Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

|

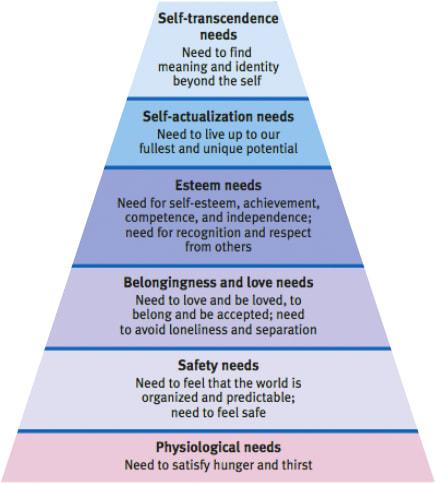

Some needs take priority over others. At this moment, with your needs for air and water hopefully satisfied, other motives—such as your desire to achieve —are energizing and directing your behavior. Let your need for water go unsatisfied and your thirst will preoccupy you. Deprived of air, your thirst would disappear.

Abraham Maslow described these priorities as a hierarchy of needs. At the base of this pyramid are our physiological needs, such as those for food and water. Only if these needs are met are we prompted to meet our need for safety, and then to satisfy the uniquely human needs to give and receive love and to enjoy self-esteem. Beyond this, said Maslow, lies the need to actualize one’s full potential. Near the end of his life, Maslow proposed that some people also reach a level of self-transcendence. At the self-actualization level, people seek to realize their own potential. |

At the self-transcendence level, people strive for meaning, purpose, and communion that is beyond the self, that is

transpersonal Maslow’s hierarchy is somewhat arbitrary; the order of such needs is not universally fixed. People have starved themselves to make a political statement. Nevertheless, the simple idea that some motives are more compelling than others provides a framework for thinking about motivation. In poorer nations that lack easy access to money and the food and shelter it buys, financial satisfaction more strongly predicts feelings of well-being. In wealthy nations, where most are able to meet basic needs, home-life satisfaction is a better predictor. Self-esteem matters most in individualist nations, whose citizens tend to focus more on personal achievements than on family and community identity.

transpersonal Maslow’s hierarchy is somewhat arbitrary; the order of such needs is not universally fixed. People have starved themselves to make a political statement. Nevertheless, the simple idea that some motives are more compelling than others provides a framework for thinking about motivation. In poorer nations that lack easy access to money and the food and shelter it buys, financial satisfaction more strongly predicts feelings of well-being. In wealthy nations, where most are able to meet basic needs, home-life satisfaction is a better predictor. Self-esteem matters most in individualist nations, whose citizens tend to focus more on personal achievements than on family and community identity.

Absolute and Relative Poverty

There exists no "objective" operational definition of poverty. There cannot be. States of well-being or “ill-being” are essentially personal and depend on the individual’s preferences, expectations, self image—characteristics which are in turn determined by some mysterious mix of biology and environment. For each person the condition of poverty will lie somewhere on the continuum of well-being. The location will be quite unique for each individual and at different stages of life for the same individual. Poverty is an eminently subjective state and any precise definition for the purpose of measuring poverty will necessarily be subjective

Given this, the standard distinction in the literature is between absolute and relative definitions of poverty. The former approach focuses on the lack of basic necessities while the latter emphasizes inadequacy compared to

average living standards. There is a sense in which the distinction is artificial. Any operational definition must be relative because what is considered to be a necessity depends to some extent on the conditions in the larger society in which one is a member. Yet at the same time there seems to be an irreducible core of necessities invariant through time. An individual or family lacking water, food, shelter and clothing would have been poor at the time of Plato or in the late 20th century. What is absolute (or nearly so) about the absolute approach is the items included in the list of necessities. What is relative about the absolute approach is the quantity and quality of each included item. Therefore, while all operational definitions of poverty are, to some extent at least, relative, it is fair to say that conventionally the term absolute poverty conveys a sense of the lack of all the basic physical necessities, whereas, the term relative poverty conveys the impression of a lack of both physical and ‘social’ needs.

