Food intolerance is a common trigger of digestive disorders. Restricting certain foods can dramatically improve these symptoms in sensitive people. In particular, a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates known as FODMAPs is clinically recommended for the management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), leaky gut syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders.

What are FODMAPs?

Fermentable: broken down (fermented) by bacteria

Oligosaccharides: "oligo" means few; "saccharide" means sugar. This includes fructans which are found in grains such as wheat, spelt, rye, and barley, as well as galactans which are found in legumes, and various fruits and vegetables, such as garlic and onions.

Disaccharides: "di" means two. This includes milk, yogurt and soft cheese. Lactose is the main carbohydrate.

Monosaccharides: "mono" means single. This includes various fruit including figs and mangoes, and sweeteners such as honey and agave nectar. Fructose is the main carbohydrate.

And

Polyols: "poly" means many; "ol" means alcohol. This includes certain fruits and vegetables including blackberries and lychee, as well as some low-calorie sugar alcohols like those in sugar-free gum, such as xylitol, sorbitol, maltitol and mannitol.

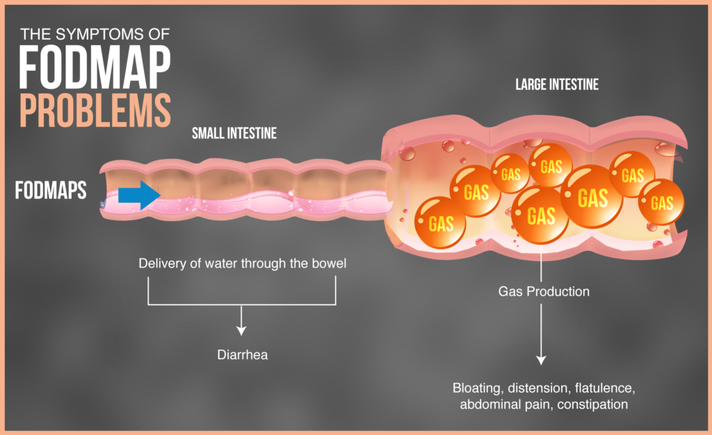

These are short-chain carbohydrates that may be poorly absorbed in the small intestine, and therefore move through your intestines undigested resulting in fermentation. In other words, high-FODMAP foods feed the bacteria in your gut, which can be a good or a bad thing depending on the person. FODMAPs are found in a wide range of foods in varying amounts. Some foods contain just one type, while others contain several.

Oligosaccharides: "oligo" means few; "saccharide" means sugar. This includes fructans which are found in grains such as wheat, spelt, rye, and barley, as well as galactans which are found in legumes, and various fruits and vegetables, such as garlic and onions.

Disaccharides: "di" means two. This includes milk, yogurt and soft cheese. Lactose is the main carbohydrate.

Monosaccharides: "mono" means single. This includes various fruit including figs and mangoes, and sweeteners such as honey and agave nectar. Fructose is the main carbohydrate.

And

Polyols: "poly" means many; "ol" means alcohol. This includes certain fruits and vegetables including blackberries and lychee, as well as some low-calorie sugar alcohols like those in sugar-free gum, such as xylitol, sorbitol, maltitol and mannitol.

These are short-chain carbohydrates that may be poorly absorbed in the small intestine, and therefore move through your intestines undigested resulting in fermentation. In other words, high-FODMAP foods feed the bacteria in your gut, which can be a good or a bad thing depending on the person. FODMAPs are found in a wide range of foods in varying amounts. Some foods contain just one type, while others contain several.

Benefits of a low-fodmap diet

A low-FODMAP diet restricts high-FODMAP foods.

For many people with gastrointestinal symptoms and disoders like IBS, SIBO, leaky gut, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis, consuming a diet high in FODMAPs can result in a variety of symptoms such as stomach pain and distension, bloating, reflux, excessive flatulence, bowel urgency, loose stools or diarrhea, and constipation.

Stomach pain is a hallmark symptom of those sensitive to high-FODMAP foods, and bloating has been found to affect more than 80% of people with IBS (Drossman & Hasler, 2016; Ringel, Williams, Kalilani, Cook, 2009). Both stomach pain and bloating have been shown to significantly decrease with a low-FODMAP diet.

