To reduce stress using Fitness...

it is recommended to endure aerobic exercise – up to 30 min./bout, 3+ months

to reduce anxiety using Fitness...

researchers have found that aerobic exercise (low/moderate intensity; 30-70% max HR) and anaerobic exercise (30-50% max HR) effectively resulted in lowered state anxiety.

Green exercise, which is exercise in natural environments, known to provide physical and psychological health benefits, such as reducing stress and increased ability to cope with stress, reducing metal fatigue and improving concentration and cognitive function. Long-term exercise is usually associated with reductions in traits such as neuroticism and anxiety. Effects of anxiety reduction last longer from exercise compared to relaxation alone. Post-exercise reductions in state anxiety return to pre-exercise levels within 24 hours.

Green exercise, which is exercise in natural environments, known to provide physical and psychological health benefits, such as reducing stress and increased ability to cope with stress, reducing metal fatigue and improving concentration and cognitive function. Long-term exercise is usually associated with reductions in traits such as neuroticism and anxiety. Effects of anxiety reduction last longer from exercise compared to relaxation alone. Post-exercise reductions in state anxiety return to pre-exercise levels within 24 hours.

To reduce depression using fitness...

it is recommended to endure aerobic exercise (50-85% max HR) and anaerobic exercise (the greater the intensity the better) – 3-5x/week for 30-60 min, lasting at least 10 weeks although some changes have been seen after 5 weeks

to enhance mood using fitness...

it is recommended to endure rhythmic and repetitive exercise movements 20-30 min (moderate intensity) – 2-3 x/week. Aim to avoid competition – make it enjoyable. Rhythmic abdominal breathing in closed predictable activities has been shown to enhance mood.

to enhance self-esteem using fitness...

Focus on experiences of success, feelings of increased competence, and attaining your goals.

The Influence of Fitness on Wellness

Did you know?

Exercise has been consistently shown to positively influence feelings of well-being while decreasing stress, anxiety and depression. Reductions in depression do not depend on fitness levels, age, health, race, or socioeconomic status. The positive effects of physical activity on quality of life have been seen within 4 categories: enhanced physical functioning, subjective well-being, experiencing peak moments, and personal meaning. Exercise influences changes in sleep. In general, there is a small increase in total sleep time, although will all of the possible factors that affect sleep, everyone is different. Exercise increases self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-efficacy. Exercise over long periods of time is associated with moderate gains in cognitive functioning. Exercise has also been found to to enhance psychological well-being by means of: enhancing feelings of control, creating feelings of competency and self-efficacy, creating positive social interactions, leading to improved self-concept and self-esteem, and creating opportunities for fun and enjoyment.

Here are some guidelines for using exercise as therapy:

- 25% (1 out of 4) of the U.S. population experience anxiety within a lifetime

- 20% (1 out of 5) of the U.S. population experiences depression within a lifetime. Depression is estimated be the 2nd leading cause of death by 2020

- It is estimated that the global treatment coverage for depression and anxiety disorders is $147 billion (Chisholm et al., 2016)

Exercise has been consistently shown to positively influence feelings of well-being while decreasing stress, anxiety and depression. Reductions in depression do not depend on fitness levels, age, health, race, or socioeconomic status. The positive effects of physical activity on quality of life have been seen within 4 categories: enhanced physical functioning, subjective well-being, experiencing peak moments, and personal meaning. Exercise influences changes in sleep. In general, there is a small increase in total sleep time, although will all of the possible factors that affect sleep, everyone is different. Exercise increases self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-efficacy. Exercise over long periods of time is associated with moderate gains in cognitive functioning. Exercise has also been found to to enhance psychological well-being by means of: enhancing feelings of control, creating feelings of competency and self-efficacy, creating positive social interactions, leading to improved self-concept and self-esteem, and creating opportunities for fun and enjoyment.

Here are some guidelines for using exercise as therapy:

- Exercise should not be used in all cases of emotional disorders

- Explore the clients exercise history (good and bad experiences)

- Provide a precise diagnosis of the problem

- Use an individualized exercise prescription for volume

- Make exercise practical (e.g., biking to work, taking the stairs)

- Encourage exercise as an adjunct to other forms of therapy

- Develop a plan for any lack of adherence and irregular patterns of exercise

- Exercise therapy should only be done by qualified professionals

Regular Exercise is Essential

Individuals participating in resistance-training can increase muscular endurance, hypertrophy, strength and power. There is even a wider spectrum of health benefits from enduring and adhering to a resistance-training program, in conjunction with aerobic exercise. Ideally, adhering to a program of moderate-to-vigorous regular exercise should be a lifetime goal, however it is never too late to begin changing your life while improving your health and performance. Feel the benefits first hand, certainly you’ll be wanting more.

What exercise is best?

Regarding resistance training, it depends on your goal. Different muscular adaptations can be achieved by modifying the intensity, volume, and rest period between sets.

For Muscular Endurance:

-Low to moderate intensity (50-67% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-High volume (3-6 sets, > 12 repetitions)

-Rest time less than or equal to 30 seconds

For Muscular Hypertrophy:

-Low to moderate intensity (67-75% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-Moderate volume (3-6 sets, 6-12 repetitions)

-Rest time 30-90 seconds

For Basic Muscular Strength:

-High intensity (80-90% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-Moderate volume (3-5 sets, 4-8 repetitions)

-Rest time 2-5 minutes

For Muscular Power:

-High intensity (75-90% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-Low volume (3-5 sets, 2-5 repetitions)

-Rest time 2-5 minutes

Source: Baechle, Thomas R. & Roger Earle (Eds.). (2008) Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (3rd edition). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

For Muscular Endurance:

-Low to moderate intensity (50-67% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-High volume (3-6 sets, > 12 repetitions)

-Rest time less than or equal to 30 seconds

For Muscular Hypertrophy:

-Low to moderate intensity (67-75% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-Moderate volume (3-6 sets, 6-12 repetitions)

-Rest time 30-90 seconds

For Basic Muscular Strength:

-High intensity (80-90% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-Moderate volume (3-5 sets, 4-8 repetitions)

-Rest time 2-5 minutes

For Muscular Power:

-High intensity (75-90% 1 Repetition Maximum)

-Low volume (3-5 sets, 2-5 repetitions)

-Rest time 2-5 minutes

Source: Baechle, Thomas R. & Roger Earle (Eds.). (2008) Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (3rd edition). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

Can you exercise too much?

Absolutely. More is not always better. Over-training is a very serious and common phenomenon. Training too intensely and frequently with not enough recovery can put the body in a state of constant energy debt. This can result in a whole host of symptoms; similar symptoms are seen in individuals who do not train enough.

How often should i exercise?

According to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, "For substantial health benefits, adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity."

Source: https://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter4.aspx

Source: https://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter4.aspx

What is concurrent-training?

Concurrent training is aerobic exercise (running) combined with anaerobic exercise (resistance training). While it is commonly thought that aerobic exercise impairs strength gains seen in resistance training, appropriate timing of each exercise can exploit complementary training effects and minimize the compatibility problems associated with concurrent training. Simply put, there exists a balance to everything. The interference of adaptations depends on the the intensity, volume and frequency of training.

Source: Baechle, Thomas R. & Roger Earle (Eds.). (2008) Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (3rd edition). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

Source: Baechle, Thomas R. & Roger Earle (Eds.). (2008) Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (3rd edition). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

WHat is the law of initial values?

The law of initial values is a physiological principle

that is dependent on the initial baseline level. It states that with a given intensity of stimulation, the degree of change produced tends to be greater when the initial value is low. In other words, a novice exerciser will see results faster compared to an experienced exerciser.

that is dependent on the initial baseline level. It states that with a given intensity of stimulation, the degree of change produced tends to be greater when the initial value is low. In other words, a novice exerciser will see results faster compared to an experienced exerciser.

The Influence of Exercise on Bone

Bone is truly an extraordinary tissue as it can adapt and, in a sense, evolve to the forces in which it encounters. For example, the forces that occur when participating in physical activity results in a chain reaction of cell signaling that causes bone to grow. However, this process can work in the opposite direction in the lack of forces leading to the removal of bone. The chain reaction of cell signaling that occurs within bone is in of itself a phenomenal process that can be better explained. To dive deeper into the biomechanics of bone, click the button to explore how mechanical laws relate to the movement or structure of bone.

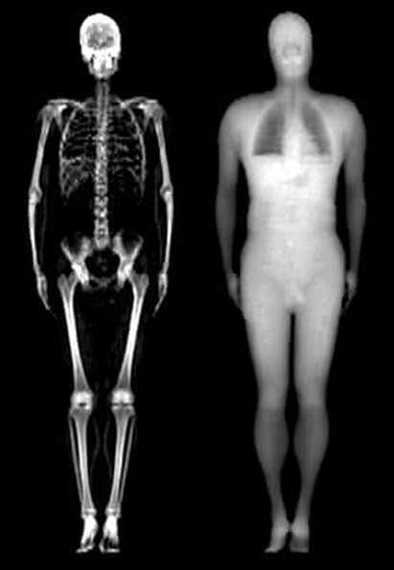

Density is measured by the quantity of mass per unit of volume. Therefore, bone mineral density (BMD) is the amount of minerals within the region of a bone, accounts for a large majority of the strength of bone. The strength of a bone is also determined by its size, shape, cortical thickness, cross-sectional area, and trabecular architecture. BMD, among other measures, can be assessed using DXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry), the "gold standard" technique that passes energy through an individual with high validity, reliability and ease of use. Overloading forces that are placed on bone enhance BMD and thus bone strength (Birch, MacLaren, & George, 2004).

|

Research on animals found that those who endured exercise resulted in a significant increase in cortical thickness and cross-sectional area, measures of increased bone strength (Woo et al., 1981). Most research states that mechanical stress from weight-bearing activities can enhance bone mass, formation and mechanical properties. Bone mass is higher in those who participate in activities that generate high impact forces compared to those participate in activities with low impact forces. However, if an individual does not meet nutritional recommendations, the effectiveness to increase bone mass diminishes. In addition, the rates of bone loss increase in the absence of mechanical forces. Research suggests both male and female adolescents that engage in resistance-training have a positively pronounced BMD compared to nonathletic adolescents (Kohrt, Bloomfield, Little, Nelson, & Yingling, 2004). Weight-bearing exercise among females athletes increases BMD and may prevent stress fractures and osteoporosis later in life (Mudd, Fornetti, & Pivarnik, 2007).

|

Many studies have concluded that weight-bearing exercise, such as resistance-training, can increase BMD, therefore increase bone strength, within adult athletes (Chilibeck, Sale, & Webber, 1995), within senior athletes (Leigey, Irrgang, Francis, Cohen, & Wright, 2009), among postmenopausal women (Kerr, Ackland, Maslen, Morton, & Prince, 2001), among heart transplant patients (Braith, Mills, Welsch, Keller, & Pollock, 1996) and people of all ages (Kohrt, Bloomfield, Little, Nelson, & Yingling, 2004).

The Influence of Exercise on Muscle

Muscle is similar to bone regarding the ability to adapt to physical forces. A resistance exercise program, being a weight-bearing activity, aids in the ability for muscle to increase endurance, size (hypertrophy), strength and power, depending on the stimulus. The adaptations that occur within the muscle vary between the exercises performed and the individuals that perform those exercises. Regular, dynamic exercise is recommended to observe progressive performance and maximum health benefits (Baechle & Earle, 2008).

References

Birch, K., MacLaren, D., & George, K. (2004). Instant notes in sport and exercise physiology. London: BIOS Scientific Publishers.

Baechle, T. R., & Earle, R. W. (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Braith, R. W., Mills, R. M., Welsch, M. A., Keller, J. W., & Pollock, M. L. (1996). Resistance exercise training restores bone mineral density in heart transplant recipients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 28(6), 1471–1477. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00347-6

Chilibeck, P., Sale, D., & Webber, C. (1995). Exercise and bone mineral density. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.)., 19(2), 103–22. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7747001

Chisholm, D., Sweeny, K., Sheehan, P., Rasmussen, B., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Saxena, S. (2016). Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 415–424. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30024-4

Hather, B. M., Tesch, P. A., Buchanan, P., & Dudley, G. A. (1991). Influence of eccentric actions on skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance training. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 143(2), 177–185. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09219.x

Hoffman, S. J. (Ed.). (2009). Introduction to Kinesiology with web study guide - 3rd edition: Studying physical activity (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Kerr, D., Ackland, T., Maslen, B., Morton, A., & Prince, R. (2001). Resistance training over 2 years increases bone mass in calcium-replete postmenopausal women. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research., 16(1), 175–81. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11149482

Kohrt, W. M., Bloomfield, S. A., Little, K. D., Nelson, M. E., & Yingling, V. R. (2004, November ). Physical activity and bone health: Medicine & science in sports & exercise. Retrieved December 6, 2016, from http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2004/11000/Physical_Activity_and_Bone_Health.24.aspx

