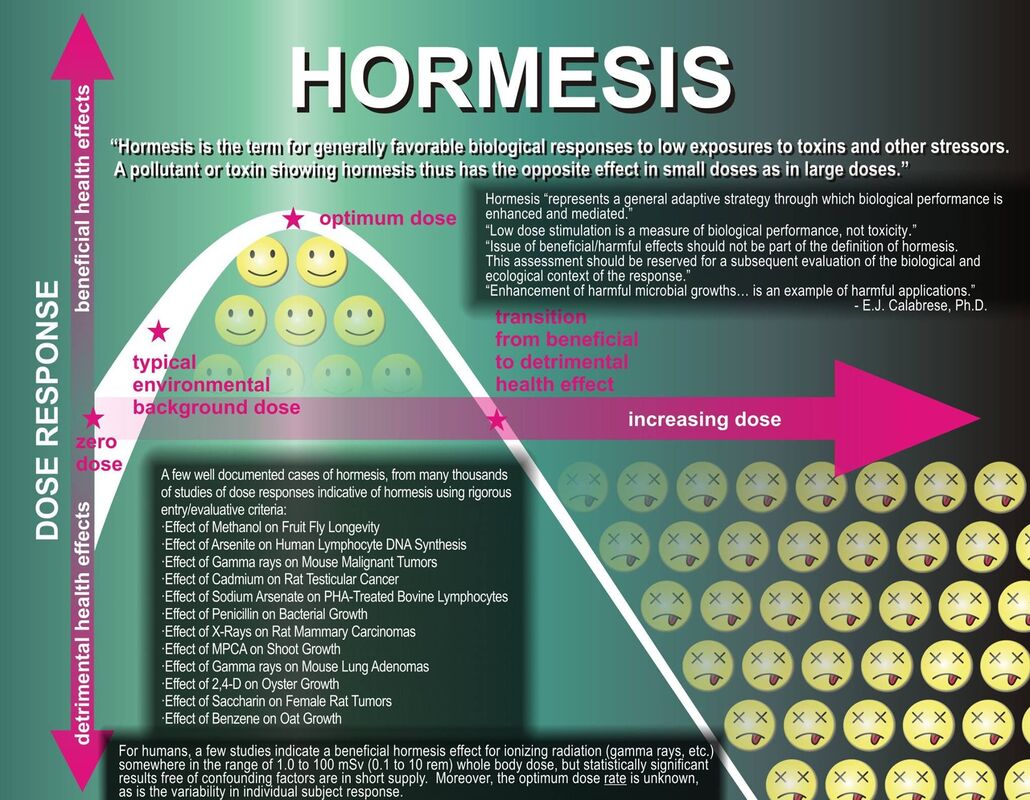

Perhaps you have heard the phrase, "what doesn't kill you makes you stronger." Well, it's true, to a degree - there is a point at which some stressor will make you weaker. This phrase is based on hormesis. Hormesis is a biological phenomenon characterized by a biphasic response to a substance or stressor, where low doses of the stressor have a beneficial effect, while higher doses or prolonged exposure may be harmful. In other words, it suggests that exposure to moderate stress or toxins can trigger adaptive responses in organisms, leading to improved resilience and enhanced functionality.

Understanding hormesis has implications for various fields, including toxicology, medicine, and public health. It emphasizes the importance of considering both the dose and duration of exposure when evaluating the effects of stressors on biological systems. Researchers continue to explore the applications of hormesis in optimizing health, preventing diseases, and developing more accurate risk assessments for environmental exposures.

Understanding hormesis has implications for various fields, including toxicology, medicine, and public health. It emphasizes the importance of considering both the dose and duration of exposure when evaluating the effects of stressors on biological systems. Researchers continue to explore the applications of hormesis in optimizing health, preventing diseases, and developing more accurate risk assessments for environmental exposures.

biphasic response

Hormesis involves a dose-response relationship with two phases. At low doses, the stressor has a positive or stimulatory effect on biological systems, while at higher doses, it can have detrimental or inhibitory effects.

The concept of a "biphasic response" is fundamental to understanding hormesis. It describes the characteristic dose-response relationship observed in hormetic processes, where a substance or stressor elicits opposite effects at low and high doses. The response can be visualized as a U-shaped or J-shaped curve, illustrating the beneficial effects at low doses and potential harm at higher doses.

The concept of a "biphasic response" is fundamental to understanding hormesis. It describes the characteristic dose-response relationship observed in hormetic processes, where a substance or stressor elicits opposite effects at low and high doses. The response can be visualized as a U-shaped or J-shaped curve, illustrating the beneficial effects at low doses and potential harm at higher doses.

Below are the following elements of the hormetic biphasic response:

The biphasic response is context-dependent, varying based on the type of stressor, the organism's characteristics, and the specific biological processes involved. Different stressors may induce hormesis in different ways, and the optimal hormetic zone can vary widely.

Understanding the biphasic response is important in applications related to health and medicine. For instance, in pharmacology, it challenges the traditional linear dose-response models and encourages a more nuanced consideration of optimal dosing for therapeutic effects. The biphasic response in hormesis reflects the dual nature of the biological response to stressors, with a beneficial phase at low doses and a detrimental phase at higher doses. This concept has implications for risk assessment, pharmacology, and strategies aimed at optimizing health through controlled exposure to stressors.

- Low Dose (Beneficial Phase):

- At low doses of a stressor, organisms often exhibit a positive or stimulatory response. This phase is characterized by adaptive, protective, or hormetic effects.

- Examples of beneficial responses include improved resilience, enhanced cellular repair mechanisms, increased antioxidant production, and activation of stress response pathways.

- The low-dose exposure triggers adaptive mechanisms that prepare the organism to better handle subsequent stressors.

- Moderate Dose (Hormetic Zone):

- The hormetic zone represents the range of doses where the beneficial effects peak. Within this range, the stressor induces an optimal adaptive response, promoting health and resilience.

- The hormetic zone is the sweet spot where the organism experiences the most significant positive effects, such as improved physiological functions, increased resistance to oxidative stress, and enhanced longevity.

- High Dose (Detrimental Phase):

- Beyond the hormetic zone, as the dose of the stressor increases, the response may shift from adaptive and beneficial to harmful or inhibitory.

- The detrimental phase is characterized by toxic effects, cellular damage, and a decline in the organism's overall well-being.

- The switch from beneficial to detrimental effects is a crucial aspect of the biphasic response, emphasizing the dose-dependent nature of hormesis.

- Threshold Effect:

- The concept of a threshold is crucial in understanding the biphasic response. Below a certain threshold, the stressor may not elicit a response, and the organism remains unaffected. As the dose increases beyond this threshold, the hormetic response becomes apparent

The biphasic response is context-dependent, varying based on the type of stressor, the organism's characteristics, and the specific biological processes involved. Different stressors may induce hormesis in different ways, and the optimal hormetic zone can vary widely.

Understanding the biphasic response is important in applications related to health and medicine. For instance, in pharmacology, it challenges the traditional linear dose-response models and encourages a more nuanced consideration of optimal dosing for therapeutic effects. The biphasic response in hormesis reflects the dual nature of the biological response to stressors, with a beneficial phase at low doses and a detrimental phase at higher doses. This concept has implications for risk assessment, pharmacology, and strategies aimed at optimizing health through controlled exposure to stressors.

adaptive response

The concept of hormesis suggests that exposure to mild stressors can activate adaptive and protective mechanisms within cells and organisms. These adaptations are often protective and can improve the ability to respond to more severe stressors. Instead of causing harm, mild stressors in hormetic doses stimulate the organism's resilience and ability to cope with more severe stressors. The adaptive response in hormesis involves various molecular, cellular, and systemic changes that contribute to enhanced health and resilience.

At the cellular level, hormetic stressors activate stress response pathways, such as the heat shock response and the unfolded protein response. These pathways lead to the production of heat shock proteins and other molecular chaperones that help cells cope with and repair damage.

Low levels of oxidative stress induced by hormetic stressors trigger the activation of antioxidant defense mechanisms. Cells upregulate the production of endogenous antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione, to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and prevent oxidative damage.

Exposure to hormetic stressors can stimulate DNA repair mechanisms. Cells activate pathways involved in repairing damaged DNA, reducing the likelihood of mutations and genomic instability. This contributes to the maintenance of genomic integrity.

Hormesis has been linked to increased mitochondrial biogenesis, the process by which cells produce new mitochondria. Mitochondria are crucial for energy production, and enhancing their number and function through hormesis supports cellular energy balance and resilience.

Autophagy, the cellular process of recycling damaged or dysfunctional cellular components, is often upregulated in response to hormetic stress. This process helps maintain cellular homeostasis by removing debris and promoting the turnover of cellular components.

Hormetic stressors can modulate the immune system, promoting a balanced and adaptive immune response. This may involve enhancing immune cell function, improving immune surveillance, and promoting a controlled inflammatory response.

In the nervous system, hormesis has been associated with neuroprotective effects. Low levels of stressors may stimulate the release of neurotrophic factors, support synaptic plasticity, and enhance the resilience of neurons against subsequent challenges.

Hormetic responses have been implicated in the extension of lifespan and the promotion of healthy aging. By activating adaptive mechanisms, hormesis may contribute to slowing down the aging process and reducing the risk of age-related diseases.

Beyond the cellular level, hormetic stressors can induce systemic adaptations. These may include improvements in metabolic function, hormonal balance, and overall physiological resilience. The adaptive response in hormesis highlights the dynamic and plastic nature of biological systems. Rather than causing harm, mild stressors prompt the organism to activate a suite of adaptive and protective mechanisms, promoting overall health and resilience. The specific mechanisms involved can vary depending on the nature of the stressor and the biological context.

At the cellular level, hormetic stressors activate stress response pathways, such as the heat shock response and the unfolded protein response. These pathways lead to the production of heat shock proteins and other molecular chaperones that help cells cope with and repair damage.

Low levels of oxidative stress induced by hormetic stressors trigger the activation of antioxidant defense mechanisms. Cells upregulate the production of endogenous antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione, to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and prevent oxidative damage.

Exposure to hormetic stressors can stimulate DNA repair mechanisms. Cells activate pathways involved in repairing damaged DNA, reducing the likelihood of mutations and genomic instability. This contributes to the maintenance of genomic integrity.

Hormesis has been linked to increased mitochondrial biogenesis, the process by which cells produce new mitochondria. Mitochondria are crucial for energy production, and enhancing their number and function through hormesis supports cellular energy balance and resilience.

Autophagy, the cellular process of recycling damaged or dysfunctional cellular components, is often upregulated in response to hormetic stress. This process helps maintain cellular homeostasis by removing debris and promoting the turnover of cellular components.

Hormetic stressors can modulate the immune system, promoting a balanced and adaptive immune response. This may involve enhancing immune cell function, improving immune surveillance, and promoting a controlled inflammatory response.

In the nervous system, hormesis has been associated with neuroprotective effects. Low levels of stressors may stimulate the release of neurotrophic factors, support synaptic plasticity, and enhance the resilience of neurons against subsequent challenges.

Hormetic responses have been implicated in the extension of lifespan and the promotion of healthy aging. By activating adaptive mechanisms, hormesis may contribute to slowing down the aging process and reducing the risk of age-related diseases.

Beyond the cellular level, hormetic stressors can induce systemic adaptations. These may include improvements in metabolic function, hormonal balance, and overall physiological resilience. The adaptive response in hormesis highlights the dynamic and plastic nature of biological systems. Rather than causing harm, mild stressors prompt the organism to activate a suite of adaptive and protective mechanisms, promoting overall health and resilience. The specific mechanisms involved can vary depending on the nature of the stressor and the biological context.

examples of hormesis

Hormetic responses can be observed in various contexts, including exercise, exposure to certain chemicals, dietary factors, and even radiation from cell phones. For instance, moderate physical exercise is a stressor that induces beneficial adaptations in the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems.

Exercise

Exercise acts as a hormetic stressor by exposing the body to controlled and moderate levels of physical stress, which triggers adaptive responses that enhance overall health and resilience. Hormesis is a biological phenomenon where exposure to low levels of stress or toxins induces adaptive responses that result in beneficial effects. Here's how exercise functions as a hormetic stressor:

- Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense:

- Stress Induction: Exercise, especially intense or prolonged forms, generates oxidative stress within the body. This oxidative stress results from an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) during activities like aerobic and resistance training.

- Adaptive Response: In response to oxidative stress, the body activates its antioxidant defense mechanisms. This includes the increased production of endogenous antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione, to neutralize ROS and prevent cellular damage.

- Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs):

- Stress Induction: Exercise, particularly high-intensity and endurance training, induces heat stress within the body.

- Adaptive Response: The heat stress activates the production of heat shock proteins (HSPs), which act as molecular chaperones. HSPs help maintain protein structure, assist in cellular repair, and enhance cellular resilience to various stressors.

- Inflammation and Immune Response:

- Stress Induction: Exercise can cause microtrauma to muscle fibers, leading to localized inflammation.

- Adaptive Response: The inflammatory response triggers the activation of immune cells, promoting tissue repair and regeneration. This process contributes to the strengthening of the immune system and adaptation to future stressors.

- Mitochondrial Biogenesis:

- Stress Induction: Exercise, particularly aerobic activities, increases energy demand and can lead to mitochondrial stress.

- Adaptive Response: In response to mitochondrial stress, the body undergoes mitochondrial biogenesis—producing more mitochondria. This enhances the efficiency of energy production and contributes to improved metabolic function.

- Neuroplasticity and Brain Health:

- Stress Induction: Exercise challenges the nervous system and induces stress on brain cells.

- Adaptive Response: The brain responds by releasing neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which support neuroplasticity, neuronal growth, and cognitive function. Regular exercise is associated with improved mood, cognitive function, and overall brain health.

- Endocrine Adaptations:

- Stress Induction: Exercise influences hormonal levels, including the release of stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline.

- Adaptive Response: Hormonal adaptations contribute to improvements in metabolism, energy utilization, and the body's ability to handle stress. Exercise can also enhance insulin sensitivity and regulate other endocrine functions.

- Adaptive Immune Function:

- Stress Induction: Exercise has been shown to temporarily suppress certain aspects of the immune system immediately after intense sessions.

- Adaptive Response: Regular, moderate exercise, on the other hand, enhances overall immune function over time. It contributes to a balanced immune response, reducing the risk of chronic inflammation and related conditions.

- Ischemic Preconditioning:

- Stress Induction: Brief episodes of reduced blood flow to tissues.

- Adaptive Response: Improved blood flow, enhanced tissue resilience, and protection against subsequent ischemic events.

- Stress Induction: Brief episodes of reduced blood flow to tissues.

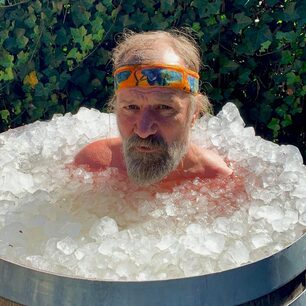

Temperature

Sauna exposure and cold water immersion are also examples of environmental stressors that can act as hormetic stressors, triggering adaptive responses in the body. These practices involve exposing the body to extreme temperatures and elicit physiological changes that contribute to improved resilience and health.

Sauna exposure involves sitting in a heated room, typically at temperatures ranging from 160 to 200 degrees Fahrenheit (71 to 93 degrees Celsius). This creates a state of hyperthermia, or elevated body temperature, which is a form of thermal stress. The heat stress from the sauna induces the production of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in cells. HSPs act as molecular chaperones, helping to repair and maintain the structure of cellular proteins. This is a key adaptive response to the stress of elevated temperatures. Exposure to heat leads to vasodilation, an expansion of blood vessels, which increases blood flow to various tissues. This promotes nutrient delivery, oxygenation, and removal of waste products, contributing to tissue repair and recovery.

Cold water immersion involves exposing the body to cold water, typically with temperatures ranging from 50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 15 degrees Celsius). This induces a state of hypothermia, or reduced body temperature, which is a form of cold stress. Cold exposure activates brown adipose tissue (BAT), a type of fat tissue that generates heat through thermogenesis. This process helps the body maintain a stable internal temperature and increases energy expenditure. Cold stress induces the expression of cold shock proteins, which are involved in protecting cells from the damaging effects of cold temperatures. These proteins play a role in cellular adaptation to cold stress. Cold exposure initially causes vasoconstriction, narrowing of blood vessels, to conserve heat. Upon rewarming, there is vasodilation, improving circulation and promoting nutrient delivery to tissues.

Both sauna and cold water immersion share some common mechanisms, such as the activation of the autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is activated during cold exposure, while the parasympathetic nervous system may dominate during sauna exposure. These shifts in the autonomic nervous system contribute to the overall adaptive response to temperature stress. The repeated exposure to sauna and cold water immersion, when done in a controlled and gradual manner, promotes overall adaptation and resilience. The body becomes more efficient at responding to changes in temperature, and the adaptive responses contribute to improved cardiovascular function, immune system modulation, and stress resilience.

It's important to note that individual responses to sauna and cold water immersion can vary, and these practices should be approached gradually and with consideration for individual health conditions. Consulting with a healthcare professional before incorporating these practices, especially for individuals with pre-existing health conditions, is advisable.

Sauna exposure involves sitting in a heated room, typically at temperatures ranging from 160 to 200 degrees Fahrenheit (71 to 93 degrees Celsius). This creates a state of hyperthermia, or elevated body temperature, which is a form of thermal stress. The heat stress from the sauna induces the production of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in cells. HSPs act as molecular chaperones, helping to repair and maintain the structure of cellular proteins. This is a key adaptive response to the stress of elevated temperatures. Exposure to heat leads to vasodilation, an expansion of blood vessels, which increases blood flow to various tissues. This promotes nutrient delivery, oxygenation, and removal of waste products, contributing to tissue repair and recovery.

Cold water immersion involves exposing the body to cold water, typically with temperatures ranging from 50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 15 degrees Celsius). This induces a state of hypothermia, or reduced body temperature, which is a form of cold stress. Cold exposure activates brown adipose tissue (BAT), a type of fat tissue that generates heat through thermogenesis. This process helps the body maintain a stable internal temperature and increases energy expenditure. Cold stress induces the expression of cold shock proteins, which are involved in protecting cells from the damaging effects of cold temperatures. These proteins play a role in cellular adaptation to cold stress. Cold exposure initially causes vasoconstriction, narrowing of blood vessels, to conserve heat. Upon rewarming, there is vasodilation, improving circulation and promoting nutrient delivery to tissues.

Both sauna and cold water immersion share some common mechanisms, such as the activation of the autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is activated during cold exposure, while the parasympathetic nervous system may dominate during sauna exposure. These shifts in the autonomic nervous system contribute to the overall adaptive response to temperature stress. The repeated exposure to sauna and cold water immersion, when done in a controlled and gradual manner, promotes overall adaptation and resilience. The body becomes more efficient at responding to changes in temperature, and the adaptive responses contribute to improved cardiovascular function, immune system modulation, and stress resilience.

It's important to note that individual responses to sauna and cold water immersion can vary, and these practices should be approached gradually and with consideration for individual health conditions. Consulting with a healthcare professional before incorporating these practices, especially for individuals with pre-existing health conditions, is advisable.

Calories and nutrition factors

Hormesis can be induced by a variety of stressors, and many substances or practices exhibit hormetic effects. Here are some additional nutritional examples of hormetic stressors:

It's important to recognize that the effectiveness of hormetic stressors can vary based on individual factors, and the optimal dose or duration may differ for each stressor. Additionally, the line between a beneficial hormetic response and harmful stress can be fine, emphasizing the importance of moderation and individualization. Always consult with healthcare professionals before attempting any stress-inducing practices, especially for individuals with pre-existing health conditions.

- Caloric Restriction:

- Stress Induction: Reduced calorie intake below normal levels.

- Adaptive Response: Activation of cellular repair mechanisms, improved metabolic efficiency, and increased resistance to age-related diseases. Caloric restriction has been linked to increased lifespan and healthspan in various organisms.

- Intermittent Fasting:

- Stress Induction: Alternating cycles of eating and fasting.

- Adaptive Response: Improved insulin sensitivity, metabolic flexibility, and cellular autophagy. Intermittent fasting has been associated with benefits for weight management and metabolic health.

- Phytochemicals and Antioxidants:

- Stress Induction: Consumption of plant-derived compounds with mild antioxidant properties (e.g., polyphenols).

- Adaptive Response: Induction of endogenous antioxidant defenses, reduction in oxidative stress, and potential anti-inflammatory effects. Foods rich in antioxidants include berries, green tea, and dark chocolate.

It's important to recognize that the effectiveness of hormetic stressors can vary based on individual factors, and the optimal dose or duration may differ for each stressor. Additionally, the line between a beneficial hormetic response and harmful stress can be fine, emphasizing the importance of moderation and individualization. Always consult with healthcare professionals before attempting any stress-inducing practices, especially for individuals with pre-existing health conditions.

health implications

Hormesis has profound implications for health and longevity due to its role in promoting adaptive responses that enhance overall resilience and well-being. A variety of physiologic mechanisms underlie the benefits of hormesis with respect to health and longevity, including but not limited to:

While hormesis holds promise for promoting health and longevity, it's essential to emphasize the importance of moderation, individualization, and considering the specific context of each hormetic stressor. Additionally, the cumulative impact of various hormetic interventions and lifestyle factors is likely to be influential in achieving optimal health and extending lifespan. Always consult with healthcare professionals before adopting new interventions, especially for individuals with existing health conditions.

- Cellular Repair and Maintenance:

- Hormetic Stressors: Exposure to mild stressors, such as exercise, caloric restriction, and phytochemicals, induces cellular responses that activate repair mechanisms.

- Implications: Enhanced cellular repair and maintenance contribute to the preservation of genomic integrity, reduction in the accumulation of damage, and overall cellular resilience.

- Oxidative Stress Management:

- Hormetic Stressors: Exposure to moderate levels of oxidative stress, as seen in exercise or certain phytochemicals, triggers the activation of antioxidant defense mechanisms.

- Implications: Improved management of oxidative stress helps prevent chronic oxidative damage, reduces the risk of age-related diseases, and supports longevity.

- Mitochondrial Biogenesis:

- Hormetic Stressors: Activities like exercise stimulate mitochondrial stress, leading to increased mitochondrial biogenesis.

- Implications: Efficient and numerous mitochondria contribute to improved energy production, metabolic function, and protection against age-related decline in mitochondrial function.

- Enhanced Immune Function:

- Hormetic Stressors: Exercise and certain dietary interventions can induce mild stress, promoting adaptive immune responses.

- Implications: Improved immune function helps the body defend against infections, reduces inflammation, and contributes to overall health and longevity.

- Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Health:

- Hormetic Stressors: Exercise and cognitive challenges induce stress on the brain, leading to the release of neurotrophic factors.

- Implications: Neurotrophic factors support neuroplasticity, enhance cognitive function, and may contribute to a reduced risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

- Hormonal Adaptations:

- Hormetic Stressors: Hormonal changes induced by stressors like exercise can have positive effects on metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and overall hormonal balance.

- Implications: Improved hormonal regulation contributes to metabolic health, reduced risk of diabetes, and may have anti-aging effects.

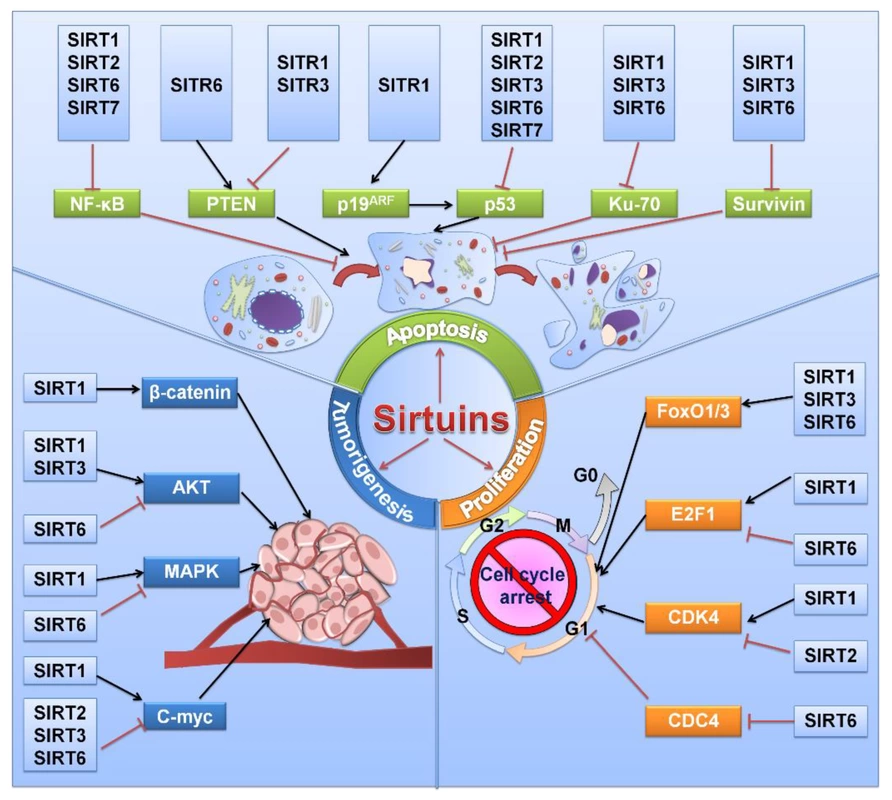

- Longevity Pathways Activation:

- Hormetic Stressors: Some hormetic stressors, such as caloric restriction and certain compounds like resveratrol, activate longevity-related pathways, including sirtuins.

- Implications: Activation of longevity pathways may contribute to the extension of lifespan and healthspan.

- Adaptive Responses to Environmental Stressors:

- Hormetic Stressors: Exposure to environmental stressors, such as heat or cold, induces adaptive responses.

- Implications: Improved tolerance to environmental stressors enhances the body's ability to cope with diverse challenges, contributing to overall resilience.

- Reduction of Chronic Inflammation:

- Hormetic Stressors: Some hormetic interventions, including exercise, may help modulate the inflammatory response.

- Implications: Reduction in chronic inflammation is associated with a lower risk of chronic diseases and may positively impact aging processes.

- Prevention of Age-Related Diseases:

- Hormetic Stressors: By promoting cellular and systemic adaptations, hormetic stressors may help prevent or delay the onset of age-related diseases.

- Implications: Reduction in the incidence of diseases such as cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic diseases contributes to increased longevity.

While hormesis holds promise for promoting health and longevity, it's essential to emphasize the importance of moderation, individualization, and considering the specific context of each hormetic stressor. Additionally, the cumulative impact of various hormetic interventions and lifestyle factors is likely to be influential in achieving optimal health and extending lifespan. Always consult with healthcare professionals before adopting new interventions, especially for individuals with existing health conditions.

influence on Longevity

Hormesis, through its influence on sirtuins and telomeres, contributes to cellular resilience and anti-aging mechanisms.

Sirtuins are a family of proteins that play a crucial role in regulating cellular processes involved in metabolism, DNA repair, and longevity. They are known to be activated in response to various stressors, such as caloric restriction, exercise, and certain polyphenols (e.g., resveratrol), among other movement, nutrition, and lifestyle factors.

Hormetic stressors, which involve mild and controlled stress, can activate sirtuins as part of the cellular response. Sirtuins act as deacetylases, influencing the acetylation of various proteins, including those involved in DNA repair and gene expression.

The activation of sirtuins through hormesis is linked to improved mitochondrial function, enhanced DNA repair mechanisms, and increased resistance to oxidative stress. These adaptations contribute to overall cellular health and have implications for longevity by promoting resilience and delaying age-related decline.

Sirtuins are a family of proteins that play a crucial role in regulating cellular processes involved in metabolism, DNA repair, and longevity. They are known to be activated in response to various stressors, such as caloric restriction, exercise, and certain polyphenols (e.g., resveratrol), among other movement, nutrition, and lifestyle factors.

Hormetic stressors, which involve mild and controlled stress, can activate sirtuins as part of the cellular response. Sirtuins act as deacetylases, influencing the acetylation of various proteins, including those involved in DNA repair and gene expression.

The activation of sirtuins through hormesis is linked to improved mitochondrial function, enhanced DNA repair mechanisms, and increased resistance to oxidative stress. These adaptations contribute to overall cellular health and have implications for longevity by promoting resilience and delaying age-related decline.

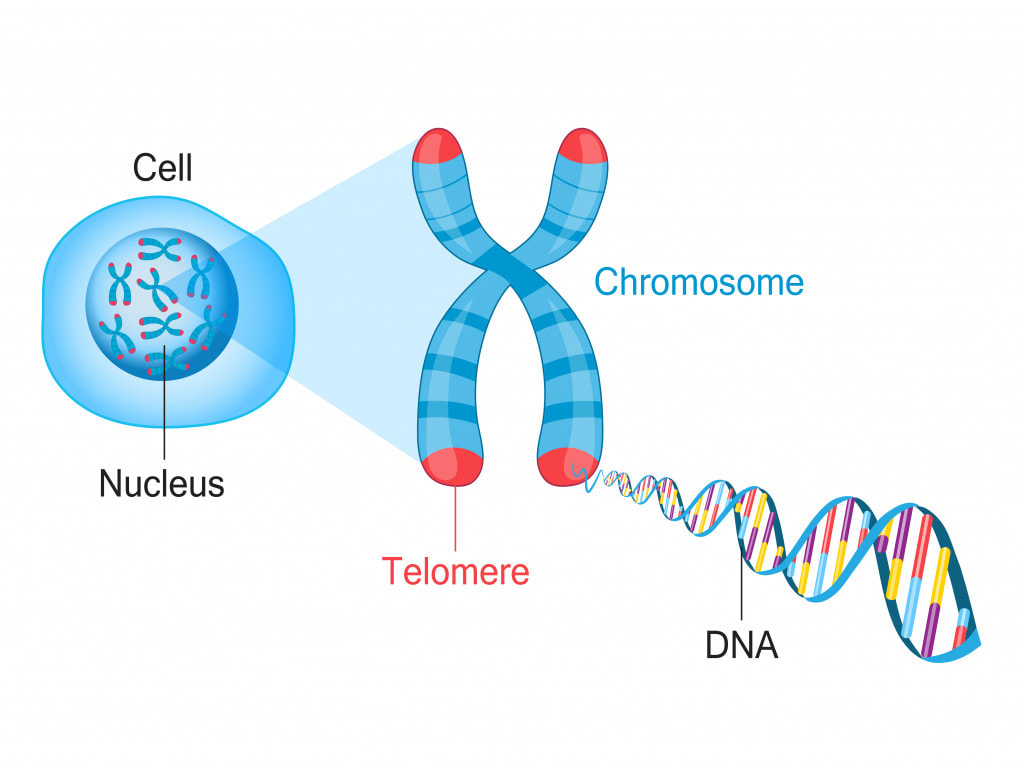

Telomeres are protective structures at the ends of chromosomes that shorten with each cell division. Telomere length is considered a marker of cellular aging, and shortened telomeres can contribute to cellular senescence.

Hormetic stressors may impact telomere length and maintenance. Chronic stress and inflammation are associated with accelerated telomere shortening, while certain hormetic interventions, such as exercise and certain dietary factors, may contribute to telomere maintenance or even elongation.

Preserving telomere length is linked to prolonged cellular lifespan and reduced susceptibility to age-related diseases. Hormetic interventions that positively influence telomeres may contribute to longevity by supporting cellular health and delaying the onset of cellular senescence.

Hormetic stressors may impact telomere length and maintenance. Chronic stress and inflammation are associated with accelerated telomere shortening, while certain hormetic interventions, such as exercise and certain dietary factors, may contribute to telomere maintenance or even elongation.

Preserving telomere length is linked to prolonged cellular lifespan and reduced susceptibility to age-related diseases. Hormetic interventions that positively influence telomeres may contribute to longevity by supporting cellular health and delaying the onset of cellular senescence.

Sirtuins and telomeres are interconnected in cellular processes. Sirtuins, especially SIRT6, have been implicated in the regulation of telomere maintenance and protection. Conversely, telomere dysfunction can impact the activity of sirtuins.

Hormetic stressors, through their impact on sirtuins and other cellular processes, may contribute to maintaining the delicate balance in the regulation of telomeres. For instance, by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, hormesis may indirectly support telomere integrity. The synergistic effects of hormetic interventions on sirtuins and telomeres have implications for cellular resilience, anti-aging mechanisms, and the potential to delay the onset of age-related diseases.

The hormetic activation of sirtuins and potential effects on telomeres contribute to enhanced cellular health and resilience. This, in turn, has implications for overall health and longevity by reducing the risk of chronic diseases associated with aging. The interconnected regulation of sirtuins and telomeres by hormetic stressors aligns with anti-aging mechanisms. Cellular adaptations, such as improved DNA repair, mitochondrial function, and telomere maintenance, collectively support healthy aging and potentially extend lifespan.

The activation of sirtuins and maintenance of telomeres are part of the broader cellular responses to mild stressors, and their coordinated regulation has implications for promoting health and longevity. However, it's important to note that the field of sirtuins, telomeres, and hormesis is complex, and ongoing research continues to explore the nuanced interactions and their impact on aging and longevity.

Hormetic stressors, through their impact on sirtuins and other cellular processes, may contribute to maintaining the delicate balance in the regulation of telomeres. For instance, by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, hormesis may indirectly support telomere integrity. The synergistic effects of hormetic interventions on sirtuins and telomeres have implications for cellular resilience, anti-aging mechanisms, and the potential to delay the onset of age-related diseases.

The hormetic activation of sirtuins and potential effects on telomeres contribute to enhanced cellular health and resilience. This, in turn, has implications for overall health and longevity by reducing the risk of chronic diseases associated with aging. The interconnected regulation of sirtuins and telomeres by hormetic stressors aligns with anti-aging mechanisms. Cellular adaptations, such as improved DNA repair, mitochondrial function, and telomere maintenance, collectively support healthy aging and potentially extend lifespan.

The activation of sirtuins and maintenance of telomeres are part of the broader cellular responses to mild stressors, and their coordinated regulation has implications for promoting health and longevity. However, it's important to note that the field of sirtuins, telomeres, and hormesis is complex, and ongoing research continues to explore the nuanced interactions and their impact on aging and longevity.

Toxicology and medicine

- Toxicology and Medicine: In toxicology, hormesis challenges the traditional linear no-threshold model, which assumes that any level of exposure to a toxic substance carries some level of risk. Hormetic responses are considered in developing more nuanced risk assessments.

Here are key aspects of hormesis in the context of toxicology:

- Biphasic Response:

- Low Doses vs. High Doses: Hormesis is characterized by a U-shaped or J-shaped dose-response curve. At low doses, the substance may elicit a positive response or even be protective, while at higher doses, the response becomes adverse or toxic.

- Beneficial Effects at Low Doses:

- Stimulation and Adaptation: In hormesis, exposure to low doses of a toxic substance can stimulate adaptive responses in the organism. These adaptive responses may include enhanced repair mechanisms, improved cellular defenses, or activation of protective pathways.

- Examples of Hormetic Responses:

- Radiation: Low doses of ionizing radiation have been reported to induce hormetic responses, potentially leading to improved DNA repair mechanisms and cellular resilience.

- Phytochemicals: Certain plant compounds, such as polyphenols in fruits and vegetables, exhibit hormetic effects. At low concentrations, they may have antioxidant properties and stimulate cellular defense mechanisms.

- Thresholds and Nonlinearity:

- Threshold Phenomenon: Hormesis challenges the traditional toxicological concept of a no-observable-adverse-effect level (NOAEL). In hormesis, there is a recognition that even at low doses, a response may be observed, but it could be beneficial rather than adverse.

- Nonlinear Response: The dose-response curve in hormesis is nonlinear, illustrating that the relationship between dose and response is not constant but varies across the dose range.

- Implications for Risk Assessment:

- Challenges in Traditional Risk Assessment: Hormesis introduces challenges to the conventional methods of risk assessment, which often assume a linear relationship between dose and response. This may result in overestimation of risks at low doses or lead to unnecessary regulatory measures.

- Practical Considerations:

- Dose-Dependent Effects: The concept of hormesis underscores the importance of considering dose-dependent effects when assessing the toxicity of substances. What may be toxic at high doses might have different effects or even be beneficial at low doses.

- Controversies and Debate:

- Scientific Debate: Hormesis has been a subject of scientific debate and controversy. While there is evidence supporting hormetic responses for certain substances, the applicability and generalizability of hormesis across different chemicals and biological systems are still areas of ongoing research and discussion.

dose-dependent effect

The effectiveness of hormesis is dose-dependent, and the optimal level of stress varies among individuals and contexts. Too little stress may not induce a response, while too much stress can lead to harmful effects.

In other words, hormesis is a dose-response phenomenon characterized by a biphasic relationship between the dose of a substance and the biological response it elicits. Unlike the traditional linear dose-response model, which assumes that the response increases or decreases proportionally with the dose, hormesis introduces the concept that low doses of a stressor can induce a beneficial or stimulatory response, while higher doses may lead to toxic or inhibitory effects.

Here's an elaboration on hormesis with respect to the dose-dependent effect:

In other words, hormesis is a dose-response phenomenon characterized by a biphasic relationship between the dose of a substance and the biological response it elicits. Unlike the traditional linear dose-response model, which assumes that the response increases or decreases proportionally with the dose, hormesis introduces the concept that low doses of a stressor can induce a beneficial or stimulatory response, while higher doses may lead to toxic or inhibitory effects.

Here's an elaboration on hormesis with respect to the dose-dependent effect:

- Biphasic Dose-Response Curve:

- Low Doses: At low doses, the response is not only non-toxic but may be beneficial. This phase is often characterized by stimulation, adaptation, or hormetic responses that enhance the organism's resilience or functioning.

- High Doses: As the dose increases, the response may eventually reach a point where it becomes adverse or toxic. This phase is associated with inhibitory or detrimental effects.

- Threshold and Nonlinear Relationship:

- Threshold Phenomenon: Hormesis challenges the traditional toxicological concept of a threshold, suggesting that even at doses below traditionally defined thresholds, a response can be observed.

- Nonlinear Response: The dose-response relationship in hormesis is nonlinear, meaning that the relationship between dose and response is not constant but varies across different dose ranges.

- Examples of Hormetic Responses:

- Radiation: Low doses of ionizing radiation may induce a hormetic response, potentially leading to improved DNA repair mechanisms and cellular resilience.

- Exercise: Physical exercise is an example of hormesis, where moderate levels of stress on the body lead to adaptive responses, improving cardiovascular health, metabolic efficiency, and overall fitness.

- Dose-Dependent Adaptive Responses:

- Stimulation of Adaptive Mechanisms: At low doses, the stressor activates adaptive mechanisms within the organism. This may include the upregulation of antioxidant defenses, DNA repair pathways, or other protective mechanisms.

- Enhanced Resilience: Hormetic responses at low doses contribute to enhanced resilience against subsequent exposures to stressors, providing a form of preconditioning or priming.

- Implications for Risk Assessment:

- Challenge to Linear Extrapolation: Hormesis challenges the practice of linear extrapolation commonly used in risk assessment. Extrapolating linearly from high-dose toxicology studies to predict effects at lower doses may not accurately reflect hormetic responses.

- Consideration of Low-Dose Effects: Understanding hormesis emphasizes the need to consider potential beneficial effects or adaptations that might occur at low doses, which may be overlooked in traditional risk assessments.

- Context Dependency:

- Dependence on Substance and Context: Hormesis is substance-specific and context-dependent. The dose range and the nature of the stressor, as well as the biological system under consideration, can all influence the occurrence and magnitude of hormetic responses.

- Regulatory and Therapeutic Implications:

- Regulatory Challenges: Hormesis poses challenges to regulatory frameworks that traditionally rely on linear extrapolation for setting exposure limits. It calls for a more nuanced and dose-dependent approach to risk assessment.

- Therapeutic Potential: Recognizing hormesis has implications for therapeutic interventions. Some substances or interventions that induce hormetic responses at low doses might be explored for potential health benefits.

Resilience & daily life

The phrase "what doesn't kill you makes you stronger" encapsulates the essence of hormesis—an intriguing biological phenomenon where exposure to mild stressors, rather than being detrimental, can elicit adaptive responses that enhance resilience and overall well-being.

Hormesis and Resilience: Hormesis operates on the principle that organisms can benefit from controlled exposure to stressors that are below the threshold of causing harm. In essence, these stressors challenge the system, prompting a response that strengthens and fortifies it against future challenges. This concept aligns with the idea that adversity, when navigated in moderation, can foster adaptability and resilience.

Adaptive Responses to Stress: Consider the analogy of a muscle being stressed during a workout. The stress prompts the muscle to adapt, grow stronger, and become more resilient. Similarly, hormesis involves exposing biological systems to mild stressors, such as exercise, caloric restriction, or environmental challenges, which induce adaptive responses. These responses, ranging from the activation of cellular repair mechanisms to enhanced antioxidant defenses, contribute to the overall fortification of the system.

Learning from Challenges: The phrase also mirrors the concept of learning and growth through overcoming challenges. In the context of hormesis, exposure to stressors becomes a valuable teacher. The body learns to manage and navigate stress, improving its ability to confront similar challenges in the future. This adaptive learning process contributes to the optimization of physiological functions and supports longevity.

Balance and Moderation: It's important to emphasize the critical role of balance and moderation in hormesis. The idea is not to push the system to extremes but to find the sweet spot where the stressor is sufficient to trigger adaptive responses without causing harm. This delicate balance is akin to the fine line between a challenging workout that strengthens the body and one that leads to overtraining.

Hormesis in Everyday Life: The concept of hormesis extends beyond physiological processes to encompass various aspects of life. Just as muscles need a balance of stress and recovery to grow stronger, individuals may benefit from navigating life's challenges with a mindset of resilience and adaptability. Facing adversity, overcoming obstacles, and learning from experiences can contribute to personal growth and development.

In essence, "what doesn't kill you makes you stronger" resonates with the principles of hormesis, highlighting the transformative potential of controlled stress and adversity. As we navigate life's challenges with balance and resilience, we not only endure but emerge stronger and more equipped to face the complexities of the journey ahead.

Hormesis and Resilience: Hormesis operates on the principle that organisms can benefit from controlled exposure to stressors that are below the threshold of causing harm. In essence, these stressors challenge the system, prompting a response that strengthens and fortifies it against future challenges. This concept aligns with the idea that adversity, when navigated in moderation, can foster adaptability and resilience.

Adaptive Responses to Stress: Consider the analogy of a muscle being stressed during a workout. The stress prompts the muscle to adapt, grow stronger, and become more resilient. Similarly, hormesis involves exposing biological systems to mild stressors, such as exercise, caloric restriction, or environmental challenges, which induce adaptive responses. These responses, ranging from the activation of cellular repair mechanisms to enhanced antioxidant defenses, contribute to the overall fortification of the system.

Learning from Challenges: The phrase also mirrors the concept of learning and growth through overcoming challenges. In the context of hormesis, exposure to stressors becomes a valuable teacher. The body learns to manage and navigate stress, improving its ability to confront similar challenges in the future. This adaptive learning process contributes to the optimization of physiological functions and supports longevity.

Balance and Moderation: It's important to emphasize the critical role of balance and moderation in hormesis. The idea is not to push the system to extremes but to find the sweet spot where the stressor is sufficient to trigger adaptive responses without causing harm. This delicate balance is akin to the fine line between a challenging workout that strengthens the body and one that leads to overtraining.

Hormesis in Everyday Life: The concept of hormesis extends beyond physiological processes to encompass various aspects of life. Just as muscles need a balance of stress and recovery to grow stronger, individuals may benefit from navigating life's challenges with a mindset of resilience and adaptability. Facing adversity, overcoming obstacles, and learning from experiences can contribute to personal growth and development.

In essence, "what doesn't kill you makes you stronger" resonates with the principles of hormesis, highlighting the transformative potential of controlled stress and adversity. As we navigate life's challenges with balance and resilience, we not only endure but emerge stronger and more equipped to face the complexities of the journey ahead.

references

Calabrese, Edward J, and Linda A Baldwin. “Hormesis: The Dose-Response Revolution.” Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, vol. 43, no. 1, 28 Nov. 2003, pp. 175–197, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140223.

Mattson, M. P. (2008). Hormesis defined. Ageing Research Reviews, 7(1), 1-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.007

Rattan, S. I. (2008). Hormesis in aging. Ageing Research Reviews, 7(1), 63-78. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.03.002

Ji, Li Li, et al. “Exercise and Hormesis: Activation of Cellular Antioxidant Signaling Pathway.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1067, 1 May 2006, pp. 425–435, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16804022/, https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1354.061.

Peake, Jonathan M., et al. “Modulating Exercise-Induced Hormesis: Does Less Equal More?” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 119, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2015, pp. 172–189, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01055.2014.

Ademowo, O. Stella, et al. “Chapter 6 - Nutritional Hormesis in a Modern Environment.” ScienceDirect, Academic Press, 1 Jan. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128142530000061.

Calabrese, Edward J, et al. “Resveratrol Commonly Displays Hormesis: Occurrence and Biomedical Significance.” Human & Experimental Toxicology, vol. 29, no. 12, 29 Nov. 2010, pp. 980–1015, https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327110383625.

Mattson, Mark P. “Dietary Factors, Hormesis and Health.” Ageing Research Reviews, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 43–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.004.

Ristow, Michael, and Kim Zarse. “How Increased Oxidative Stress Promotes Longevity and Metabolic Health: The Concept of Mitochondrial Hormesis (Mitohormesis).” Experimental Gerontology, vol. 45, no. 6, June 2010, pp. 410–418, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2010.03.014.

Suresh I S Rattan, and Marios Kyriazi. The Science of Hormesis in Health and Longevity. London, Elsevier Academic Press, 2019.

Radak, Zsolt, et al. “Exercise, Oxidative Stress and Hormesis.” Ageing Research Reviews, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 34–42, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1568163707000384, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2007.04.004.

Nitti, Mariapaola, et al. “Hormesis and Oxidative Distress: Pathophysiology of Reactive Oxygen Species and the Open Question of Antioxidant Modulation and Supplementation.” Antioxidants, vol. 11, no. 8, 19 Aug. 2022, p. 1613, https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081613.

Mattson, M. P. (2008). Hormesis defined. Ageing Research Reviews, 7(1), 1-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.007

Rattan, S. I. (2008). Hormesis in aging. Ageing Research Reviews, 7(1), 63-78. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.03.002

Ji, Li Li, et al. “Exercise and Hormesis: Activation of Cellular Antioxidant Signaling Pathway.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1067, 1 May 2006, pp. 425–435, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16804022/, https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1354.061.

Peake, Jonathan M., et al. “Modulating Exercise-Induced Hormesis: Does Less Equal More?” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 119, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2015, pp. 172–189, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01055.2014.

Ademowo, O. Stella, et al. “Chapter 6 - Nutritional Hormesis in a Modern Environment.” ScienceDirect, Academic Press, 1 Jan. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128142530000061.

Calabrese, Edward J, et al. “Resveratrol Commonly Displays Hormesis: Occurrence and Biomedical Significance.” Human & Experimental Toxicology, vol. 29, no. 12, 29 Nov. 2010, pp. 980–1015, https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327110383625.

Mattson, Mark P. “Dietary Factors, Hormesis and Health.” Ageing Research Reviews, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 43–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.004.

Ristow, Michael, and Kim Zarse. “How Increased Oxidative Stress Promotes Longevity and Metabolic Health: The Concept of Mitochondrial Hormesis (Mitohormesis).” Experimental Gerontology, vol. 45, no. 6, June 2010, pp. 410–418, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2010.03.014.

Suresh I S Rattan, and Marios Kyriazi. The Science of Hormesis in Health and Longevity. London, Elsevier Academic Press, 2019.

Radak, Zsolt, et al. “Exercise, Oxidative Stress and Hormesis.” Ageing Research Reviews, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 34–42, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1568163707000384, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2007.04.004.

Nitti, Mariapaola, et al. “Hormesis and Oxidative Distress: Pathophysiology of Reactive Oxygen Species and the Open Question of Antioxidant Modulation and Supplementation.” Antioxidants, vol. 11, no. 8, 19 Aug. 2022, p. 1613, https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081613.