Determining The Daily Dose of Nature Humans are ancient beings living in a modern world. We have been hard-wired through evolution to require and seek contact with nature. A healthy, balanced life, physically and emotionally, requires this contact. Exposure to nature is one of the key foundations to a meaningful life. Indeed, a growing body of evidence overwhelmingly suggests connecting with nature is paramount for optimal health. Connection with nature has been associated with:

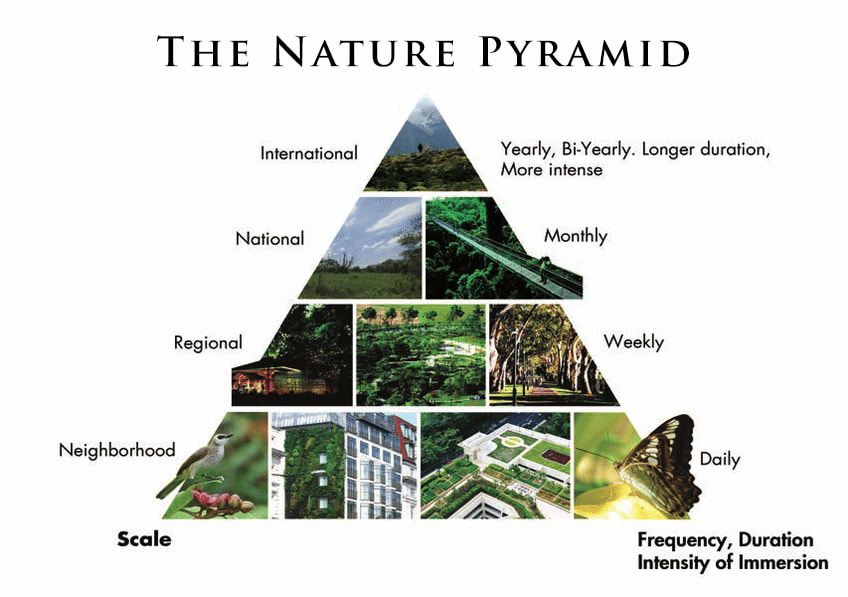

How much exposure to nature and outdoor natural environments is necessary, though, to ensure healthy development? Are there such things as minimum daily requirements of nature? Determining a daily dose of exposure to nature is comparable to the nutrition pyramid that has been touted as a useful guide for the types and quantity of food consumption necessary to be healthy. It has been dubbed the Nature Pyramid,. Referring to the standard nutritional pyramid, towards the top are things that are less healthful in larger quantities—meat, dairy, sugar—and should be consumed in the smallest proportions. Moving down the pyramid are elements in the diet—fruits and vegetables—that should be consumed more frequently and in greater quantity, and then finally the foods that contain the most nutrients that are needed on a daily basis. The Nature Pyramid would work in a similar way. The Nature Pyramid challenges us to think about what the analogous quantities of nature are, and the types of nature exposures and experiences, needed to bring about a healthy life. Exposure to nature, that is direct personal contact with natural, is not an optional thing, but rather is a necessary and important element of a healthy human life. So, like the nutritional pyramid, what specifically is required for optimal health? What amounts of nature, different nature experiences, and exposure to different sorts of nature, together constitute a healthy existence? While researchers may lack the same degree of scientific certainly or confidence regarding a specific quantifiable amount of connection with nature necessary to ensure a healthy life, the pyramid at least begins to ask the right questions. Nature-Deficit Disorder and the Nature Principle In 2005, in Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv introduced the term nature-deficit disorder, not as a medical diagnosis, but as a way to describe the growing gap between humans and nature. Every day, our relationship with nature, or the lack of it, influences our lives. This has always been true. But in the twenty-first century, our survival — or thrival — will require a transformative framework for that relationship, a reunion of humans with the rest of nature. The Nature Principle is an amalgam of converging theories and trends as well as a reconciliation with old truths. This principle holds that a reconnection to the natural world is fundamental to human health, wellness, spirit, and survival. Primarily a statement of philosophy, the Nature Principle is supported by a growing body of theoretical, anecdotal, and empirical research that describes the restorative power of nature — its impact on our senses and intelligence; on our physical, psychological, and spiritual health; and on the bonds of family, friendship, and the multispecies community. What would our lives be like if our days and nights were as immersed in nature as they are in electronics? How can each of us help create that life-enhancing world, not only in a hypothetical future, but right now, for our families and for ourselves? Our sense of urgency grows. In 2008, for the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population lived in towns and cities. The traditional ways that humans have experienced nature are vanishing, along with biodiversity. At the same time, our culture’s faith in technological immersion seems to have no limits, and we drift ever deeper into a sea of circuitry. We consume breathtaking media accounts of the creation of synthetic life, combining bacteria with human DNA; of microscopic machines designed to enter our bodies to fight biological invaders or to move in deadly clouds across the battlefields of war; of virtually-augmented reality; of futuristic houses in which we are surrounded by simulated reality transmitted from every wall. We even hear talk of the “transhuman” or “posthuman” era in which people are optimally enhanced by technology, or of a “postbiological universe” where, as NASA’s Steven Dick puts it, “the majority of intelligent life has evolved beyond flesh and blood intelligence.” This collective disorder threatens our health, our spirit, our economy, and our future stewardship of the environment. Yet, despite what seem prohibitive odds, transformative change is possible. The loss that we feel, this truth that we already know, sets the stage for a new age of nature. In fact, because of the environmental challenges we face today, we may be — we had better be — entering the most creative period in human history, a time defined by a goal that includes but goes beyond sustainability to the renaturing of everyday life. Symptoms of Nature-Deficit Disorder Do you or does someone you know experience nature-deficit disorder (NDD)? In this day in age, it is common to develop mild or severe forms of NDD. Here are several symptoms to look out for:

Interpreting the Nature Pyramid At the bottom of the pyramid are forms of nature and outside life that should form the bulk of our daily experiences. Here there are the many ways in which we might daily enjoy and experience nature, both suburban and urban. As adults, a healthy nature diet requires being outside at least part of each day, walking, strolling, sitting, though it need not be in a remote and untouched national park or otherwise more pristine natural environment. Brief experiences and brief episodes of respite and connection are valuable to be sure: watching birds, hearing the outside sounds of life, and feeling the sun or breeze on one’s arms are important natural experiences, though perhaps brief and fleeting. Some of these experiences are visual and we know that even views of nature from office or home windows provides value. For school aged kids spending the day in a school drenched in full spectrum nature daylight is important and we know the evidence is compelling about the emotional value of this. Every day kids should spend some time outside, sometime playing and running outside, in direct contact with nature, weather, and the elements. Moving from the bottom to the top of the pyramid also corresponds to an important temporal dimension. We need and should want to visit larger more remote parks and natural areas, but for most of us the majority of these larger parks will not be within distance of a daily trip. Each week, we should seek out a local park or area larger than your backyard. Each month, we should seek out a larger, national park. At the top of the pyramid are places and nature experiences that are profoundly important and enriching yet are more likely to happen less frequently, such as remote verdant areas, perhaps only several times a year. They are places of nature where immersion is possible, and where the intensity and duration of the nature experience are likely to be greater. And in between these temporal echelons (from daily to yearly) lie many of the nature opportunities and experiences that happen often on weekends or holidays or every few weeks, and perhaps without the degree of regularity that daily neighborhood nature experiences provide. Like the food items higher on the food pyramid, the sites of nature highest on the Nature Pyramid might best be thought of occasional treats in our nature diet—good for us in small and measured servings, but actually unhealthy if consumed too often or in too great a quantity. For many urbanites from industrialized nations, large amounts of money and effort are expended visiting remote areas, from Patagonia, to the cloud forests of Costa Rica, to the Himalayas. It seems we relish and celebrate the ecologically remote and exotic. While they are deeply enjoyable nature experiences, to be sure, they come at a high planetary cost, as the energy and carbon footprint associated with jetting to these places is large indeed. No longer are such trips appreciated as unique and special “trips of a lifetime,” but fairly common and increasingly pedestrian jaunts to the affluent citizenry of the North. The Nature Pyramid sends a useful signal that travel to faraway nature may as glutinous and unhealthy as eating at the top of the food pyramid.

Suggested dosage for nature exposure A Solution: Shinrin-yoku (Forest Bathing)Forest bathing—or Shinrin-yoku Forest Therapy—is a Japanese healing method that allows an individual to immerse in the forest’s atmosphere. It stills the mind, leaving bathers focused and more alert. Researchers have observed that evergreen trees secret a natural chemical called phytoncide, which directly reduced stress levels and boosted immune systems in subjects (Li, 2009). Researchers (Hansen, Jones and Tocchini, 2017) have determined with the healing components of Shinrin-yoku specifically hones in on the therapeutic effects on:

How to Forest Bath

ReferencesBeatley, T. (2012). Exploring the Nature Pyramid – The Nature of Cities. [online] The Nature of Cities. Available at: https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2012/08/07/exploring-the-nature-pyramid/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2018].