Given this, the standard distinction in the literature is between absolute and relative definitions of poverty. The former approach focuses on the lack of basic necessities while the latter emphasizes inadequacy compared to

average living standards. There is a sense in which the distinction is artificial. Any operational definition must be relative because what is considered to be a necessity depends to some extent on the conditions in the larger society in which one is a member. Yet at the same time there seems to be an irreducible core of necessities invariant through time. An individual or family lacking water, food, shelter and clothing would have been poor at the time of Plato or in the late 20th century. What is absolute (or nearly so) about the absolute approach is the items included in the list of necessities. What is relative about the absolute approach is the quantity and quality of each included item. Therefore, while all operational definitions of poverty are, to some extent at least, relative, it is fair to say that conventionally the term absolute poverty conveys a sense of the lack of all the basic physical necessities, whereas, the term relative poverty conveys the impression of a lack of both physical and ‘social’ needs.

Basic Human Needs

Our bodies are incredible machines capable of much more than we give them credit for. But just like any machine, it needs to be taken care of. There are 5 basic needs our bodies require to survive:

- Air - Oxygen in one of the most essential human needs. Our bodies need a consistent supply of it to function properly. Without access to oxygen, you can experience a condition know as cerebral hypoxia which affects our brains. As little as 5 min without air can result in brain damage, and after 15 minutes, the brain damage can be so severe that most people will not recover. This is the body’s greatest need.

- Water - Apart form air, water is the most essential element to life. Our bodies are made up of 70% water, and as we live we deplete our body’s resources, which is why it is so important to stay hydrated. The dehydration process begins when the body is unable to maintain hydration balance. A 2.5% loss in water volume in a person leads to a 25% reduction in blood volume. This means the blood gets thicker and the heart has to work harder to pump nutrients throughout the body. This lower blood volume also reduces flow to the extremities, leading to numbness in the fingers and toes. At this point, the blood is too thick to make its way through the small capillaries in the brain, this makes it impossible to concentrate or focus for any period of time.

- Food - The body can survive quite a while without food. At first it uses up energy found in its fat and glycogen reserves. Once the fat reserves are used up, the body will begin breaking down the musculature into proteins for energy. Muscles break down quickly, within one week. Once this process has completed the body has no more internal energy sources to draw from and dies. Most people who suffer from starvation don’t die directly from it. At this stage, the body is very susceptible to infectious diseases, and it is the infections that end up killing them.

- Shelter - A shelter, which could include appropriate clothing, has the purpose of protecting you from the elements, keeping your body at a consistent temperature. The biggest concern with being exposed to the elements is water loss. Cold temperatures and wind can strip away valuable moisture just as quickly as high temperatures can cause sweat related loss. When we are unable to maintain a constant temperature, we run the risk of hypothermia or heat stroke. With hypothermia, the body loses the ability to control internal temperatures. With heat stroke, the central nervous system starts to break down and the brain overheats and dies.

- Sleep - Sleep deprivation has long been underestimated as a necessity for survival, but a severe lack of sleep can be detrimental to your health and your life. Problems can range from decreased body temperature to cognitive impairment and hallucination. Although the mechanisms of sleep are not well understood, the side effects of a lack of sleep are. Headaches can begin as soon as 24 hours after missing sleep. 72 hours in, memory is impaired and reality becomes distorted. At this point driving becomes very dangerous. After 96 hours without sleep, cognition is markedly impaired. After 144 hours, hallucinations begin, you are unable to concentrate or preform tasks. This lack of clear thinking can be life threatening.

- Sanitation - Proper means for the removal of human waste helps protect from deadly toxins and pathogens and is critical in promoting human survival.

- Space - As humans, we require personal space. In addition to the requirement for shelter, or suitable indoor living space, humans need outdoor space, to avoid overcrowding and chaos.

- Connectivity - As humans have evolved to interact in community settings, both hunting and gathering in groups, touch—as in a caress—is often considered a basic human survival need. In fact, empirical evidence has shown that touch is essential for the early growth and development of healthy humans.

Separate Your Needs From Your Wants

As aforementioned, believe it or not, there are not many needs that humans require to live - water, food, shelter, sleep, sanitation, space, and connection. All of the other miscellaneous items that people consume are not necessary, but are none the less consumed. Often times, through the work of cleaver advertising, people are convinced that they need to consume products beyond their basic needs. Consequently, people struggle to get by due to the mindless allocation of precious resources on excess goods and services.

References

Myers, D., College, H. and Michigan, H. (2010). Psychology. 9th ed. New York: Worth Publishers.

Sarlo, C. (1996). Poverty in Canada. Vancouver, B.C., Canada: Fraser Institute.

Sarlo, C. (1996). Poverty in Canada. Vancouver, B.C., Canada: Fraser Institute.