridemia. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(4), pp.382-389. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318290a107 Tapanainen, J., Thomsen, P., Køber, L., Torp-Pedersen, C., Mäkikallio, T., Still, A., Lindgren, K. and Huikuri, H. (2002). Fractal analysis of heart rate variability and mortality after an acute myocardial infarction. The American Journal of Cardiology, 90(4), pp.347-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02488-8 Tharion, E., Parthasarathy, S., & Neelakantan, N. (2009). Short-term heart rate variability measures in students during examinations. Natl Med J India, 22(2), 63-66. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19852338 Török, T., Rudas, L., Kardos, A., Paprika, D. (1998). The effects of patterned breathing and continuous positive airway pressure on cardiovascular regulation in healthy volunteers. Acta Physiologica Hungarica, 85(1), pp.1-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9530431 Tsuji, H., Venditti, F., Manders, E., Evans, J., Larson, M., Feldman, C. and Levy, D. (1994). Reduced heart rate variability and mortality risk in an elderly cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 90(2), pp.878-883. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.90.2.878 Tyagi, A., & Cohen, M. (2016). Yoga and heart rate variability: A comprehensive review of the literature. International Journal of Yoga, 9(2), 97–113. http://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.183712 Valenti, V., Guida, H., Campos, M., Knap, A., Vanderlei, L., Ferreira, C., de Abreu, L. and Roque, A. (2013). The effects of different styles of musical auditory stimulation on cardiac autonomic regulation in healthy women. Noise and Health, 15(65), p.281. https://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.113527 Yaniv, Y., Lyashkov, A. E., & Lakatta, E. G. (2013). The fractal-like complexity of heart rate variability beyond neurotransmitters and autonomic receptors: signaling intrinsic to sinoatrial node pacemaker cells. Cardiovascular Pharmacology: Open Access, 2, 111. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4690533/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The Awareness domain contains research, news, information, observations, and ideas at the level of self in an effort to intellectualize health concepts.

The Lifestyle domain builds off intellectual concepts and offers practical applications.

Taking care of yourself is at the core of the other domains because the others depend on your health and wellness.

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed