Stress: the perception of threat; a collective term used to describe the many social, psychological, and physiological factors that cause neurochemical changes within the body.

Stress is very often the root of many people's problems, whether they recognize it or not. You may have heard that someone is "under too much stress." You, too, may feel this way. But what exactly is stress? How can some withstand more stress than others? Is stress always a bad thing? Let's take a look.

What is Stress?

You probably think of stress as inherently bad, but this is not always the case. Just as bones and muscles need physical exercise to stay strong, we also need certain amounts of stress to stay healthy. Believe it or not, a complete lack of stress would not be a good thing. There are six major types of stress, each of which can have "good" or "bad" effects.

- Physical stress

- Chemical stress

- Electromagnetic stress

- Psychic of Mental stress

- Nutritional stress

- Thermal stress

Physical Stress

The Good: |

The Bad: |

Physical stress in the form of movement or exercise is very beneficial. The actual stress comes from loading the muscles and bones of our body under the influence of gravity. Astronauts in space need regular exercise in order to counteract the loss of bone and muscle mass that occurs under zero gravity conditions. Adequate movement and exercise also helps us to maintain an optimal metabolic rate, keeping us from becoming overweight. (Metabolic rate is the rate at which all physical and chemical processes take place within your body.) Considering that only about 8% of men and 3% of women exercise regularly, and that about 60% of Americans are overweight at present, it is evident that we are in great need of more of this good stressor (Mogadam, 2000). |

Over-exercising can be every bit as bad as not exercising enough. While under-exercising can contribute to becoming overweight and lead to metabolic dysfunction, over-exercising can cause immune system suppression (MacKinnon, 1999). This can lead to increased incidence of upper respiratory infection, chronic fatigue and a number of other ailments. Extreme exercise for athletes is often linked to poor performance and increased incidence of injury. Another form of adverse physical stress is poor posture. Posture has a significant influence on breathing, muscle function, joint health, circulation and internal organ support. When the body structure is not in balance, the rest of the system follows. |

Chemical Stress

The Good: |

The Bad: |

Our bodies are full of chemicals - naturally produced chemicals that are essential for health. The work of producing these key chemicals is a necessary stress for the body. For example, when your body systems are working correctly, exercise results in chemical adaptations in the form of hormonal changes that alter your biochemistry to increase protein synthesis, energy production and a myriad of other chemical reactions. The action of sunlight on the skin results in the production of vitamin D and the regulation of the hormones melatonin and cortisol - both chemical reaction. Plant and animal foods (ideally organically-cultivated) are made up of organic chemicals - vitamins, enzymes, proteins and fats that we need to survive. |

In this day and age, we are bombarded with thousands upon thousands of chemicals that were not around one hundred years ago. Many of these chemicals are synthetic, and our bodies do not have mechanisms to neutralize them. Synthetically manufactured medical drugs, such as aspirin, are among the most common forms of unfavorable chemical stress. Other examples of dangerous chemical stressors are agricultural chemicals such as pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and certain fertilizers. These chemicals are often made from the same formulas used to make biological weapons, yet nearly two billion pounds of these chemicals are sprayed on our foods each year in the U.S. alone (Kimbrell, 2002). Many health problems have been linked to this form of chemical stress. |

Electromagnetic Stress

The Good: |

The Bad: |

Indeed, one the most beneficial forms of electromagnetic stress is sunlight. Without sunlight, we simply would not be alive. The electromagnetic field of the earth is also a good form of this kind of stress. This invisible field helps control the rhythm of our hormones and other physiological function. A common example of the earth's electromagnetic effects can be experienced when weather patterns change. At the onset of a thunderstorm, many people feel changes in their joints, muscles and even their moods. |

The most obvious form of bad electromagnetic stress is over-exposure to sunlight, resulting in sunburn. In Australia and New Zealand, the ultraviolet rays are poorly filtered by the thin ozone layer. This means you can begin to burn in under 12 minutes on a summer day. Most people know that overexposure to radiation such as medical X-rays can also be harmful to your health. Often overlooked is the extremely low frequency (ELF) pollution emitted by electronic devices such as computers, cell phones and towers, WiFi routers, microwave ovens, electric motors, your TV, and even electric blankets and heaters. Many of these forms of stress are insidious, causing dysfunction in your hormonal and autonomic nervous system. |

Psychic or Mental Stress

The Good: |

The Bad: |

Thinking and using your mind productively represents good psychic or mental stress. Having a plan or setting goals in your life and doing the work to achieve them is also a positive form of this stress. Other examples include overcoming adversity to become a stronger, better person. Without psychic stress, our minds would not fully develop. |

A common form of bad psychic stress is focusing on things that you do not want in life instead of what you do want. Other forms of psychic stress include verbal abuse from others, studying so much that your mental faculties begin to diminish, and challenging religious or spiritual beliefs that are imposed upon you - even if self-imposed. Being rushed or taking on more work or responsibility than you can manage will also produce unhealthy psychic stress. |

Nutritional Stress

The Good: |

The Bad: |

Eating in accordance personal diet type, eating organic foods, and not over- or under-eating are all representative of good nutritional stress. In these instances, the term stress is used to indicate the stress of digestion, assimilation, metabolism of foods. For example, your body must be stressed with the challenge of extracting the nutrition from your food or it will become weak, much like a person's muscles become weak if you put them in a sling or cast and do not use them. |

Eating too much, too little, or eating the wrong food proportions for your personal diet type are unhealthy forms of nutritional stress. Consuming foods with toxins such as pesticides, herbicides, food preservatives, colorings, thickeners, emulsifiers and the like can be very stressful to the body as well. This type of stress from food may be responsible for a large percentage of disease today. |

Thermal Stress

The Good: |

The Bad: |

Maintaining your body temperature at 98.6°F (37°C) is the most obvious of the good thermal stressors. When it is hot or cold outside, the thermoregulatory system is stressed in order to keep your internal temperature constant. It is good to stress this system now and again to maintain its dynamic capacity. |

Anything that burns you is a form of adverse thermal stress. In addition, the opposite thermal stress would be anything that brings your body temperature too low for an extended period of time. |

Bioaccumulation: Internal and External Stressors

External stressors are forms of tension that stress the body from the outside, such as sunlight, physical pain (caused by injury or other external forces), emotional trauma, and toxic chemical exposure.

Internal stressors come from within the body and are most often the reaction to external stressors. For example, if you are repeatedly exposed to toxic chemicals, cancer or other diseases may develop. Even if the toxic chemicals are removed, cancer will continue to stress the body systems. If you are in an unhappy relationship, an external situation, you will experience a chronic stress response within the body. Chronic stressors cause elevated stress hormones in the body, leading to immune suppression, the inability to heal and eventually to disease.

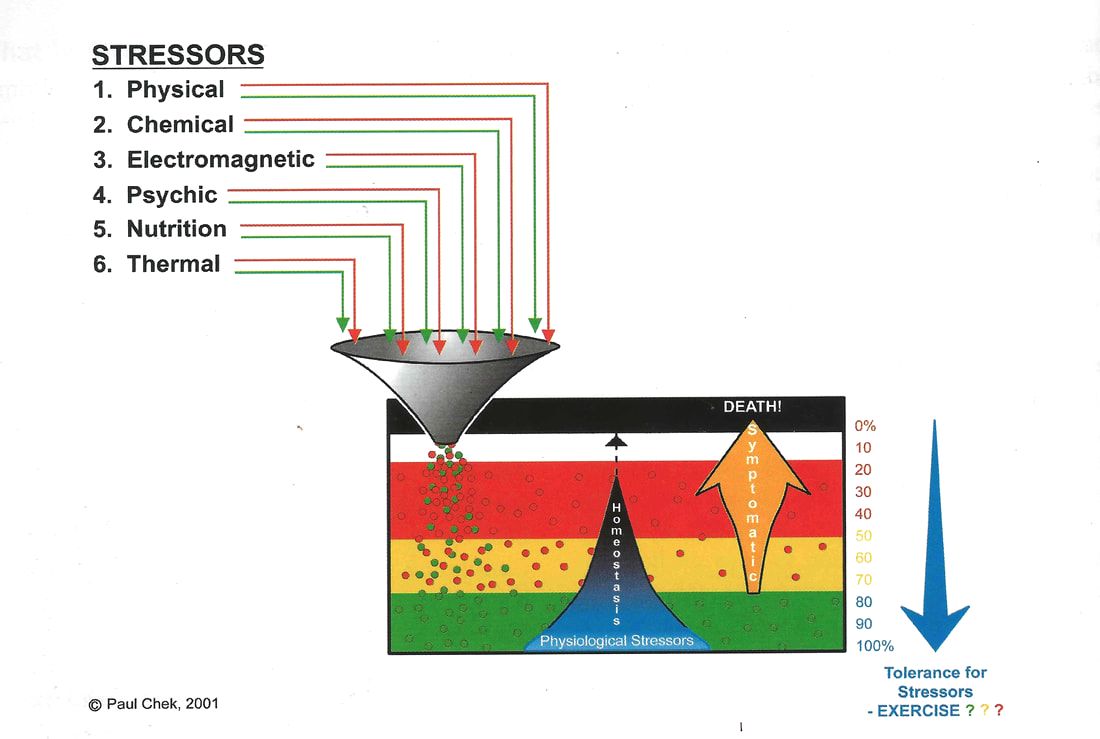

Stress is perceived or interpreted by key control systems of the body - limbic/emotional, hormonal, visceral, nervous, musculoskeletal and subsystems. The green arrows in Figure 1 represent good stressors that are used by the body to regulate and maintain optimal bodily functions. The bad or excessive stressors (indicated by the red arrows) can throw the body out of balance. The nervous system plays an important role here. All the stressors are funneled together and processed by the nervous system to create an overall stress picture in the body. As shown in Figure 1, you will stay in the "green zone" (in homeostasis, or balance) if the total stress picture is favorable for your body. When in this zone, response to external stressors such as exercise is favorable. The ability to bounce back from potentially damaging stressors is also much improved.

