Personality Structure

|

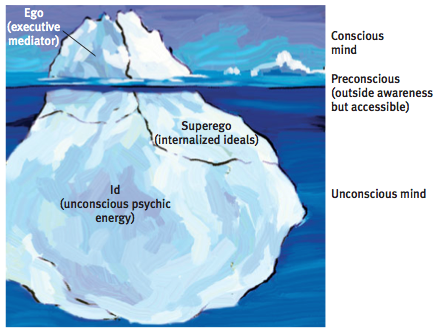

According to Sigmund Freud, human personality—including its emotions and strivings—arises from a conflict between impulse and restraint—between our aggressive, pleasure-seeking biological urges and our internalized social controls over these urges. Freud believed personality is the result of our efforts to resolve this basic conflict—to express these impulses in ways that bring satisfaction without also bringing guilt or punishment. To understand the mind’s dynamics during this conflict, Freud proposed three interacting systems: the id, ego, and superego. The mind is mostly hidden beneath the conscious surface. Note that the id is totally unconscious, but ego and superego operate both consciously and unconsciously. Unlike the parts of a frozen iceberg, however, the id, ego, and superego interact.

|

The id’s unconscious psychic energy constantly strives to satisfy basic drives to survive, reproduce, and aggress. The id operates on the pleasure principle: It seeks immediate gratification. To envision an id-dominated person, think of a newborn infant crying out for satisfaction, caring nothing for the outside world’s conditions and demands. Or think of people with a present rather than future time perspective—those who often use tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs, and would sooner party now than sacrifice today’s pleasure for future success and happiness (Keough et al., 1999).

As the ego develops, the young child responds to the real world. The ego, operating on the reality principle, seeks to gratify the id’s impulses in realistic ways that will bring long-term pleasure. (Imagine what would happen if, lacking an ego, we ex- pressed all our unrestrained sexual or aggressive impulses.) The ego contains our partly conscious perceptions, thoughts, judgments, and memories.

Around age 4 or 5, Freud theorized, a child’s ego recognizes the demands of the newly emerging superego, the voice of our moral compass (conscience) that forces the ego to consider not only the real but the ideal. The superego focuses on how we ought to behave. It strives for perfection, judging actions and producing positive feelings of pride or negative feelings of guilt. Someone with an exceptionally strong superego may be virtuous yet guilt-ridden; another with a weak superego may be wantonly self-indulgent and remorseless.

As the ego develops, the young child responds to the real world. The ego, operating on the reality principle, seeks to gratify the id’s impulses in realistic ways that will bring long-term pleasure. (Imagine what would happen if, lacking an ego, we ex- pressed all our unrestrained sexual or aggressive impulses.) The ego contains our partly conscious perceptions, thoughts, judgments, and memories.

Around age 4 or 5, Freud theorized, a child’s ego recognizes the demands of the newly emerging superego, the voice of our moral compass (conscience) that forces the ego to consider not only the real but the ideal. The superego focuses on how we ought to behave. It strives for perfection, judging actions and producing positive feelings of pride or negative feelings of guilt. Someone with an exceptionally strong superego may be virtuous yet guilt-ridden; another with a weak superego may be wantonly self-indulgent and remorseless.

"The most strongly enforced of all known taboos

is the taboo against knowing who or what you really are

behind the mask of your apparently separate,

independent, and isolated ego."

Alan Watts

References

Keough, K, Zimbardo, P, & Boyd, J. (1999). Who’s smoking, drinking, and using drugs? Time perspective as a predictor of substance use. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 2, 149–164. (p. 555)

Myers, D. (2010). Psychology. 9th ed. New York: Worth Publishers.

Myers, D. (2010). Psychology. 9th ed. New York: Worth Publishers.