About Creatine Monohydrate

Creatine, appropriately named after the greek word (kreas) for meat, was first isolated from the meat of mammals in 1832 by Michael Eugene Chevreul (The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009). In 1847 creatine was later confirmed by Justus von LieBig to be a naturally occurring compound that could be found in the flesh of mammals, which was about ten times more prevalent in wild animals compared to captive animals. Liebig determined that increased physical activity was linked to increased creatine content (Bahrke, M. S., & Yesalis, C. E., 2002).

While there are many different types of synthetically produced creatine, the most commonly used and studied is creatine monohydrate. Besides naturally occurring creatine found in meat and fish, creatine comes in various forms, most commonly in powder, but is also available in pill or liquid form.

Creatine monohydrate is relatively inexpensive to purchase, but ranges from $4.78 (120 grams of powder) to $89.99 (120 count of capsules). Creatine monohydrate can be purchased online (via websites such as bodybuilding.com, gnc.com, etc.), in store (such as The Vitamin Shoppe, Walmart, etc.), even at many gyms (24 Hour Fitness, LA Fitness, etc.). Creatine supplementation is not prohibited or banned by the National Collegiate Athletic Association or the International Olympic Committee. Creatine use by athletes is considered a legal supplement and has been seen as safe at recommended doses.

While there are many different types of synthetically produced creatine, the most commonly used and studied is creatine monohydrate. Besides naturally occurring creatine found in meat and fish, creatine comes in various forms, most commonly in powder, but is also available in pill or liquid form.

Creatine monohydrate is relatively inexpensive to purchase, but ranges from $4.78 (120 grams of powder) to $89.99 (120 count of capsules). Creatine monohydrate can be purchased online (via websites such as bodybuilding.com, gnc.com, etc.), in store (such as The Vitamin Shoppe, Walmart, etc.), even at many gyms (24 Hour Fitness, LA Fitness, etc.). Creatine supplementation is not prohibited or banned by the National Collegiate Athletic Association or the International Olympic Committee. Creatine use by athletes is considered a legal supplement and has been seen as safe at recommended doses.

Physiology of Creatine

|

Creatine (N-Carbamimidoyl-N-methylglycine), also known as methylguanidinoacetic acid, is a naturally occurring compound within the human body. Creatine can be replenished by obtaining creatine in the diet or through endogenous synthesis from L-glycine, L-arginine, and L-methionine. The synthesis of creatine occurs primarily in the liver, kidneys and to some extent the pancreas. About 95% of the creatine within the body is stored in skeletal muscle, where it will be used to fuel short bouts of high intensity exercise. The effect of creatine supplementation on anaerobic exercise has demonstrated neuromuscular performance enhancing properties on short duration, predominately anaerobic, intermittent exercises (Buford et al., 2007). |

|

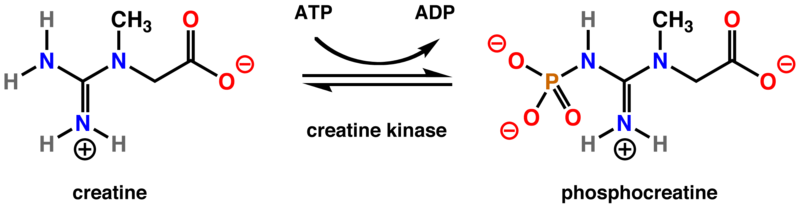

Creatine is used within the body in the form of phosphocreatine (PC) during short bouts of exercise (5-10 seconds) in order to fuel the need for quick, high-intensity, powerful movements. The energy is supplied when there is a donation of the phosphate group and its high energy bond from PC to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to form adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme creatine kinase (as seen in the figure below). ATP is broken down to ADP and inorganic phosphate, at the onset of exercise, then ATP is resynthesized via the PC reaction in the opposite direction. This system, ATP-PC or phosphagen system, provides a simple one-enzyme reaction to produce ATP for activities such as olympic weight-lifting, high jumping, or a football player sprinting down field. The largest disadvantage to this energy system is the limited supply of creatine phosphate. Increasing the pool of creatine phosphate within the muscle is similar in concept to increasing the size of a gas tank in a race car; increasing the size of a gas tank in a race car won't make it go faster but it will allow it to maintain its top speed for a longer duration. This is the same for our muscles, when you increase the creatine content inside the muscle you can prolong your high intensity workouts longer (Dunford & Doyle, 2011).

Though having a low solubility in water, creatine is thought to have a high bioavailability. Creatine supplementation appears to increase body mass but this is probably due more to intracellular water retention (which may stimulate muscle glycogen storage) rather than an increase in protein synthesis (Powers & Howley, 2014). Slight body weight changes are mostly from increased intramuscular water volume; water retention being a common side effect seen in the early stages of supplementation. More research needs to be conducted on water retention and increased work load on the kidneys (Kozlowski et al., n.d.).

