|

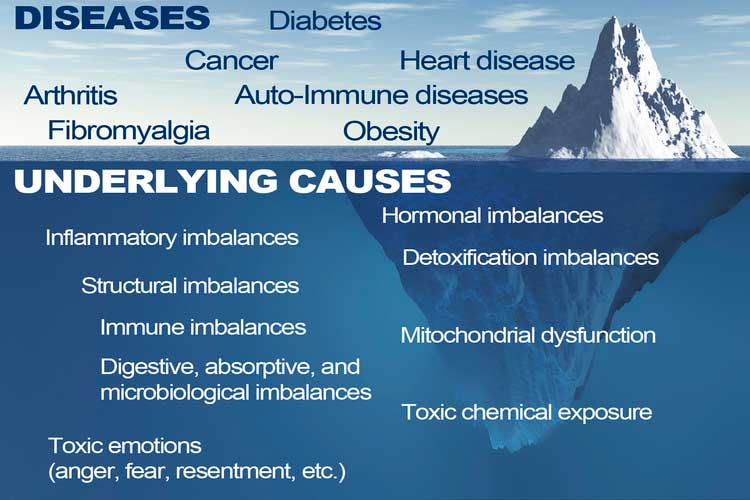

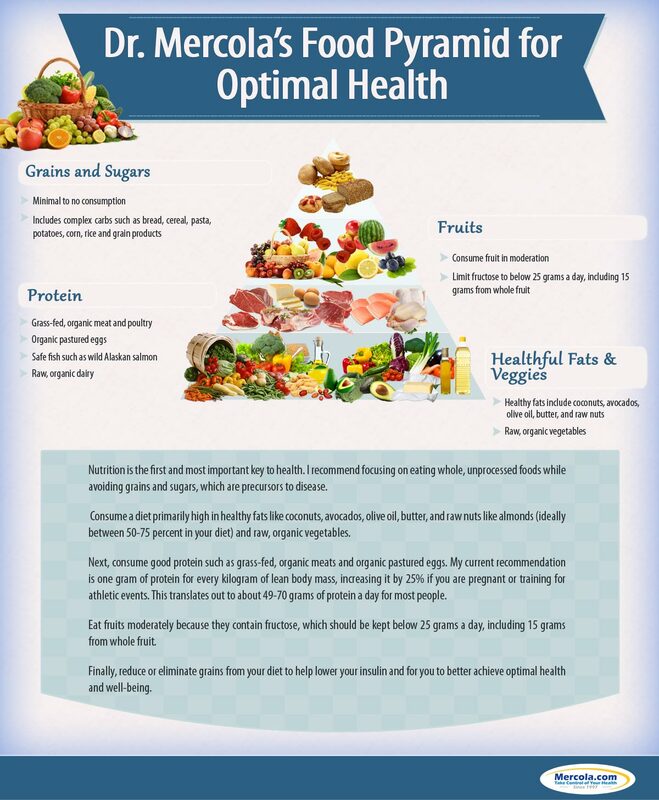

This article challenges the conventional understanding of heart disease, particularly the widely accepted theory that attributes its cause primarily to events occurring in the coronary arteries. Instead, a paradigm shift is proposed, contending that a deeper understanding of heart disease, encompassing angina, unstable angina, and myocardial infarction (heart attack), necessitates a focus on events within the myocardium, the muscular tissue of the heart. Over the past decades, the prevailing belief in the coronary artery theory has led to costly surgical interventions, widespread medication use with questionable benefits, and dietary recommendations that may exacerbate rather than alleviate the problem. By delving into the precise pathophysiological events that underlie heart attacks, we can uncover alternative approaches to prevention and treatment, such as adopting a "Nourishing Traditions"-style diet and utilizing safe and affordable medicines like g-strophanthin. Furthermore, this shift in perspective prompts us to confront broader issues, including the impact of modern lifestyles on human health, the need for a new medical paradigm, and the importance of ecological consciousness. Ultimately, reexamining the root causes of heart disease offers a pathway to addressing this pervasive health challenge and forging a healthier future for all. The information is summarized based on the work of Dr. Thomas Cowan, vice president of the Physicians Association for Anthroposophical Medicine and is a founding board member of the Weston A. Price Foundation. During his career he has studied and written about many subjects in medicine. These include nutrition, homeopathy, anthroposophical medicine, and herbal medicine. Challenging the Conventional model: Revisiting the Causes of Heart AttacksThe traditional understanding of heart attacks, largely centered on arterial blockage due to plaque buildup, has faced challenges in recent years. Initially, it was believed that blockages in the major coronary arteries led to oxygen deficiency in the heart, causing chest pain (angina) and eventually progressing to a heart attack. This simplistic view prompted invasive procedures like angioplasty, stents, and coronary bypass surgery as standard treatments. However, clinical observations and research findings have cast doubts on this approach. Anecdotal evidence (admittedly low quality evidence) from a trial in rural Alabama revealed surprising outcomes among individuals with single artery blockages. Contrary to expectations, less than 10% of those who experienced heart attacks did so in the region of the heart supplied by the blocked artery. Similarly, a comprehensive study conducted by the Mayo Clinic highlighted the limited efficacy of bypass surgery in preventing future heart attacks. While the procedure offered relief from chest pain, it did not significantly reduce the risk of subsequent heart events, except in high-risk patients. Contrary to popular belief, blockages exceeding 90% are often compensated for by collateral blood vessels, which develop over time to ensure uninterrupted blood flow to the heart. This extensive network of collateral vessels serves as a natural bypass system, mitigating the impact of arterial blockages on blood circulation. However, diagnostic procedures like coronary angiograms, which rely on injecting heavy dye into the arteries, often fail to accurately assess the extent of blockages and the true blood flow in the heart. As a result, many patients undergo invasive treatments such as bypass surgery, stents, or angioplasty based on misleading information about the severity of their arterial blockages. Moreover, studies have shown that these procedures provide minimal benefit, if any, to patients, particularly those with minimally symptomatic blockages exceeding 90%. Despite the widespread use of these interventions, their efficacy in restoring blood flow and preventing heart attacks remains questionable. These revelations underscore the need for a reevaluation of conventional treatment strategies and a deeper exploration of the underlying mechanisms behind heart attacks. Rather than focusing solely on arterial blockages, a more holistic approach that considers factors beyond plaque buildup may offer greater insights into the prevention and management of heart disease. Beyond the Coronary Artery TheoryThe prevailing focus in cardiology has long been on the stable, progressing plaque within the coronary arteries, deemed responsible for heart attacks. However, recent insights challenge this notion, redirecting attention to the unpredictable nature of unstable plaques. Unlike their calcified counterparts, unstable plaques are soft and prone to rapid evolution, abruptly occluding arteries and triggering downstream oxygen deficits, angina, and ischemia. These vulnerable plaques are believed to be a blend of inflammatory buildup and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), the primary targets of statin drugs. Consequently, the widespread adoption of statin therapy is advocated as a preventive measure against heart attacks, fueled by angiogram studies purportedly showcasing the prevalence of unstable plaques as the leading cause of myocardial infarctions (MIs). Yet, autopsies and pathology studies present a different narrative. Thrombosis, deemed crucial in precipitating MIs, is found in only a fraction of cases upon meticulous examination. Furthermore, measurements of myocardial oxygen levels during MIs reveal no discernible deficit, challenging the conventional understanding of ischemia as the primary mechanism. While thrombosis does occur in conjunction with MIs, its occurrence in less than half of cases underscores the inadequacy of attributing MIs solely to arterial blockages. The timing of thrombosis, often post-MI, begs the question: what precipitated the event in the first place? These inconsistencies underscore the limitations of existing theories surrounding coronary artery involvement in MIs. As the spotlight shifts away from stable plaques, a pressing question emerges: What truly underlies the genesis of heart attacks? Unveiling the Autonomic Symphony: The Heart's Harmonious BalanceAn accurate understanding of myocardial ischemia necessitates consideration of the primary risk factors associated with heart disease, including gender, diabetes, smoking, and chronic psychological stress. Curiously, none of these risk factors directly implicate coronary artery pathology; instead, they impact capillary health or exert indirect effects. Over the past five decades, key medications in cardiology, such as beta-blockers, nitrates, aspirin, and statins, have demonstrated some benefits for heart patients. However, their mechanisms of action must be scrutinized within a comprehensive theory of myocardial ischemia. A groundbreaking revelation in heart disease prevention and treatment stems from the autonomic nervous system's role in ischemia genesis, as illuminated by heart-rate variability monitoring. The autonomic nervous system comprises two branches—the sympathetic and parasympathetic—responsible for regulating physiological responses. Imbalance between these branches emerges as a significant contributor to heart disease. Studies reveal a notable reduction in parasympathetic activity among patients with ischemic heart disease, particularly preceding ischemic events triggered by physical or emotional stressors. Conversely, abrupt increases in sympathetic activity rarely culminate in ischemia without antecedent parasympathetic decline. Notably, women exhibit stronger vagal activity than men, potentially influencing sex-based disparities in MI incidence. Multiple risk factors, including hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and stress, diminish parasympathetic activity, underscoring the pivotal role of the regenerative nervous system in heart health. Conversely, pharmacological interventions like nitrates, aspirin, and statins stimulate parasympathetic mediators, promoting ANS balance. In essence, while traditional risk factors and interventions influence plaque and stenosis development, their paramount impact lies in restoring ANS equilibrium. Thus, understanding the sequence of events leading to myocardial infarction demands a deeper exploration of autonomic nervous system dynamics. The Underlying pathophysiology of Myocardial IschemiaIn the vast majority of cases, the pathology leading to myocardial infarction (MI) begins with a decreased tonic activity of the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest), often exacerbated by physical or emotional stressors. This reduction prompts an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity, triggering heightened adrenaline production and directing myocardial cells to break down glucose via aerobic glycolysis, rather than their preferred fuel source of ketones and fatty acids (often explaining why patients report feeling tired before a MI). Remarkably, despite these metabolic shifts, no change in blood flow, as measured by the myocardial cell oxygen level (pO2), occurs. The shift towards glycolysis results in a surge of lactic acid production within myocardial cells, a phenomenon observed in nearly all MIs. This surge, coupled with localized tissue acidosis, impedes calcium entry into cells, compromising their contractility. Consequently, localized edema ensues, leading to hypokinesis—the hallmark of ischemic disease—and eventual tissue necrosis characteristic of an MI. Moreover, the ensuing tissue edema alters arterial hemodynamics, escalating sheer pressure and exacerbating plaque instability. This process elucidates the rupture of unstable plaques and their role in exacerbating arterial blockage during critical, acute scenarios. This explanation accounts for all the observable phenomena associated with heart disease. Understanding the etiology of heart disease holds profound implications beyond academic curiosity. It informs therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving parasympathetic activity, fostering holistic approaches to heart health, and challenging prevailing "civilized" industrial lifestyles. Central to this paradigm shift is the recognition of the vital role played by g-strophanthin—a hormone derived from the strophanthus plant. G-strophanthin is an endogenous hormone made in the adrenal cortex from cholesterol, whose production is inhibited by statin drugs, that does two things that are crucial for heart health and are done by no other medicine. G-strophanthin uniquely stimulates the production of acetylcholine, the primary neurotransmitter of the parasympathetic nervous system, while also converting lactic acid—the metabolic poison implicated in ischemic processes—into pyruvate, a preferred myocardial cell fuel. Perhaps this “magic” is why Chinese medicine practitioners say that the kidneys (i.e., adrenals, where ouabain is made) nourish the heart. Embracing this understanding not only guides therapeutic interventions but also underscores the imperative of dietary modifications. A diet abundant in healthful fats and fat-soluble nutrients, while low in processed carbohydrates and sugars, emerges as a cornerstone of heart health—a departure from the industrialized diets synonymous with modern civilization. In essence, unraveling the metabolic symphony orchestrating myocardial ischemia offers a transformative lens through which to perceive heart disease, fostering a holistic approach that transcends conventional paradigms and embraces the profound interconnectedness of mind, body, and environment. referencesGiorgio Baroldi. The Etiopathogenesis of Coronary Heart Disease. CRC Press EBooks, Informa, 20 Jan. 2004. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024.

Sroka K. On the genesis of myocardial ischemia. Z Kardiol. 2004 Oct;93(10):768-83. doi: 10.1007/s00392-004-0137-6. PMID: 15492892. Helfant, R. H., et al. “Coronary Heart Disease. Differential Hemodynamic, Metabolic, and Electrocardiographic Effects in Subjects with and without Angina Pectoris during Atrial Pacing.” Circulation, vol. 42, no. 4, 1 Oct. 1970, pp. 601–610, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11993303., https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.42.4.601. Takase, B., Kurita, A., Noritake, M., Uehata, A., Maruyama, T., Nagayoshi, H., ... & Nakamura, H. (1992). Heart rate variability in patients with diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, and congestive heart failure. Journal of electrocardiology, 25(2), 79-88. Sroka, K., Peimann, C. J., & Seevers, H. (1997). Heart rate variability in myocardial ischemia during daily life. Journal of electrocardiology, 30(1), 45-56. Scheuer, J., & Brachfeld, N. (1966). Coronary insufficiency: relations between hemodynamic, electrical, and biochemical parameters. Circulation Research, 18(2), 178-189. Schmid, P. G., Greif, B. J., Lund, D. D., & Roskoski Jr, R. O. B. E. R. T. (1978). Regional choline acetyltransferase activity in the guinea pig heart. Circulation Research, 42(5), 657-660. Katz, A. M. (1971). Effects of ischemia on the cardiac contractile proteins. Cardiology, 56(1-6), 276-283. Manunta, Paolo, et al. “Endogenous Ouabain in Cardiovascular Function and Disease.” Journal of Hypertension, vol. 27, no. 1, 1 Jan. 2009, pp. 9–18, journals.lww.com/jhypertension/Abstract/2009/01000/Endogenous_ouabain_in_cardiovascular_function_and.3.aspx, https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831cf2c6. Doepp, Manfred. “May Strophanthin Be a Valuable Cardiac Drug ? .” American Journal of Medical and Clinical Research & Reviews, vol. 2, no. 9, 15 Sept. 2023, pp. 1–6, ajmcrr.com/index.php/pub/article/view/75/74, https://doi.org/10.58372/2835-6276.1069. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024. Thayer, J. F., Yamamoto, S. S., & Brosschot, J. F. (2010). The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. International journal of cardiology, 141(2), 122-131.

0 Comments

Research on omega–3 fatty acids has expanded enormously over the past 10 years. Beginning with the mid 1970s, most of the research focused on the role of omega–3fatty acids in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Epidemiological observations, animal studies, clinical intervention studies, and studies at the molecular level firmly established the importance of omega–3 fatty acids, in the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, studies on the mechanisms and the need to balance the omega–6 to the omega–3 ratio for homeostasis and normal development have been carried out at the molecular level and in transgenic animals using lipidomics and informatics. It is now accepted that docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (AA) are essential for brain development during pregnancy, lactation and throughout the life cycle. Recently, studies on brain and retinal function as well as mental health have dominated the field. That DHA can affect brain function and behavior is no longer controversial. The studies on age-related macular degeneration (AMD) given supplemental DHA have revealed significant interactions between DHA and genetic variants. In animal experiments, deficiencies in DHA show impairments in cognitive development correctable by its repletion. Furthermore, the consumption of DHA or fish oil by humans slows cognitive decline in the aged and in subjects with early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and promotes mental development in infants. Over 60 countries worldwide have supplemented infant formula with DHA and AA, yet the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine has not determined the nutritional requirement of DHA.

