Step 3: Eat Plant-Based

|

What is a Plant-based Diet?

A person following a "plant based diet" eats only plant foods (or mostly plant foods). Unless the person tells you otherwise, assume they only eat plants and never eat animal-based foods or products. Most people who identify as eating a "plant based diet" focus on eating the whole plant, rather than segments, or a minimally processed version of it. Technically, mushrooms and yeast aren't "plants" since they belong to the Fungi Kingdom, but these foods are eaten by vegans and people who follow a "plant-based diet".

What Vegetables are Best?

The benefits from vegetable consumption may vary between certain groups of vegetables. Researchers have observed a significant inverse association with various cancers [bladder cancer (Michaud et al., 1999) and prostate cancer (Kirsh et al., 2007)] and the consumption of cruciferous vegetables, compared to total vegetable consumption.

Cruciferous vegetables are just one of the many groups of vegetables that are beneficial to human health. Ideally it is best to consume a variety of foods as no single food can provide all the nutrients, in the proper amounts, for optimal health.

Influence on Health

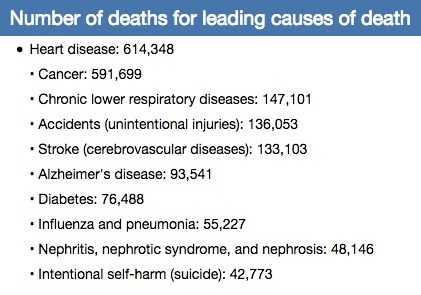

Among the leading causes of death in the United States, chronic degenerative diseases such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes may be prevented with a change in diet. Researchers continue to uncover what has long been known, that consuming a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds promotes optimal health. Consuming a balance of plant-based foods that are nutrient-dense, rather than energy dense can significantly reduce morbidity and ultimately mortality.

|

Influence on Inflammation

Researchers have observed a significant inverse association between inflammation and the consumption of cruciferous vegetables within studies conducted on animals. More recently, researchers evaluated the association between circulating levels of inflammation and the consumption of cruciferous vegetables in humans.

Participants that were analyzed included over 1000 females from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS). A baseline survey and questionnaire was conducted to obtain data on anthropometric measurements, demographics, diet intake, lifestyle habits, medical history and other characteristics. In addition, biospecimens were collected to measure inflammatory [tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF- α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-6] and oxidative stress [F2-isoprostanes (F2-IsoP); 2,3-dinor-5,6-dihydro-15-F2t-IsoP (F2-IsoP-M)] markers, from blood and urine, respectively.

Dietary intake was assessed using the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), which has been indicated to be a valid and reproducible measure of food group intake. Vegetable groups included cruciferous vegetables (kale, collard greens, cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and bok choy), green leafy vegetables, allium vegetables (garlic, garlic sprouts, onions) and legumes. Participants were asked how often (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly, yearly or never), on average, they had consumed a specific food group.

The researchers discovered that a higher intake of cruciferous vegetables was associated with significantly lower circulating concentrations of proinflammatory markers. A similar, but less evident, inverse association was observed with the intake of all vegetables combined but not with noncruciferous vegetables. No statistically significant association was observed between oxidative stress markers and intake of vegetables, a phenomenon seen in many epidemiological studies. These results accounted for potential confounding variables such as socioeconomic status, dietary and nondietary lifestyle factors, BMI, health conditions and medication use. The evidence provided in this study supports the recommendation to increase consumption of cruciferous vegetables to reduce levels of inflammation.

Heart Disease

Researchers have evaluated the association between consumption of cruciferous vegetables and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Data was analyzed from 2 studies conducted in China – the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS) and the Shanghai Men’s Health Study (SMHS). Participants that were analyzed in the SWHS included over 73,000 women between the ages of 40-70 years from 7 urban communities in Shanghai. Participants that were analyzed in the SMHS included over 61,000 men between the ages of 40-74 years from the same communities. Data on anthropometric measurements, demographics, diet, lifestyle habits, medical history and other factors was obtained via interviews.

Similar to the methods of Dietary intake was assessed using the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), which has been indicated to be a valid and reproducible measure of food group intake. Vegetable groups included cruciferous vegetables, green leafy vegetables, allium vegetables and legumes. Participants were asked how often, on average, that he or she had consumed a specific food group.

Participants were followed via home visits and records from several registries to analyze deaths from all causes. Information on death certificates was used to determine the cause of death, a valid method of measuring rates of CVD and cancer.

In both men and women, individuals with a higher total fruit and vegetable consumption tended to be younger with higher education, occupational status and family income, as well as a a higher frequency of exercise. Of the identified deaths between the groups, fruit and vegetable consumption, especially cruciferous vegetable consumption, was inversely associated with risk of total mortality. Compared to total mortality, a stronger inverse relationship was observed between the risk of CVD mortality, in both men and women, and the consumption of total vegetables, especially cruciferous vegetables. Cruciferous vegetables are uniquely characterized by their high content of glucosinolates. Glucosinolates are sulfur-containing compounds that are suggested to provide anti-inflammatory effects and protection against certain cancers.

These findings support the recommendation to increase consumption of fruits and vegetables, particularly cruciferous vegetables, to promote cardiovascular health and overall longevity.

Data was analyzed from 2 studies conducted in China – the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS) and the Shanghai Men’s Health Study (SMHS). Participants that were analyzed in the SWHS included over 73,000 women between the ages of 40-70 years from 7 urban communities in Shanghai. Participants that were analyzed in the SMHS included over 61,000 men between the ages of 40-74 years from the same communities. Data on anthropometric measurements, demographics, diet, lifestyle habits, medical history and other factors was obtained via interviews.

Similar to the methods of Dietary intake was assessed using the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), which has been indicated to be a valid and reproducible measure of food group intake. Vegetable groups included cruciferous vegetables, green leafy vegetables, allium vegetables and legumes. Participants were asked how often, on average, that he or she had consumed a specific food group.

Participants were followed via home visits and records from several registries to analyze deaths from all causes. Information on death certificates was used to determine the cause of death, a valid method of measuring rates of CVD and cancer.

In both men and women, individuals with a higher total fruit and vegetable consumption tended to be younger with higher education, occupational status and family income, as well as a a higher frequency of exercise. Of the identified deaths between the groups, fruit and vegetable consumption, especially cruciferous vegetable consumption, was inversely associated with risk of total mortality. Compared to total mortality, a stronger inverse relationship was observed between the risk of CVD mortality, in both men and women, and the consumption of total vegetables, especially cruciferous vegetables. Cruciferous vegetables are uniquely characterized by their high content of glucosinolates. Glucosinolates are sulfur-containing compounds that are suggested to provide anti-inflammatory effects and protection against certain cancers.

These findings support the recommendation to increase consumption of fruits and vegetables, particularly cruciferous vegetables, to promote cardiovascular health and overall longevity.

References

Jiang, Y., Wu, S., Shu, X., Xiang, Y., Ji, B., Milne, G., … Yang, G. (2014). Cruciferous vegetable intake is inversely correlated with circulating levels of proinflammatory markers in women. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics., 114(5), 700–8. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24630682

Kirsh, V., Peters, U., Mayne, S., Subar, A., Chatterjee, N., Johnson, C., … Prostate (2007). Prospective study of fruit and vegetable intake and risk of prostate cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute., 99(15), 1200–9. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17652276

Michaud, D., Spiegelman, D., Clinton, S., Rimm, E., Willett, W., & Giovannucci, E. (1999). Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of bladder cancer in a male prospective cohort. Journal of the National Cancer Institute., 91(7), 605–13. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10203279

Zhang, X., Shu, X.-O., Xiang, Y.-B., Yang, G., Li, H., Gao, J., … Zheng, W. (2011). Cruciferous vegetable consumption is associated with a reduced risk of total and cardiovascular disease mortality. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(1), 240–246. http://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.009340

Kirsh, V., Peters, U., Mayne, S., Subar, A., Chatterjee, N., Johnson, C., … Prostate (2007). Prospective study of fruit and vegetable intake and risk of prostate cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute., 99(15), 1200–9. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17652276

Michaud, D., Spiegelman, D., Clinton, S., Rimm, E., Willett, W., & Giovannucci, E. (1999). Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of bladder cancer in a male prospective cohort. Journal of the National Cancer Institute., 91(7), 605–13. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10203279

Zhang, X., Shu, X.-O., Xiang, Y.-B., Yang, G., Li, H., Gao, J., … Zheng, W. (2011). Cruciferous vegetable consumption is associated with a reduced risk of total and cardiovascular disease mortality. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(1), 240–246. http://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.009340