Though having a low solubility in water, creatine is thought to have a high bioavailability. Creatine supplementation appears to increase body mass but this is probably due more to intracellular water retention (which may stimulate muscle glycogen storage) rather than an increase in protein synthesis (Powers & Howley, 2014). Slight body weight changes are mostly from increased intramuscular water volume; water retention being a common side effect seen in the early stages of supplementation. More research needs to be conducted on water retention and increased work load on the kidneys (Kozlowski et al., n.d.).

Research

Creatine monohydrate is the most widely research and the most effective supplement available to build muscle in a safe manner. In theory, supplementation of creatine monohydrate aids in the resynthesis of ATP, within the phosphagen system, making more creatine available in the muscle. Creatine monohydrate works most effectively for resistance-trained athletes for high intensity exercise and strength training.

Supplementation with creatine has been shown to improve body composition, anaerobic performance, muscular strength, muscular power, and muscular endurance (Camic et al., 2013), (Zuniga et al., 2011), (Candow, Chilibeck, Burke, Mueller, & Lewis, 2011).

In a double-blind study conducted by Cribb, et al., (2007) creatine monohydrate has demonstrated to promote create strength gains during resistance training, compared to carbohydrates alone.

Another study suggests that creatine supplementation can increase muscular strength, isokinetic peak torque and muscle cross sectional area (Souza-Junior, et al, 2007). The study also noted that resistance-trained athletes may benefit the most from supplementation with creatine monohydrate.

Research suggests that ingestion of carbohydrates with creatine supplementation enhances intramuscular creatine uptake and glycogen deposition and that creatine transport may be sodium dependent. In addition, ingestion of glucose and electrolytes with creatine promotes greater gains in fat-free mass, isotonic lifting volume, and sprint performance during intense resistance training (Kreider et al., 1998).

Supplementation with creatine has been shown to improve body composition, anaerobic performance, muscular strength, muscular power, and muscular endurance (Camic et al., 2013), (Zuniga et al., 2011), (Candow, Chilibeck, Burke, Mueller, & Lewis, 2011).

In a double-blind study conducted by Cribb, et al., (2007) creatine monohydrate has demonstrated to promote create strength gains during resistance training, compared to carbohydrates alone.

Another study suggests that creatine supplementation can increase muscular strength, isokinetic peak torque and muscle cross sectional area (Souza-Junior, et al, 2007). The study also noted that resistance-trained athletes may benefit the most from supplementation with creatine monohydrate.

Research suggests that ingestion of carbohydrates with creatine supplementation enhances intramuscular creatine uptake and glycogen deposition and that creatine transport may be sodium dependent. In addition, ingestion of glucose and electrolytes with creatine promotes greater gains in fat-free mass, isotonic lifting volume, and sprint performance during intense resistance training (Kreider et al., 1998).

Practical Considerations of Creatine Supplementation

The total creatine concentration within skeletal muscle is about 120 mmol ∙kg-1, and about 2 grams are excreted each day. These two grams are replaced by diet (1 gram) and by synthesis (1 gram) from amino acids (Powers & Howley, 2014).

Supplementing creatine can increase muscle creatine levels by approximately 20 percent. Creatine supplementation consists of a loading phase (20-25 g/day, for 5-6 days) and/or supplementing smaller amounts of creatine over a longer period of time (3-10 g/day, 1 month). In theory, supplementation and loading of creatine allows the muscle to maintain its ability to resynthesize ATP at a more consistent rate, allowing an athlete to train harder, potentially increasing strength, speed and power (Dunford & Doyle, 2011). However, the loading phase has been shown to have inconsistent results (Zuniga et al., 2011).

Supplementing with creatine doesn't necessarily mean its going to work for you if you already have a high amount of creatine in your skeletal muscles. Some people respond quite differently than others, so supplementation may or may not be for you. Subjects with high levels of creatine may not respond to an increase in muscle creatine levels (Powers & Howley, 2014). The maximum benefits of creatine can be seen in novice bodybuilders or athletes who do not have high amounts of creatine in their muscles.

Supplementing creatine can increase muscle creatine levels by approximately 20 percent. Creatine supplementation consists of a loading phase (20-25 g/day, for 5-6 days) and/or supplementing smaller amounts of creatine over a longer period of time (3-10 g/day, 1 month). In theory, supplementation and loading of creatine allows the muscle to maintain its ability to resynthesize ATP at a more consistent rate, allowing an athlete to train harder, potentially increasing strength, speed and power (Dunford & Doyle, 2011). However, the loading phase has been shown to have inconsistent results (Zuniga et al., 2011).

Supplementing with creatine doesn't necessarily mean its going to work for you if you already have a high amount of creatine in your skeletal muscles. Some people respond quite differently than others, so supplementation may or may not be for you. Subjects with high levels of creatine may not respond to an increase in muscle creatine levels (Powers & Howley, 2014). The maximum benefits of creatine can be seen in novice bodybuilders or athletes who do not have high amounts of creatine in their muscles.

References

Bahrke, M. S., & Yesalis, C. E. (2002). Performance-enhancing substances in sport and exercise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Buford, Thomas W, Richard B Kreider, Jeffrey R Stout, Mike Greenwood, Bill Campbell, Marie Spano, Tim Ziegenfuss, Hector Lopez, Jamie Landis, and Jose Antonio. "International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Creatine Supplementation and Exercise." J Int Soc Sports Nutr Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (2007): 6. Print.

Camic, C., Housh, T., Zuniga, J., Traylor, D., Bergstrom, H., Schmidt, R., … Housh, D. (2013). The effects of polyethylene glycosylated creatine supplementation on anaerobic performance measures and body composition. Journal of strength and conditioning research., 28(3), 825–33. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23897021

Candow, D., Chilibeck, P., Burke, D., Mueller, K., & Lewis, J. (2011). Effect of different frequencies of creatine supplementation on muscle size and strength in young adults. Journal of strength and conditioning research., 25(7), 1831–8. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21512399

Cribb, P. J., Williams, A. D., Stathis, C. G., Carey, M. F., & Hayes, A. (2007). Effects of Whey Isolate, Creatine, and Resistance Training on Muscle Hypertrophy. Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, 39(2), 298-307.

Dunford, M., & Doyle, A. J. (2011). Nutrition for sport and exercise - 2nd edition (2nd ed.). Boston, MA, United States: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Kozlowski, M., Williams, J., Sheffield, S., Volk, K., Ritchie, L., & Andrews, L. The influence of creatine on physiologic processes and exercise - Physiopedia, universal access to physiotherapy knowledge. Retrieved November 27, 2016, from Physio-pedia, http://www.physio-pedia.com/The_influence_of_creatine_on_physiologic_processes_and_exercise#cite_note-Juhn-21

Kreider, R., Ferreira, M., Wilson, M., Grindstaff, P., Plisk, S., Reinardy, J., … Almada, A. (1998). Effects of creatine supplementation on body composition, strength, and sprint performance. Medicine and science in sports and exercise., 30(1), 73–82. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9475647

Powers, S. K., & Howley, E. T. (2014). Exercise physiology: Theory and application to fitness and performance. New York, NY, United States: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Souza-Junior, T. P., et al. (2011) Strength and hypertrophy responses to constant and decreasing rest intervals in trained men using creatine supplementation. (2011). Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 8(1), 17-27.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2009). Michel-Eugene Chevreul | french chemist. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Michel-Eugene-Chevreul

Zuniga, J., Housh, T., Camic, C., Hendrix, C., Mielke, M., Johnson, G., … Schmidt, R. (2011). The effects of creatine monohydrate loading on anaerobic performance and one-repetition maximum strength. Journal of strength and conditioning research., 26(6), 1651–6. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21921817

Buford, Thomas W, Richard B Kreider, Jeffrey R Stout, Mike Greenwood, Bill Campbell, Marie Spano, Tim Ziegenfuss, Hector Lopez, Jamie Landis, and Jose Antonio. "International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Creatine Supplementation and Exercise." J Int Soc Sports Nutr Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (2007): 6. Print.

Camic, C., Housh, T., Zuniga, J., Traylor, D., Bergstrom, H., Schmidt, R., … Housh, D. (2013). The effects of polyethylene glycosylated creatine supplementation on anaerobic performance measures and body composition. Journal of strength and conditioning research., 28(3), 825–33. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23897021

Candow, D., Chilibeck, P., Burke, D., Mueller, K., & Lewis, J. (2011). Effect of different frequencies of creatine supplementation on muscle size and strength in young adults. Journal of strength and conditioning research., 25(7), 1831–8. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21512399

Cribb, P. J., Williams, A. D., Stathis, C. G., Carey, M. F., & Hayes, A. (2007). Effects of Whey Isolate, Creatine, and Resistance Training on Muscle Hypertrophy. Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, 39(2), 298-307.

Dunford, M., & Doyle, A. J. (2011). Nutrition for sport and exercise - 2nd edition (2nd ed.). Boston, MA, United States: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Kozlowski, M., Williams, J., Sheffield, S., Volk, K., Ritchie, L., & Andrews, L. The influence of creatine on physiologic processes and exercise - Physiopedia, universal access to physiotherapy knowledge. Retrieved November 27, 2016, from Physio-pedia, http://www.physio-pedia.com/The_influence_of_creatine_on_physiologic_processes_and_exercise#cite_note-Juhn-21

Kreider, R., Ferreira, M., Wilson, M., Grindstaff, P., Plisk, S., Reinardy, J., … Almada, A. (1998). Effects of creatine supplementation on body composition, strength, and sprint performance. Medicine and science in sports and exercise., 30(1), 73–82. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9475647

Powers, S. K., & Howley, E. T. (2014). Exercise physiology: Theory and application to fitness and performance. New York, NY, United States: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Souza-Junior, T. P., et al. (2011) Strength and hypertrophy responses to constant and decreasing rest intervals in trained men using creatine supplementation. (2011). Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 8(1), 17-27.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2009). Michel-Eugene Chevreul | french chemist. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Michel-Eugene-Chevreul

Zuniga, J., Housh, T., Camic, C., Hendrix, C., Mielke, M., Johnson, G., … Schmidt, R. (2011). The effects of creatine monohydrate loading on anaerobic performance and one-repetition maximum strength. Journal of strength and conditioning research., 26(6), 1651–6. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21921817