If for any reason the sum of all the stressors places too great a demand on your body, you will begin to fall out of balance and move into the "yellow zone". If you do not make the necessary changes to reduce the primary stress or stressors, your body begins to break down and you progressively move into the "red zone". Your ability to cope with external stressors such as exercise is progressively diminished, as is your ability to tolerate internal stressors, such as disease. The further you get into the "red zone", the more easily disease will be able to take hold.

Internal stressors come from within the body and are most often the reaction to external stressors. For example, if you are repeatedly exposed to toxic chemicals, cancer or other diseases may develop. Even if the toxic chemicals are removed, cancer will continue to stress the body systems. If you are in an unhappy relationship, an external situation, you will experience a chronic stress response within the body. Chronic stressors cause elevated stress hormones in the body, leading to immune suppression, the inability to heal and eventually to disease.

Stress is perceived or interpreted by key control systems of the body - limbic/emotional, hormonal, visceral, nervous, musculoskeletal and subsystems. The green arrows in Figure 1 represent good stressors that are used by the body to regulate and maintain optimal bodily functions. The bad or excessive stressors (indicated by the red arrows) can throw the body out of balance. The nervous system plays an important role here. All the stressors are funneled together and processed by the nervous system to create an overall stress picture in the body. As shown in Figure 1, you will stay in the "green zone" (in homeostasis, or balance) if the total stress picture is favorable for your body. When in this zone, response to external stressors such as exercise is favorable. The ability to bounce back from potentially damaging stressors is also much improved.

If for any reason the sum of all the stressors places too great a demand on your body, you will begin to fall out of balance and move into the "yellow zone". If you do not make the necessary changes to reduce the primary stress or stressors, your body begins to break down and you progressively move into the "red zone". Your ability to cope with external stressors such as exercise is progressively diminished, as is your ability to tolerate internal stressors, such as disease. The further you get into the "red zone", the more easily disease will be able to take hold.

Image by Chek, P. Figure 1: All stressors are funneled together within your body and processed by your nervous system. The green arrows represent good stressors, while the red arrows signify bad stressors. Image accumulating all of your stressors for a week or a month. The higher your levels of stress, the harder it is on your body.

Researchers have discovered that life changes (either personal or work-related) as a source of stress can eventually lead to disease. The body's response to any stress, whether caused by events perceived as positive or negative, is to mobilize it's defenses to maintain homeostasis.

Personality traits, rotating shift work, work environment (e.g., exposure to loud noise, excessive or extreme temperatures, chemicals, vibration, or extreme lighting) safety hazards, social factors, and recent life changes, are a few of the known risk factors linked to stress. Although many factors causing stress have been studied, the ability to predict a stress response in any given individual remains poor.

A growing body of evidence supports a strong correlation between stress response and the manifestation of various disorders. How stress produces disease is frequently debated and the exact pathophysiologic mechanism remains unknown. One theory holds that certain kinds of stress are consistently likely to produce given physiologic responses, and, consequently, specific pathologic states. Another viewpoint is that stress is "non specific" and that personal factors such as conditioning and heredity determine which organ system, if any, will be affected by a variety of stressors. A given individual may have a specific susceptible organ that will be the target of a variety of stresses; thus, some people are gastrointestinal reactors, others are cardiac or muscle tension reactors. Stress may be viewed as a nonspecific force that exacerbates existing disease states (Goodman & Boissonnault, 2003).

Personality traits, rotating shift work, work environment (e.g., exposure to loud noise, excessive or extreme temperatures, chemicals, vibration, or extreme lighting) safety hazards, social factors, and recent life changes, are a few of the known risk factors linked to stress. Although many factors causing stress have been studied, the ability to predict a stress response in any given individual remains poor.

A growing body of evidence supports a strong correlation between stress response and the manifestation of various disorders. How stress produces disease is frequently debated and the exact pathophysiologic mechanism remains unknown. One theory holds that certain kinds of stress are consistently likely to produce given physiologic responses, and, consequently, specific pathologic states. Another viewpoint is that stress is "non specific" and that personal factors such as conditioning and heredity determine which organ system, if any, will be affected by a variety of stressors. A given individual may have a specific susceptible organ that will be the target of a variety of stresses; thus, some people are gastrointestinal reactors, others are cardiac or muscle tension reactors. Stress may be viewed as a nonspecific force that exacerbates existing disease states (Goodman & Boissonnault, 2003).

Overview of the Nervous System

The nervous system is a combination of two systems that work together. The peripheral nervous system controls conscious movement and the central nervous system, which contains the autonomic nervous system (ANS), controls those actions in the body that you do not normally regulate through conscious thought, such as digestion and elimination of food, the release of hormones, sweating, and the modulation of blood flow to different muscles and organs.

The ANS is further split into two branches:

Both systems of the ANS are always working, it is just a matter of which branch exerts the greatest influence over your physiology at any given time. When activated, the SNS produces a fight-or-flight response. Whenever threatened, our natural inclination is either to "fight" to protect ourselves, or "flight" - to run for our lives. A potentially stressful situation will activate the SNS and prepare your body for fighting or running by producing the following responses, among others, within your body:

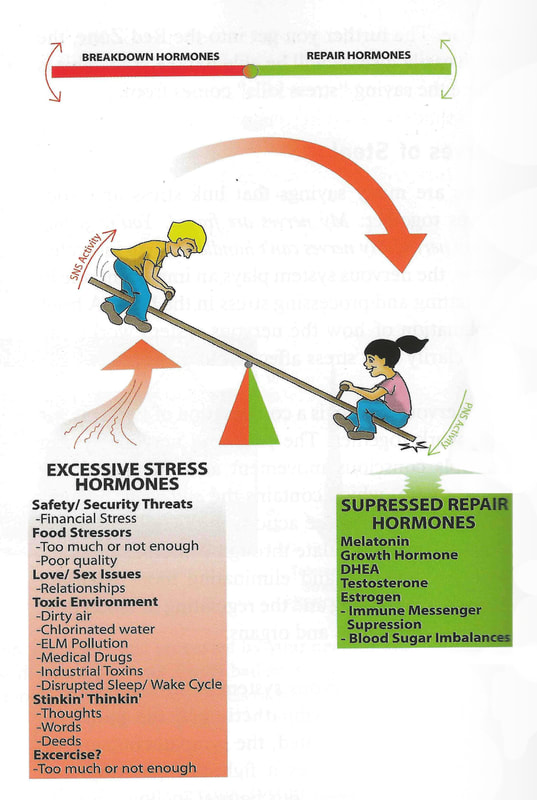

The SNS is often referred to as the catabolic (destructive metabolism) system. When your fight-or-flight response is activated, levels of the stress hormone cortisol are elevated. If cortisol levels are above normal, your growth and repair hormones are suppressed. Long-term over-production of cortisol leads to a break down of body tissues and fatigue of the adrenal glands. As the adrenals fatigue, the body is unable to maintain balance between stress and immune hormones, which leads to immune system dysfunction. Many years of chronic stress results in disease and premature death

The ANS is further split into two branches:

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS)

- Parasympathetic nervous system (PNS)

Both systems of the ANS are always working, it is just a matter of which branch exerts the greatest influence over your physiology at any given time. When activated, the SNS produces a fight-or-flight response. Whenever threatened, our natural inclination is either to "fight" to protect ourselves, or "flight" - to run for our lives. A potentially stressful situation will activate the SNS and prepare your body for fighting or running by producing the following responses, among others, within your body:

- Release of stress hormones that elevate your heart rate and blood pressure

- Shunting of blood away from your internal organs to the skin and muscles - greatly reducing or stopping all digestive and eliminative processes.

- Increased sweating

The SNS is often referred to as the catabolic (destructive metabolism) system. When your fight-or-flight response is activated, levels of the stress hormone cortisol are elevated. If cortisol levels are above normal, your growth and repair hormones are suppressed. Long-term over-production of cortisol leads to a break down of body tissues and fatigue of the adrenal glands. As the adrenals fatigue, the body is unable to maintain balance between stress and immune hormones, which leads to immune system dysfunction. Many years of chronic stress results in disease and premature death

Sympathetic Nervous System: Part of the autonomic nervous system, which when activated (often as a response to stress) results in the release of stress hormones, increasing your heart rate and blood pressure while decreasing digestive and repair processes - often referred to as a "fight-or-flight" response.

Parasympathetic Nervous System: Part of the autonomic nervous system which supports digestive and repair processes, opposes the effects of the sympathetic nervous system.

Parasympathetic Nervous System: Part of the autonomic nervous system which supports digestive and repair processes, opposes the effects of the sympathetic nervous system.

When repeatedly stressed, you are continually mobilizing your energy reserves for immediate use. At the same time, the PNS is suppressed. The PNS stimulates digestion, metabolism and the release of tissue building hormones (DHEA, growth hormone, testosterone, estrogen, BDNF, and others. If the PNS is constantly shut down, you will be unable to effectively digest foods and repair your body. This over-stimulation of the SNS is a common cause of many chronic fatigue states and chronic disease processes, not the mention emotional imbalances and distress.

Here are some examples of stimuli that may activate your SNS or PNS:

Here are some examples of stimuli that may activate your SNS or PNS:

|

Stimuli Leading to SNS Activation

|

Stimuli Leading to PNS Activation

|

If you are able to keep your ANS within the "green zone", when a stressor does occur, you are capable of adapting quickly.

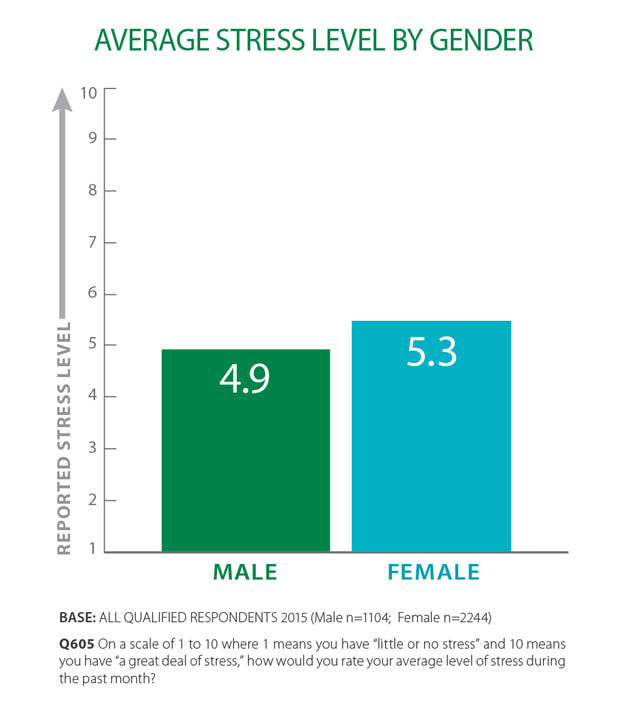

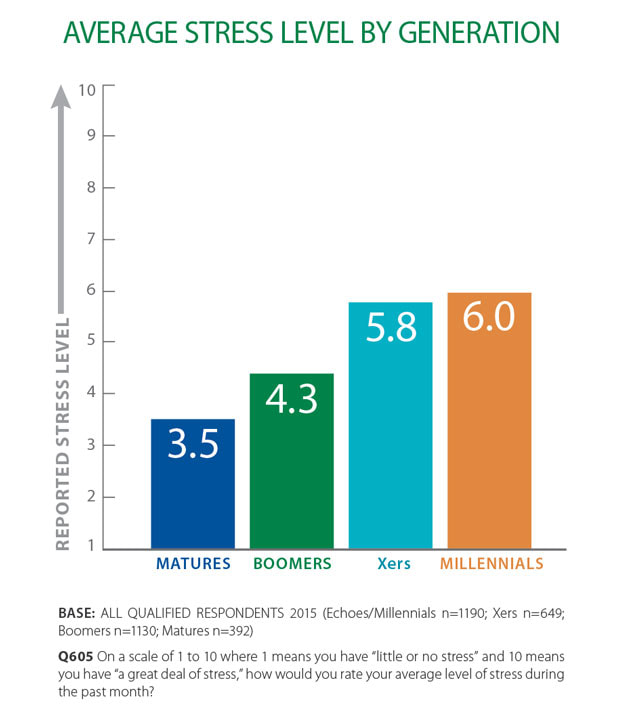

Prevalence of Stress

According to the American Psychological Association, 78% of adults reported experiencing at least one symptom of stress in 2015. 67% of adults have reported that they have received a diagnosis for at least one chronic illness. In addition, adults spend an average of 6.4 hours a day in sedentary activities — sitting or lying, without much movement — including time spent at a desk, watching TV or on a computer. 45% of adults report doing so for 6 to 12+ hours a day (American Psychological Association, 2016).

Causes of Stress

It is widely recognized that stress causes disease. When something is perceived as stressful, the body is stimulated to get ready for flight or fight (the sympathetic response) and the relaxing, healing, restoring aspect of ourselves (the parasympathetic) is suppressed. The stress response is about action now - do something quickly to get out of danger. It is not favorable to reflection, to feeling the complexity of our deepest feelings, to figuring out deeper meanings, meditating on the meaning of life, or planning for the future in a rational and connected way.

Our modern societies are incredibly stressful - fast-paced and furious, with little time for rest and recuperation. The balance is definitely tipped toward the sympathetic and away from the parasympathetic for most of us. In addition, the kind of activities many of us are engaged in, characterized by a lack of involvement in the body and overuse of the cognitive, brain-based intellectual view of the world leads to a loss of coherence. "Coherence" is a term used to refer to connection, harmony, order, and structure without and among systems (Waller, 2010).

As for the sources of their stress, adults are more likely to find family responsibilities stressful than they have in the past. Since 2007, researchers have found that money and work are the top two sources of very or somewhat significant stress (67% and 65% in 2015, respectively) (American Psychological Association, 2016).

Causes of stress include, but are not limited to:

Our modern societies are incredibly stressful - fast-paced and furious, with little time for rest and recuperation. The balance is definitely tipped toward the sympathetic and away from the parasympathetic for most of us. In addition, the kind of activities many of us are engaged in, characterized by a lack of involvement in the body and overuse of the cognitive, brain-based intellectual view of the world leads to a loss of coherence. "Coherence" is a term used to refer to connection, harmony, order, and structure without and among systems (Waller, 2010).

As for the sources of their stress, adults are more likely to find family responsibilities stressful than they have in the past. Since 2007, researchers have found that money and work are the top two sources of very or somewhat significant stress (67% and 65% in 2015, respectively) (American Psychological Association, 2016).

Causes of stress include, but are not limited to:

Money |

Work |

The economy |

Relationships |

Family responsibilities |

Health problems affecting family |

Personal health concerns |

Job stability |

Housing costs |

Personal safety |

Impacts of Stress

Findings that link immune and neuroendorcrine function may provide explanations of how the emotional state or response to stress can modify a person's capacity to cope with infection and influence the course of autoimmune disease. For example, ongoing stress causes a cascade of biochemical effects via the actions of hormones released from the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Cortisol (a toxic stress hormone in large amounts) is released from the adrenal glands, causing immunosuppression, that is, decreased numbers of white blood cells and antibodies, thus increasing vulnerability to infectious diseases, including viral-induced cancers (Goodman & Boissonnault, 2003).

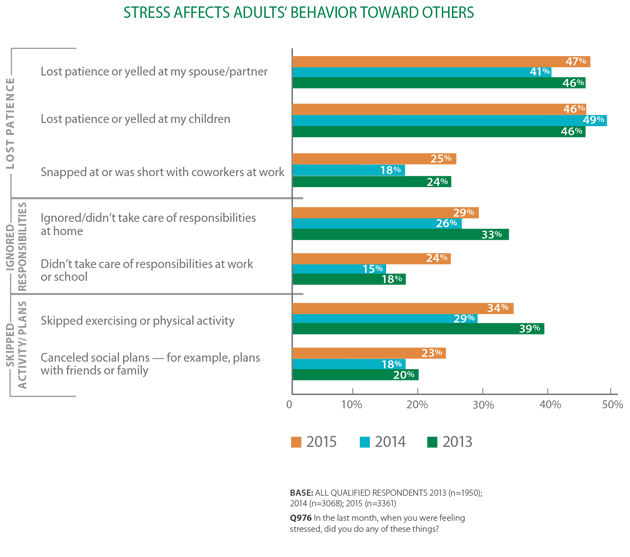

Stress greatly impacts adults’ health and behaviors, particularly unhealthy eating. Adults also are more likely to report changes in sleeping habits (33% vs. 27% in 2014), headaches (32% vs. 27% in 2014) and an inability to concentrate (27% vs. 23% in 2014) due to stress in the past month. In addition, nearly half of adults report lying awake at night due to stress in the past month. For many adults, stress affects their behavior toward others. Almost half of adults who have a spouse or partner report losing patience with or yelling at them in the past month when they were feeling stressed. In addition, nearly half of all of parents (defined as those with children under 18 living at home) report similar behavior with their children. One-quarter of those employed report snapping at or being short with co-workers because of stress (American Psychological Association, 2016).

Physical symptoms of stress include, but are not limited to:

Stress greatly impacts adults’ health and behaviors, particularly unhealthy eating. Adults also are more likely to report changes in sleeping habits (33% vs. 27% in 2014), headaches (32% vs. 27% in 2014) and an inability to concentrate (27% vs. 23% in 2014) due to stress in the past month. In addition, nearly half of adults report lying awake at night due to stress in the past month. For many adults, stress affects their behavior toward others. Almost half of adults who have a spouse or partner report losing patience with or yelling at them in the past month when they were feeling stressed. In addition, nearly half of all of parents (defined as those with children under 18 living at home) report similar behavior with their children. One-quarter of those employed report snapping at or being short with co-workers because of stress (American Psychological Association, 2016).

Physical symptoms of stress include, but are not limited to:

Irritability or anger |

Feeling nervous or anxious |

Fatigue |

Feeling depressed or sad |

Lack of interest, motivation, or energy |

Headache |

Feeling as though you could cry |

Upset stomach or indigestion |

Muscular tension |

Teeth grinding |

Changes in sex drive |

Chest tightness |

Feeling faint |

Changes in menstrual cycle |

Erectile dysfunction |

Understanding The Stress Response

Researchers have discovered that the human brain is actually composed of three brains (MacLean, 1972):

The reptilian and mammalian brain are actually functional units, yet fully integrated within our more modern human brain. The most important feature inherited from the reptilian and mammalian brain is our primary concern for our won safety, followed by our survival instinct to feed or seek sustenance. The reptilian perspective ranks procreation as the lowest priority.

Reptiles have little emotional capacity and live purely upon instinct. If a predator enter their territory they automatically act upon their fight or flight instincts, because they innately know their lives depend upon their reaction. As humans we have a unique capacity to ignore our instincts. When stressful situations arise, we often think irrationally. For example, we ignore our primary reptilian instinct to be secure by spending money that we do not have on cars, jewelry, and other status symbols. In this case, we are sacrificing financial security for an improved social status - what our mammalian brain thinks of as rank. Unfortunately, many people will sacrifice their health by ignoring the second more important concern of the reptilian brain - eating healthy food. They compromise their well-being by eating cheap, poor-quality foods so they can afford other material possessions to improve their status.

Reptiles and mammals engage in sex for purposes of perpetuating their species, but only when they are safe and well fed. Many humans, on the other hand, prioritize sex over health and safety. An overly stressed body will automatically response by decreasing the sex drive to preserve energy for the first and second reptilian priorities. If you are suffering from a low sex drive, you will need to get your reptilian priorities of security and sustenance sorted out.

Ignoring our reptilian and mammalian (paleomammalian) instincts does very little to improve our stress levels. Modern society is driven by new brain desires to look better and have more material goods, often at the expense of physical and mental health, resulting in more stress and disease.

- the reptilain brain

- the mammalian (paleomammalian/"monkey") brain

- the new mammalian (neomammalian/"human") brain

The reptilian and mammalian brain are actually functional units, yet fully integrated within our more modern human brain. The most important feature inherited from the reptilian and mammalian brain is our primary concern for our won safety, followed by our survival instinct to feed or seek sustenance. The reptilian perspective ranks procreation as the lowest priority.

Reptiles have little emotional capacity and live purely upon instinct. If a predator enter their territory they automatically act upon their fight or flight instincts, because they innately know their lives depend upon their reaction. As humans we have a unique capacity to ignore our instincts. When stressful situations arise, we often think irrationally. For example, we ignore our primary reptilian instinct to be secure by spending money that we do not have on cars, jewelry, and other status symbols. In this case, we are sacrificing financial security for an improved social status - what our mammalian brain thinks of as rank. Unfortunately, many people will sacrifice their health by ignoring the second more important concern of the reptilian brain - eating healthy food. They compromise their well-being by eating cheap, poor-quality foods so they can afford other material possessions to improve their status.

Reptiles and mammals engage in sex for purposes of perpetuating their species, but only when they are safe and well fed. Many humans, on the other hand, prioritize sex over health and safety. An overly stressed body will automatically response by decreasing the sex drive to preserve energy for the first and second reptilian priorities. If you are suffering from a low sex drive, you will need to get your reptilian priorities of security and sustenance sorted out.

Ignoring our reptilian and mammalian (paleomammalian) instincts does very little to improve our stress levels. Modern society is driven by new brain desires to look better and have more material goods, often at the expense of physical and mental health, resulting in more stress and disease.

Traits and Functionality Associated with the Reptilian Brain

Traits and Functionality Associated with the Mammalian (paleomammalian) Brain

Traits and Functionality Associated with the Human (neomammalian) Brain

- Regulates breathing, heart rate, digestion, elimination, sleep/wake cycles, and temperature

- The four 'F's: fight, flight, feeding, and fornication

- Instinctual

- Ritualistic (performing the same functions at the same time of day, eating the same foods, behaving a given way during the different seasons)

- Defining hierarchy within a group and establishing space in the ecological niche

Traits and Functionality Associated with the Mammalian (paleomammalian) Brain

- Increased sense of subordination (rank, power, authority)

- Increased capacity for memory and learning

- Significant expansion of the emotional centers of the brain (playful moods, fright, passion, joy, sadness, females nurse and protect young)

Traits and Functionality Associated with the Human (neomammalian) Brain

- Rational thinking

- Capable of producing symbolic language, enabling intellectual activities such as reading, writing, and performing mathematical calculations

- The ability to generate ideas

- The ability to ignore reptilian and mammalian instincts

- Spiritual development

Old Brain Instincts |

New Brain Instincts |

|

Safety/Security |

Survival Territorial |

Financial gain Personal space Material addictions |

Feeding |

Satiety |

Addictive eating Emotional eating |

Sex/Appearance |

Procreation (only when the above needs are met) |

Lust/Desire/Emotion Status driven Procreation |

Solutions: Stress Management and Recovery Mechanisms

If stress is so bad for us, wouldn't we have built-in recovery mechanisms to help us offload its dangerous effects? Why, yes, in fact, we do. One of the most important recovery mechanisms for humans is to connect - we need to connect with ourselves, with our hearts, but with each other. Talking, sharing feelings, show our feelings with beloved others, is necessary for human health.

It is possible to change what our minds are focusing on. A good way to learn to take charge of your mind and your thinking is to learn meditation. Meditation has been the subject of more than 600 research studies. Regular meditation has been shown to increase creativity, increase EEG coherence of brain functioning, reduce stress in several ways, improve the health, reduce the negative effects of aging, improve relationships and self-confidence, improve productivity at work, and decrease crime, conflict, and violence (Waller, 2010).

It is possible to change what our minds are focusing on. A good way to learn to take charge of your mind and your thinking is to learn meditation. Meditation has been the subject of more than 600 research studies. Regular meditation has been shown to increase creativity, increase EEG coherence of brain functioning, reduce stress in several ways, improve the health, reduce the negative effects of aging, improve relationships and self-confidence, improve productivity at work, and decrease crime, conflict, and violence (Waller, 2010).

Here are some tips for managing stress:

- Identify your primary stressor: Focus on reducing stress in the area that is causing you the most stress. Generally, the priorities of reptilian brain are: security, sustenance and sex. Alleviating the chief stressor in your life often creates a domino effect, wiping out or dramatically reducing other stressors in succession.

- Make a plan: Make a specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic plan to address your biggest stressor and set a series of short-term goals, allowing you to clearly recognize progress as it is made. Look for current books, videos, or audio programs that address issues related to your key stressor and how to overcome it. Another effective method is to find someone who has already been successful at overcoming the challenge you now face. There is no better teacher than experience.

- Eat and drink right: Internal stressors only serve to magnify external stressors. Regardless of what your primary stressor may be, if you are not eating according to your personal diet type, you will not be able to effectively replace the stress hormones you are using on a daily basis, which only causes more stress to the body. Once you know your personal diet type, go out of your way to eat as much organically-produced food as possible - although be mindful of your consumption. The more conventionally farmed food you eat, the more toxins you are consuming. These toxic poisons create a significant stress at the metabolic level, and many of them have been linked to mental and emotional dysfunction. Dehydration is a common cause of internal stress. A reduction of as little as 1% of water content in your central nervous system can cause significant psychological disorders. Reducing your intake of coffee, tea, and sodas, plus drinking more high-quality water, is an easy way to start reducing the internal stress on your body.

- Move and exercise: Regular exercise can be a major tool to reduce stress. When performed correctly for your particular needs, exercise in the correct dose stimulates an anabolic (tissue growth and repair) environment. Your exercise program should be carefully constructed so as not to overstress your body.

- Mental exercise: Many successful individuals give credit to the power of positive thinking. Try harmonizing your thoughts, words, and actions with your goals and you may find that this will help decrease stress. Doing so is a good example of beneficial mental or psychic stress. Make sure you are talking and thinking about what you do want, rather than what you do not.

References

American Psychological Association. (2016). Stress in America: The Impact of Discrimination. [online] Available at: http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2015/impact-of-discrimination.pdf [Accessed 11 Aug. 2017].

Chek, P. (2004). How to eat, move and be healthy. San Diego, CA: C.H.E.K. Institute.

Goodman & Boissonnault. (2003). Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders.

Kimbrell, Andrew. (2002). Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture. Washington: Island Press.

MacLean, Paul. (1972). Man's Triune Brain in Evolution. Plenium Press.

MacKinnon. (1999). Advances in Exercise Immunology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Mogadam, Micheal MD. (2000). Radio interview, Don Bodenbach, San Diego, CA.

Waller, P. (2010). Holistic anatomy: an integrative guide to the human body. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Chek, P. (2004). How to eat, move and be healthy. San Diego, CA: C.H.E.K. Institute.

Goodman & Boissonnault. (2003). Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders.

Kimbrell, Andrew. (2002). Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture. Washington: Island Press.

MacLean, Paul. (1972). Man's Triune Brain in Evolution. Plenium Press.

MacKinnon. (1999). Advances in Exercise Immunology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Mogadam, Micheal MD. (2000). Radio interview, Don Bodenbach, San Diego, CA.

Waller, P. (2010). Holistic anatomy: an integrative guide to the human body. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.