Hansen, M., Jones, R. and Tocchini, K. (2017). Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12), p.851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080851 Kotera, Y., Richardson, M. & Sheffield, D. (2022). Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Addiction 20, 337–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00363-4 Li, Q. (2009). Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 15(1), pp.9-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-008-0068-3 Li Q. (2022). Effects of forest environment (Shinrin-yoku/Forest bathing) on health promotion and disease prevention -the Establishment of "Forest Medicine". Environ Health Prev Med. doi: 10.1265/ehpm.22-00160. PMID: 36328581; PMCID: PMC9665958. Louv, R. (2012). The Nature Principle: Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age. Algonquin Books.

1 Comment

A growing body of evidence suggests and supports the biophilia hypothesis, and demonstrates both the restorative and additive capacity of our biophilic responses. In addition, research suggests that cultivating our innate biophilic tendencies through experiences with natural environments plays a fundamentally important role in addressing the four existential anxieties - meaning in life, isolation, freedom, and death - in addition to addressing two positive existential anxieties - identity and happiness. Existential Positive Psychology (EPP) is concerned with the study of ultimate concerns through integrating both positive and negative aspects of the human condition to create a better future for self and others. EPP stresses the importance of an authentic self-identity. Three types of mature happiness are supported:

Eco-Existential Positive Psychology Nature provides benefits to individual well-being and it is important to recognize the symbiotic, bi-directional relationship between human well-being and the well-being of the larger natural world. Our actions have a profound effect on the ecological system of the Earth. Thus, it is vital (for our own well-being and that of the Earth) that we move away from an anthropocentric, ego-centric view wherein nature provides for our health and well-being "free of charge". We must move toward a eco-centered view, wherein our relationship to the rest of the natural world is seen as a mutually beneficial, cyclical relationship of flourishing. Indeed, empirical evidence supports the existence of such a mutually enhancing relationship between individual human well-being and the larger natural world’s well-being. Exposure to nature and an increased sense of nature connectedness increases human well-being in a variety of ways (Hartig, Kaiser, & Bowler, 2001; Hartig, Kaiser, & Strumse, 2007; Hine, Peacock, & Pretty, 2007; Hoot & Friedman, 2011; Schultz &. Zelezny, 1998). Increased time spent indoors using technology means that we are also losing our connection with the natural world. If this disturbing trend of humankind’s increased distancing from direct experiences in nature continues, the well-being of the planet’s ecosystem will continue to degrade. Experiences in nature play a fundamental role in addressing the six existential anxieties.

Affiliating with nature affords us the opportunity to be fully flourishing human beings — which in turn will allow the larger-than-human natural world an opportunity to fully flourish, as individuals shift from an ego-centered view and lifestyle, to an eco-centered view and lifestyle. It is only through embracing life in its totality that we can uplift humanity and improve the human condition. It is hoped that the perspective of Eco-Existential Positive Psychology will contribute to an expanded awareness of the potential role of nature connectedness and nature involvement in a life well lived. References Hartig, T., Kaiser, F. G., & Bowler, P. A. (2001). Psychological restoration in nature as a positive motivation for ecological behavior. Environment and Behavior, 33, 590–607.

Hartig, T., Kaiser, F. G., & Strumse, E. (2007). Psychological restoration in nature as a source of motivation for ecological behaviour. Environmental Conservation, 34, 291–299. Hine, R., Peacock, J., & Pretty, J. (2007). Evaluating the impact of environmental volunteering on behaviours and attitudes to the environment. Colchester, UK: University of Essex. Hoot, R. E., & Friedman, H. (2011). Connectedness and environmental behavior: Sense of interconnectedness and pro-environmental behavior. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 30, 89–100. Passmore, H. & Howell, A. (2014). Eco-Existential Positive Psychology: Experiences in Nature, Existential Anxieties, and Well-Being. The Humanistic Psychologist, 42, pp.370-388. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2014.920335 Schultz, P. W., & Zelezny, L. C. (1998). Values and proenvironmental behavior: A five-country survey (Mexico,Nicaragua, Peru, Spain, and United States). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 540–558. |

The Awareness domain contains research, news, information, observations, and ideas at the level of self in an effort to intellectualize health concepts.

The Lifestyle domain builds off intellectual concepts and offers practical applications.

Taking care of yourself is at the core of the other domains because the others depend on your health and wellness.

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed