What are Carbohydrates?

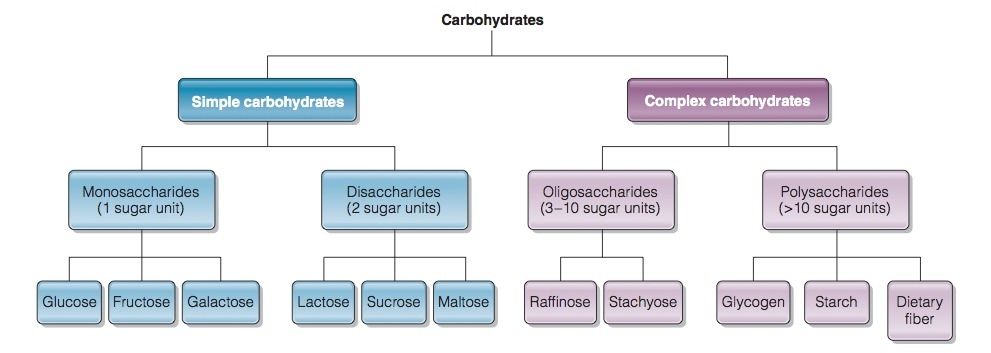

Carbohydrates consist of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms and play many roles in the body. There are several types of carbohydrates.

Simple carbohydrates, also known as monosaccharide, consist of a single sugar molecule. The most common monosaccharides are glucose, fructose and galactose. A carbohydrate consisting of two sugar molecules is a disaccharide. The most common disaccharides are lactose (galactose and glucose), maltose (glucose and glucose) and sucrose (fructose and glucose).

Complex carbohydrates contain many monosaccharides. Glycogen is a polysaccharide that consists of many glucose molecules, and is found primarily in the liver and skeletal muscle. Starch is a polysaccharide that plants store. Fiber refers to a group of diverse plant polysaccharides that cannot be digested in the small intestine. Bacteria break down fiber, producing gas, fats and other beneficial substances. Fiber is crucial for the growth of intestinal bacterial which help fight pathogenic bacteria (McGuire, Beerman, & William, 2011)

Simple carbohydrates, also known as monosaccharide, consist of a single sugar molecule. The most common monosaccharides are glucose, fructose and galactose. A carbohydrate consisting of two sugar molecules is a disaccharide. The most common disaccharides are lactose (galactose and glucose), maltose (glucose and glucose) and sucrose (fructose and glucose).

Complex carbohydrates contain many monosaccharides. Glycogen is a polysaccharide that consists of many glucose molecules, and is found primarily in the liver and skeletal muscle. Starch is a polysaccharide that plants store. Fiber refers to a group of diverse plant polysaccharides that cannot be digested in the small intestine. Bacteria break down fiber, producing gas, fats and other beneficial substances. Fiber is crucial for the growth of intestinal bacterial which help fight pathogenic bacteria (McGuire, Beerman, & William, 2011)

Sugar is Sugar is Sugar

|

Agave nectar

Barbados sugar Barley malt Barley malt syrup Beet sugar Brown sugar Buttered syrup Cane juice Cane juice crystals Cane sugar Caramel Carob syrup Castor sugar Coconut palm sugar Coconut sugar Confectioner’s sugar Corn sweetener Corn syrup Corn syrup solids Date sugar |

Dehydrated cane juice

Demerara sugar Dextrin Dextrose Evaporated cane juice Free-flowing brown sugars Fructose Fruit juice Fruit juice concentrate Glucose Glucose solids Golden sugar Golden syrup Grape sugar HFCS (high-fructose corn syrup) Honey Icing sugar Invert sugar Malt syrup Maltodextrin Maltol |

Maltose

Mannose Maple syrup Molasses Muscovado Palm sugar Panocha Powdered sugar Raw sugar Refiner’s syrup Rice syrup Saccharose Sorghum syrup Sucrose Sugar (granulated) Sweet sorghum Syrup Treacle Turbinadosugar Yellow sugar |

There are over 60 different names for sugar, but they are all sugar, regardless of the name. Be aware of these ingredients when purchasing products, and know that there is added sugar, even if you do not see the word "sugar".

Carbohydrate Requirements

Technically, carbohydrates are not essential nutrients; in other words, sugar has no nutritional value except for calories and, thus, may have negative health implications for those at risk of overweight. However, carbohydrates are important in providing dietary fiber and energy. The nervous system and red blood cells rely almost exclusively on glucose for energy. Although the type of carbohydrate makes all the difference. It is important to eat a variety of brightly colored vegetables (dark green, red, and orange), which contain complex carbohydrates. Whole, unrefined grain foods should replace refined grains, (McGuire, Beerman, & William, 2011) since the consumption of refined carbohydrates has been observed to lead to low-grade, chronic inflammation in the body, which contributes to a wide variety of degenerative diseases including osteoporosis (Tucker, 2014). Diets high in refined carbohydrates and processed foods, such as crackers, cereals, breads, pastas, sugar-sweetened beverages (sodas), sports drinks (e.g., Gatorade), and grain-based desserts have consistently shown to drastically impair bone growth and strength (Tjäderhane & Larmas, 1998) and bone mineral density. In addition, sugar-sweetened beverages, such as sodas have been shown to reduce the consumption of nutrient-dense fluids (Lorincz, Manske, & Zernicke, 2009).

|

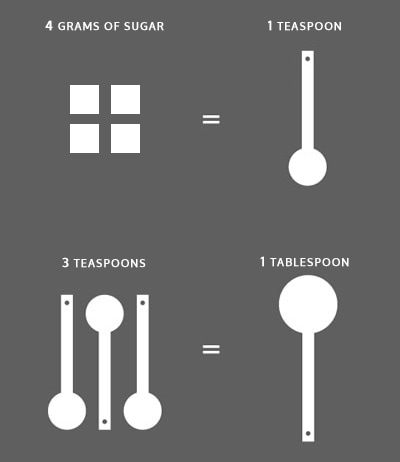

The Institute of Medicine suggests an Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) of 45 to 65% of total energy from carbohydrates. The 2015 dietary guidelines for Americans recommends no more than 10% of total calories is in the form of added sugar. If you may have noticed, unlike sodium of fat, sugar does not have a daily reference value. However, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends no more than 9 teaspoons (38 grams) of added sugar per day for men, and 6 teaspoons (25 grams) per day for women.

Carbohydrates

45-65% of total calories Added Sugar <10% of total calories |

The Nemesis to Optimal Health

When you eat sugar, it turns into glucose in your blood. When your body notices that your glucose levels are high, it produces insulin via the pancreas. Insulin, in turn, is released into the body to store the glucose that is sitting in your blood not being burned up. The more sugar, or glucose, you take in, the more insulin your body will produce and release. Insulin stores the glucose in the form of glycogen in your liver and muscles, and when that limited storage is full, insulin will help turn the sugar energy into fat.

Unfortunately, insulin can have harmful effects. Insulin can inflame all the cells it comes into contact with. This inflammation is not only the beginning of aging, but also inflammatory conditions including cancer and other degenerative illnesses.

Researchers have demonstrated a connection between sugar (and other foods that register in the body with a high glycemic index, like white flour and processed starches) and cancer, especially those who already have an underlying degree of insulin resistance (Schernhammer, 2005). Normally, insulin escorts glucose from the bloodstream into the cells of the body, akin to a key opening a lock. In some individuals, the cells of the body are more resistant to insulin's action. Similar results have been observed in a studies on colon cancer, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer (Slattery et al., 1997; Jenkins et al., 2002; Bosetti et al., 2001)

The over-consumption of added sugars—whether in the form of high-fructose corn syrup, fructose, glucose, dextrose, or the sucrose from sugarcane and sugar beets—is one of the major health problems facing our nation today. For just an idea of the possible health effects of excess sugar consumption, consider that sugar has been cited as a contributing factor to:

Unfortunately, insulin can have harmful effects. Insulin can inflame all the cells it comes into contact with. This inflammation is not only the beginning of aging, but also inflammatory conditions including cancer and other degenerative illnesses.

Researchers have demonstrated a connection between sugar (and other foods that register in the body with a high glycemic index, like white flour and processed starches) and cancer, especially those who already have an underlying degree of insulin resistance (Schernhammer, 2005). Normally, insulin escorts glucose from the bloodstream into the cells of the body, akin to a key opening a lock. In some individuals, the cells of the body are more resistant to insulin's action. Similar results have been observed in a studies on colon cancer, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer (Slattery et al., 1997; Jenkins et al., 2002; Bosetti et al., 2001)

The over-consumption of added sugars—whether in the form of high-fructose corn syrup, fructose, glucose, dextrose, or the sucrose from sugarcane and sugar beets—is one of the major health problems facing our nation today. For just an idea of the possible health effects of excess sugar consumption, consider that sugar has been cited as a contributing factor to:

- Overweight and obesity

- Immune system suppression, inviting infection and disease

- Premature aging

- Cancer of the breast, ovaries, prostate, and rectum

- Decreased absorption of calcium and magnesium

- Diabetes

- Fatigue

- Decreased energy and reduced ability to build muscle

- Heart disease

- Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

- Osteoporosis

- Yeast infections and overgrowth

- Depression

- Dental decay and gum disease

- Hormone imbalance

- Auto immune disorders such as arthritis, allergies, asthma, psoriasis, eczema, and fibromyalgia

- Absentmindedness, poor long- and short-term memory, learning disorders, erratic, disruptive behavior, difficulty concentrating, and decreased learning capacity in both adults and children

Sugar Substitutes

Sugar substitutes such as saccharin (Sweet-N-Low), sucralose (Splenda) and aspartame (Equal and Nutrasweet) should be avoided all together. Their negative health effects can easily exceed the sugars they are replacing. Evidence suggests that aspartame might cause altered brain function and behavior changes. The FDA has also been overwhelmed with consumer complaints about aspartame, including symptoms of fibromyalgia, multiple sclerosis symptoms, dizziness, headaches, and menstrual problems.

It is also advised to avoid sucralose, an alternative sugar substitute. Few human studies have been published regarding the safety of sucralose. Researchers have observed that sucralose was shown to cause a decrease in the size of thymus glands, to cause liver and kidney enlargement, reduce growth rate, decrease red blood cell count, and decrease placenta and fetal body weights, in animals. Sucralose also has the potential to introduce pesticides, heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, and more into the body. Finally, there is no clear evidence that sucralose—or any artificial sweetener—is useful to lose weight. In fact, evidence suggests that these substances may actually stimulate your appetite, causing increased weight gain (Mercola, 2005).

It is also advised to avoid sucralose, an alternative sugar substitute. Few human studies have been published regarding the safety of sucralose. Researchers have observed that sucralose was shown to cause a decrease in the size of thymus glands, to cause liver and kidney enlargement, reduce growth rate, decrease red blood cell count, and decrease placenta and fetal body weights, in animals. Sucralose also has the potential to introduce pesticides, heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, and more into the body. Finally, there is no clear evidence that sucralose—or any artificial sweetener—is useful to lose weight. In fact, evidence suggests that these substances may actually stimulate your appetite, causing increased weight gain (Mercola, 2005).

Sugar is Addicting

In our modern civilization, we are constantly bombarded with food-like products that are filled with various forms of refined sugars. It is well established that the overconsumption of diets that are rich in sugars contributes, with other factors, to the current obesity epidemic. The overconsumption of energy-dense foods or beverages is initially motivated by the pleasure of taste and can be compared to drug addiction. In fact, there are many biological similarities between diets high in sugar and individuals that abuse drugs.

Sugar is physically addictive. Researchers have observed this phenomena in a simple experiment conducted on rats. When rats are given a mutually-exclusive choice between water sweetened with saccharin (an intense calorie-free sweetener) and cocaine (a highly addictive and harmful substance), 94% of the animals chose the sugar-sweetened water. The same results were also observed with sucrose. These results clearly demonstrate that sugar can surpass cocaine reward, even in drug-sensitized and -addicted individuals. The researchers speculate that the addictive potential of intense sweetness results from taste receptors that evolved over time, from environments low in sugar. This observed overstimulation of these receptors from diets rich in sugar, commonly seen in many modern societies, generate a extraordinary reward signal in the brain - leading to the potential to override self-control mechanisms and ultimately leading to addiction (Lenoir, Serre, Cantin, & Ahmed, 2007).

Sugar causes your energy receptors to become overwrought, and in a sense, deadened, so that you ay not feel energized by anything but sugar. If you're eating too much sugar, you can feel lethargic and slow after consuming other foods, a low that makes your physical craving for the pick-me-up of sugar even more intense. This is how a physical addiction operates. You experience a roller coaster of energetic ups and downs, with the lows slowly growing longer, and the highs shrinking steadily, until the consumption of sugar brings on only fatigue, as does the consumption of any other food.

For many, sugar is an legitimate addiction, similar to cigarette dependency. Consuming excess quantities of sugar affect health as severely as cigarettes do, if not more so. The solution is to overcome the sugar addiction. Fortunately, by adopting this concept, consuming the foods your body was designed to eat and utilizing tools to overcome emotional barriers, you won’t have to “fight” the craving, because it will naturally disappear overtime.

Sugar is physically addictive. Researchers have observed this phenomena in a simple experiment conducted on rats. When rats are given a mutually-exclusive choice between water sweetened with saccharin (an intense calorie-free sweetener) and cocaine (a highly addictive and harmful substance), 94% of the animals chose the sugar-sweetened water. The same results were also observed with sucrose. These results clearly demonstrate that sugar can surpass cocaine reward, even in drug-sensitized and -addicted individuals. The researchers speculate that the addictive potential of intense sweetness results from taste receptors that evolved over time, from environments low in sugar. This observed overstimulation of these receptors from diets rich in sugar, commonly seen in many modern societies, generate a extraordinary reward signal in the brain - leading to the potential to override self-control mechanisms and ultimately leading to addiction (Lenoir, Serre, Cantin, & Ahmed, 2007).

Sugar causes your energy receptors to become overwrought, and in a sense, deadened, so that you ay not feel energized by anything but sugar. If you're eating too much sugar, you can feel lethargic and slow after consuming other foods, a low that makes your physical craving for the pick-me-up of sugar even more intense. This is how a physical addiction operates. You experience a roller coaster of energetic ups and downs, with the lows slowly growing longer, and the highs shrinking steadily, until the consumption of sugar brings on only fatigue, as does the consumption of any other food.

For many, sugar is an legitimate addiction, similar to cigarette dependency. Consuming excess quantities of sugar affect health as severely as cigarettes do, if not more so. The solution is to overcome the sugar addiction. Fortunately, by adopting this concept, consuming the foods your body was designed to eat and utilizing tools to overcome emotional barriers, you won’t have to “fight” the craving, because it will naturally disappear overtime.

Candida Overgrowth

Candida albicans (a species of yeast) naturally occurs in the human body, but can grow disproportionately, causing excess infections and other problems. This culture thrives on the consumption of sugar and yeast, so giving up yeast as you abstain from sugar will help alleviate candida-realted issues (including gas, irritable bowel syndrome, heartburn, bad breath, headaches, congestion, dry or itchy skin, anxiety, fluid retention, and frequent urination).

The Sugar Industry Influences Dietary Recommendations

Research stretching over decades has continuously suggested that excess sugar damages health, although the sugar industry has successfully misinformed the public with pseudoscience. Researchers have discovered internal documents that suggest the sugar industry muffled research indicating a significant relationship between sugar and adverse health effects including, heart disease and cancer (Kearns, Apollonio & Glantz, 2017). And this isn't the first time the sugar industry has been caught in the act. Researchers uncovered evidence suggesting the sugar industry systematically misrepresented research linking sugar to cancer, obesity, and heart disease (Kearns, Schmidt and Glantz, 2016). By simply eliminating refined carbohydrates, one's overall health can be drastically improved in many ways.

References

Bosetti, C., Negri, E., Franceschi, S., Pelucchi, C., Talamini, R., Montella, M., Conti, E. and La Vecchia, C. (2001). Diet and ovarian cancer risk: A case-control study in Italy. International Journal of Cancer, 93(6), pp.911-915. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.1422

Jenkins, D., Kendall, C., Augustin, L., Franceschi, S., Hamidi, M., Marchie, A., Jenkins, A. and Axelsen, M. (2002). Glycemic index: overview of implications in health and disease. American Society of Clincal Nutrition, 76, pp.266S-73S. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/76/1/266S.full.pdf+html

Johnson, R.K., Appel, L., Brands, M., Howard, B., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R., Sacks, F., Steffen, L., & Wyllie-Rosett, J. (2009, September 15). Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation , 120(11), 1011-20. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627. Retrieved from http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/120/11/1011.full.pdf

Kearns, C., Apollonio, D. and Glantz, S. (2017). Sugar industry sponsorship of germ-free rodent studies linking sucrose to hyperlipidemia and cancer: An historical analysis of internal documents. PLOS Biology, 15(11), p.e2003460. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2003460

Kearns, C., Schmidt, L. and Glantz, S. (2016). Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(11), p.1680. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394

Lenoir, M., Serre, F., Cantin, L., & Ahmed, S. (2007). Intense Sweetness Surpasses Cocaine Reward. Plos ONE, 2(8), e698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000698

Lorincz, C., Manske, S. L., & Zernicke, R. (2009). Bone health. , 1(3), . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445243/

McGuire, M., Beerman, K. A., & William, M. (2011). Nutritional sciences: From fundamentals to food (with table of food composition booklet) (3rd ed.). Boston, MA, United States: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Mercola, J. (2005). Dr. Mercola's total health program. Schaumburg, IL: Mercola.com.

Schernhammer, E., Hu, F., Giovannucci, E., Michaud, D., Colditz, G., Stampfer, M. and Fuchs, C. (2005). Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drink Consumption and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in Two Prospective Cohorts. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 14(9), pp.2098-2105. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0059

Slattery, M., Benson, J., Berry, D., Duncan, D., Edwards, S., Caan, B. and Potter, J. (1997). Dietary sugar and colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 6, pp.677-685. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/cebp/6/9/677.full.pdf

Tjäderhane, L., & Larmas, M. (1998). A high sucrose diet decreases the mechanical strength of bones in growing rats. The Journal of nutrition., 128(10), 1807–10. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9772153

Tucker, K. L. (2014). Vegetarian diets and bone status. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(Supplement_1), 329S–335S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071621

U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th Edition ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; . Accessed March 8, 2016.

Jenkins, D., Kendall, C., Augustin, L., Franceschi, S., Hamidi, M., Marchie, A., Jenkins, A. and Axelsen, M. (2002). Glycemic index: overview of implications in health and disease. American Society of Clincal Nutrition, 76, pp.266S-73S. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/76/1/266S.full.pdf+html

Johnson, R.K., Appel, L., Brands, M., Howard, B., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R., Sacks, F., Steffen, L., & Wyllie-Rosett, J. (2009, September 15). Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation , 120(11), 1011-20. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627. Retrieved from http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/120/11/1011.full.pdf

Kearns, C., Apollonio, D. and Glantz, S. (2017). Sugar industry sponsorship of germ-free rodent studies linking sucrose to hyperlipidemia and cancer: An historical analysis of internal documents. PLOS Biology, 15(11), p.e2003460. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2003460

Kearns, C., Schmidt, L. and Glantz, S. (2016). Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(11), p.1680. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394

Lenoir, M., Serre, F., Cantin, L., & Ahmed, S. (2007). Intense Sweetness Surpasses Cocaine Reward. Plos ONE, 2(8), e698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000698

Lorincz, C., Manske, S. L., & Zernicke, R. (2009). Bone health. , 1(3), . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445243/

McGuire, M., Beerman, K. A., & William, M. (2011). Nutritional sciences: From fundamentals to food (with table of food composition booklet) (3rd ed.). Boston, MA, United States: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Mercola, J. (2005). Dr. Mercola's total health program. Schaumburg, IL: Mercola.com.

Schernhammer, E., Hu, F., Giovannucci, E., Michaud, D., Colditz, G., Stampfer, M. and Fuchs, C. (2005). Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drink Consumption and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in Two Prospective Cohorts. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 14(9), pp.2098-2105. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0059

Slattery, M., Benson, J., Berry, D., Duncan, D., Edwards, S., Caan, B. and Potter, J. (1997). Dietary sugar and colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 6, pp.677-685. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/cebp/6/9/677.full.pdf

Tjäderhane, L., & Larmas, M. (1998). A high sucrose diet decreases the mechanical strength of bones in growing rats. The Journal of nutrition., 128(10), 1807–10. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9772153

Tucker, K. L. (2014). Vegetarian diets and bone status. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(Supplement_1), 329S–335S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071621

U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th Edition ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; . Accessed March 8, 2016.