Researchers have observed a reduction in both stomach pain and bloating by 81% and 75%, respectively in FODMAP-sensitive individuals following a low-FODMAP diet (Marsh, Eslick & Elisk, 2016). Other researchers have suggested the diet can help manage flatulence, diarrhea and constipation (Staudacher et al., 2016; Böhn et al., 2015).

For many people with gastrointestinal symptoms and disoders like IBS, SIBO, leaky gut, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis, consuming a diet high in FODMAPs can result in a variety of symptoms such as stomach pain and distension, bloating, reflux, excessive flatulence, bowel urgency, loose stools or diarrhea, and constipation.

Stomach pain is a hallmark symptom of those sensitive to high-FODMAP foods, and bloating has been found to affect more than 80% of people with IBS (Drossman & Hasler, 2016; Ringel, Williams, Kalilani, Cook, 2009). Both stomach pain and bloating have been shown to significantly decrease with a low-FODMAP diet.

Researchers have observed a reduction in both stomach pain and bloating by 81% and 75%, respectively in FODMAP-sensitive individuals following a low-FODMAP diet (Marsh, Eslick & Elisk, 2016). Other researchers have suggested the diet can help manage flatulence, diarrhea and constipation (Staudacher et al., 2016; Böhn et al., 2015).

Altering FODMAP intake has substantial effects on gut microbiota and can effectively reduce gastrointestinal symptoms (Halmos, Christophersen, Bird, Shepherd, Muir, and Gibson, 2016). A low FODMAP diet is emerging as a potential treatment tool for several other health conditions like fibromyalgia, chronic headaches or migraines, and certain auto-immune diseases particularly related to skin conditions. Eating a low FODMAP diet can be beneficial to those who are sensitive because it seems to limit how much food is provided to gut bacteria. A low-FODMAP diet has a lot of applications for helping with different types of gastrointestinal conditions including inflammatory bowel disease likely because it starves bacteria. And even though bacteria can be good for us, in a lot of cases, it seems that—and especially for those that have gastrointestinal problems—an approach that limits, or doesn’t feed bacteria, seems to be a favorable strategy.

Many foods that contain FODMAPs are considered very healthy, and some FODMAPs function like healthy prebiotic fibers, supporting your friendly gut bacteria, or causing gastrointestinal distress if you have dysbiosis (an unhealthy change in the normal bacteria ecology of the intestines).

Many foods that contain FODMAPs are considered very healthy, and some FODMAPs function like healthy prebiotic fibers, supporting your friendly gut bacteria, or causing gastrointestinal distress if you have dysbiosis (an unhealthy change in the normal bacteria ecology of the intestines).

Who should follow a low-fodmap diet?

A low-FODMAP diet is not for everyone. In fact, a low-FODMAP diet should only be temporary for those who find benefits. It is treatment tool, not a lifestyle modification. Unless you have been diagnosed with IBS, research suggests the diet could do more harm than good. This is because most FODMAPs are prebiotics, which means FODMAPs support the growth of good gut bacteria (Meyer & Stasse-Wolthuis, 2009). Most of the research has been in adults, therefore, there is limited support for the diet in children with IBS.

If you have IBS, consider this diet if you:

People who can tolerate these types of carbs should not avoid them. However, for people with a FODMAP intolerance, foods high in these carbs may cause unpleasant digestive issues and should be strictly eliminated or restricted. If you frequently experience digestive upset that lowers your quality of life, FODMAPs should be on your list of top suspects. Though a low-FODMAP diet may not eliminate all digestive problems, chances are high that it may lead to significant improvements.

If you have IBS, consider this diet if you:

- Have ongoing gut symptoms.

- Haven't responded to stress management strategies.

- Haven't responded to first-line dietary advice, including restricting alcohol, caffeine, spicy food and other common trigger foods (McKenzie et al., 2016).

People who can tolerate these types of carbs should not avoid them. However, for people with a FODMAP intolerance, foods high in these carbs may cause unpleasant digestive issues and should be strictly eliminated or restricted. If you frequently experience digestive upset that lowers your quality of life, FODMAPs should be on your list of top suspects. Though a low-FODMAP diet may not eliminate all digestive problems, chances are high that it may lead to significant improvements.

How to follow a low-fodmap diet

Phase 1: Elimination

This stage involves strict avoidance of all high-FODMAP foods. This phase is based on the premise that by elimniating all FODMAPs out of the diet, it gives the gut bacteria a chance to correct any imbalances, and time to heal. A list is provided below. During this phase determine how you respond to restricting the consumption of high-FODMAP foods. This stage should only last about 3–8 weeks, it is not long-term. This is because it's important to include FODMAPs in the diet for optimal gut health.

Some people notice an improvement in symptoms in the first week, while others take the full eight weeks. Once you have adequate relief of your digestive symptoms, you can progress to the second phase.

Phase 2: Reintroduction

This phase involves systematically reintroducing high-FODMAP foods, one by one for three days each (Gibson & Shepherd, 2010). The purpose of this phase is twofold:

It is recommended that you undertake this step with a trained dietitian who can guide you through the appropriate foods. Alternatively, there are many apps and online resources that can help identify which foods to reintroduce. Continue a low-FODMAP diet throughout this stage until phase 3, even if certain high-FODMAP foods are tolerated.

Phase 3: Personalization

This phase is also known as the "modified low-FODMAP diet." In other words, some FODMAPs are still restricted. However, the amount and type are tailored with a bioindividualized approach, specific to you, as identified in stage 2. The importance of this final phase is find a balance and to increase diet variety and flexibility. These qualities are linked with improved long-term compliance, quality of life and gut health (Meyer & Stasse-Wolthuis, 2009).

This stage involves strict avoidance of all high-FODMAP foods. This phase is based on the premise that by elimniating all FODMAPs out of the diet, it gives the gut bacteria a chance to correct any imbalances, and time to heal. A list is provided below. During this phase determine how you respond to restricting the consumption of high-FODMAP foods. This stage should only last about 3–8 weeks, it is not long-term. This is because it's important to include FODMAPs in the diet for optimal gut health.

Some people notice an improvement in symptoms in the first week, while others take the full eight weeks. Once you have adequate relief of your digestive symptoms, you can progress to the second phase.

Phase 2: Reintroduction

This phase involves systematically reintroducing high-FODMAP foods, one by one for three days each (Gibson & Shepherd, 2010). The purpose of this phase is twofold:

- To identify which types of FODMAPs you tolerate. Few people are sensitive to all of them.

- To establish the amount of FODMAPs you can tolerate. This is known as your "threshold level."

It is recommended that you undertake this step with a trained dietitian who can guide you through the appropriate foods. Alternatively, there are many apps and online resources that can help identify which foods to reintroduce. Continue a low-FODMAP diet throughout this stage until phase 3, even if certain high-FODMAP foods are tolerated.

Phase 3: Personalization

This phase is also known as the "modified low-FODMAP diet." In other words, some FODMAPs are still restricted. However, the amount and type are tailored with a bioindividualized approach, specific to you, as identified in stage 2. The importance of this final phase is find a balance and to increase diet variety and flexibility. These qualities are linked with improved long-term compliance, quality of life and gut health (Meyer & Stasse-Wolthuis, 2009).

A List of FODMAP FOODs

This group of fermentable carbohydrates is found in a wide range of foods. A list of high (indicated in red text) and low (indicated in green text) FODMAP foods are listed in the table below. If quantities are given these are the highest amount allowed. Foods listed in the low FODMAP category are not inherently healthier than foods listed in the high FODMAP category, and vice versa. This list is simply indicating the FODMAP property of such foods.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

References

Böhn, L., Störsrud, S., Liljebo, T., Collin, L., Lindfors, P., Törnblom, H. and Simrén, M. (2015). Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome as Well as Traditional Dietary Advice: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology, [online] 149(6), pp.1399-1407.e2. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.054 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Drossman, D. and Hasler, W. (2016). Rome IV ”Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology, [online] 150(6), pp.1257-1261. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Gibson, P. and Shepherd, S. (2010). Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, [online] 25(2), pp.252-258. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06149.x [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Halmos, E., Christophersen, C., Bird, A., Shepherd, S., Muir, J., and Gibson, P. (2016). Consistent Prebiotic Effect on Gut Microbiota With Altered FODMAP Intake in Patients with Crohn's Disease: A Randomised, Controlled Cross-Over Trial of Well-Defined Diets. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology. [online] 7(4), pp.e164-e164. Available at https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2016.22 [Accessed 18 Jan. 2019].

Healthline. (2019). A Beginner's Guide to the Low-FODMAP Diet. [online] Available at: https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/low-fodmap-diet [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

IBSdiets.org. (2019). FODMAP Food List I IBS Diets. [online] Available at: https://www.ibsdiets.org/fodmap-diet/fodmap-food-list/ [Accessed 18 Jan. 2019]

Marsh, A., Eslick, E. and Eslick, G. (2015). Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Nutrition, [online] 55(3), pp.897-906. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00394-015-0922-1 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

McKenzie, Y., Thompson, J., Gulia, P. and Lomer, M. (2016). British Dietetic Association systematic review of systematic reviews and evidence-based practice guidelines for the use of probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, [online] 29(5), pp.576-592. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12386 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Meyer, D. and Stasse-Wolthuis, M. (2009). The bifidogenic effect of inulin and oligofructose and its consequences for gut health. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 63(11), pp.1277-1289. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.64 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Ringel, Y., Williams, R., Kalilani, L. and Cook, S. (2009). Prevalence, Characteristics, and Impact of Bloating Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, [online] 7(1), pp.68-72. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.008 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Staudacher, H., Lomer, M., Anderson, J., Barrett, J., Muir, J., Irving, P. and Whelan, K. (2012). Fermentable Carbohydrate Restriction Reduces Luminal Bifidobacteria and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. The Journal of Nutrition, [online] 142(8), pp.1510-1518. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.159285 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Drossman, D. and Hasler, W. (2016). Rome IV ”Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology, [online] 150(6), pp.1257-1261. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Gibson, P. and Shepherd, S. (2010). Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, [online] 25(2), pp.252-258. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06149.x [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Halmos, E., Christophersen, C., Bird, A., Shepherd, S., Muir, J., and Gibson, P. (2016). Consistent Prebiotic Effect on Gut Microbiota With Altered FODMAP Intake in Patients with Crohn's Disease: A Randomised, Controlled Cross-Over Trial of Well-Defined Diets. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology. [online] 7(4), pp.e164-e164. Available at https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2016.22 [Accessed 18 Jan. 2019].

Healthline. (2019). A Beginner's Guide to the Low-FODMAP Diet. [online] Available at: https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/low-fodmap-diet [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

IBSdiets.org. (2019). FODMAP Food List I IBS Diets. [online] Available at: https://www.ibsdiets.org/fodmap-diet/fodmap-food-list/ [Accessed 18 Jan. 2019]

Marsh, A., Eslick, E. and Eslick, G. (2015). Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Nutrition, [online] 55(3), pp.897-906. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00394-015-0922-1 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

McKenzie, Y., Thompson, J., Gulia, P. and Lomer, M. (2016). British Dietetic Association systematic review of systematic reviews and evidence-based practice guidelines for the use of probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, [online] 29(5), pp.576-592. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12386 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Meyer, D. and Stasse-Wolthuis, M. (2009). The bifidogenic effect of inulin and oligofructose and its consequences for gut health. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 63(11), pp.1277-1289. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.64 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Ringel, Y., Williams, R., Kalilani, L. and Cook, S. (2009). Prevalence, Characteristics, and Impact of Bloating Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, [online] 7(1), pp.68-72. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.008 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Staudacher, H., Lomer, M., Anderson, J., Barrett, J., Muir, J., Irving, P. and Whelan, K. (2012). Fermentable Carbohydrate Restriction Reduces Luminal Bifidobacteria and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. The Journal of Nutrition, [online] 142(8), pp.1510-1518. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.159285 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].