Leigey, D., Irrgang, J., Francis, K., Cohen, P., & Wright, V. (2009). Participation in high-impact sports predicts bone mineral density in senior Olympic athletes. Sports Health, 1(6), 508–513. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445153/

Moritani, T., & de Vries, H. (1979). Neural factors versus hypertrophy in the time course of muscle strength gain. American journal of physical medicine., 58(3), 115–30. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/453338

Mudd, L. M., Fornetti, W., & Pivarnik, J. M. (2007). Bone mineral density in collegiate female athletes: Comparisons among sports. Jounral of Athletic Training, 42(3), 403–408. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1978462/

Pescatello, L. S., Arena, R., Riebe, D., & Thompson, P. D. (2013). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health.

Sale, D. (1988). Neural adaptation to resistance training. Medicine and science in sports and exercise., 20, . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3057313

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2014). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Champaign, IL, United States: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Willoughby, D., Stout, J., & Wilborn, C. (2006). Effects of resistance training and protein plus amino acid supplementation on muscle anabolism, mass, and strength. Amino acids., 32(4), 467–77. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16988909?dopt=Abstract

Woo, S. L., Kuei, S. C., Amiel, D., Gomez, M. A., Hayes, W. C., White, F. C., & Akeson, W. H. (1981). The effect of prolonged physical training on the properties of long bone: A study of Wolff’s law. Archive, 63(5), 780–787. Retrieved from http://jbjs.org/content/63/5/780.abstract

Baechle, T. R., & Earle, R. W. (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Braith, R. W., Mills, R. M., Welsch, M. A., Keller, J. W., & Pollock, M. L. (1996). Resistance exercise training restores bone mineral density in heart transplant recipients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 28(6), 1471–1477. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00347-6

Chilibeck, P., Sale, D., & Webber, C. (1995). Exercise and bone mineral density. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.)., 19(2), 103–22. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7747001

Chisholm, D., Sweeny, K., Sheehan, P., Rasmussen, B., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Saxena, S. (2016). Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 415–424. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30024-4

Hather, B. M., Tesch, P. A., Buchanan, P., & Dudley, G. A. (1991). Influence of eccentric actions on skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance training. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 143(2), 177–185. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09219.x

Hoffman, S. J. (Ed.). (2009). Introduction to Kinesiology with web study guide - 3rd edition: Studying physical activity (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Kerr, D., Ackland, T., Maslen, B., Morton, A., & Prince, R. (2001). Resistance training over 2 years increases bone mass in calcium-replete postmenopausal women. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research., 16(1), 175–81. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11149482

Kohrt, W. M., Bloomfield, S. A., Little, K. D., Nelson, M. E., & Yingling, V. R. (2004, November ). Physical activity and bone health: Medicine & science in sports & exercise. Retrieved December 6, 2016, from http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2004/11000/Physical_Activity_and_Bone_Health.24.aspx

Leigey, D., Irrgang, J., Francis, K., Cohen, P., & Wright, V. (2009). Participation in high-impact sports predicts bone mineral density in senior Olympic athletes. Sports Health, 1(6), 508–513. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445153/

Moritani, T., & de Vries, H. (1979). Neural factors versus hypertrophy in the time course of muscle strength gain. American journal of physical medicine., 58(3), 115–30. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/453338

Mudd, L. M., Fornetti, W., & Pivarnik, J. M. (2007). Bone mineral density in collegiate female athletes: Comparisons among sports. Jounral of Athletic Training, 42(3), 403–408. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1978462/

Pescatello, L. S., Arena, R., Riebe, D., & Thompson, P. D. (2013). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health.

Sale, D. (1988). Neural adaptation to resistance training. Medicine and science in sports and exercise., 20, . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3057313

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2014). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Champaign, IL, United States: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Willoughby, D., Stout, J., & Wilborn, C. (2006). Effects of resistance training and protein plus amino acid supplementation on muscle anabolism, mass, and strength. Amino acids., 32(4), 467–77. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16988909?dopt=Abstract

Woo, S. L., Kuei, S. C., Amiel, D., Gomez, M. A., Hayes, W. C., White, F. C., & Akeson, W. H. (1981). The effect of prolonged physical training on the properties of long bone: A study of Wolff’s law. Archive, 63(5), 780–787. Retrieved from http://jbjs.org/content/63/5/780.abstract