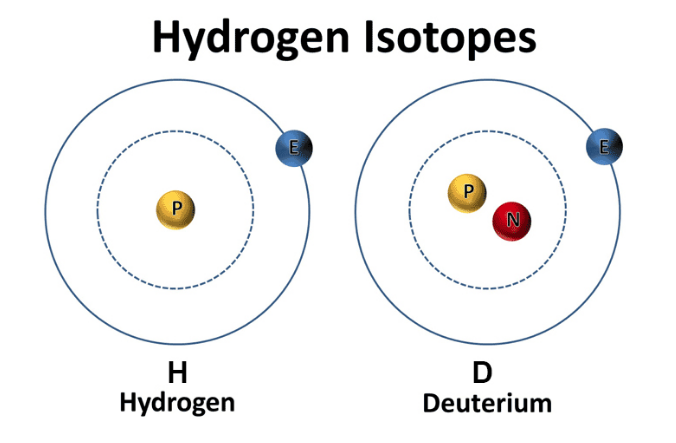

There have been a number of volumes in the series of the World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics (WRND) on various aspects of omega–6 and omega–3 essential fatty acids (EFA) beginning with Volume 66: Health Effects of Omega–3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Sea foods, published in 1991, which truly established the field. It was followed by Volume 75: Fatty Acids and Lipids: Biological Aspects, published in 1994. Volume 83: The Return of Omega-3 Fatty Acids into the Food Supply I. Land-Based Animal Food Products and Their Health Effects, published in 1998. Volume 88: Fatty Acids and Lipids – New Findings, published in 2001. Volume 92: Omega–6/Omega–3 Essential Fatty Acid Ratio: The Scientific Evidence, published in 2003. The present volume 99: Omega–3 Fatty Acids, the Brain and Retina is the sixth in the series, published in 2008. The volume begins with the paper by Artemis P. Simopoulos on Omega–6/Omega–3Essential Fatty Acids: Biological Effects’ which sets the stage for what follows. Dr. Simopoulos emphasizes the changes that have taken place in the food supply that led to high intake of omega–6 and low intake of omega–3 fatty acids, particularly the last 50 years, and the biological effects of the resulting imbalanced omega–6/omega–3 ratio. Major advances have taken place in the concepts of inflammation and proresolution of new lipid mediators, lipoxins, resolvins and protectins discovered by using new approaches mainly lipidomics and informatics. Finally the paper provides an overview of mental illness and eye disease that are presented in detail in the papers that follow. Hydrogen comes in two “flavors”: regular hydrogen, which is actually called protium, and deuterium. Deuterium has all of the same properties as hydrogen, except that it's twice as big and heavy. This is due to an added neutron paired with the proton in the nucleus. Because of this, deuterium is also referred to as "heavy hydrogen," and it actually behaves quite differently from regular hydrogen in chemical reactions and in our bodies. In nature, deuterium helps things grow. For example, deuterium is biologically necessary for growth in babies, teenagers, and developing plants and animals. But once you stop growing, having too much deuterium in your cells can result in mitochondrial dysfunction and lead to premature aging, metabolic problems, and disease. Deuterium is like thick, gluggy oil - when you put thick oil into an engine, the engine sputters, makes strange noises, and eventually breaks. Nature has put systems in place to deplete deuterium and protect the nanomotors, or "little engines," in our cells’ mitochondria from coming into contact with this thick oil. However, the side effects of a modern life - pollution, global warming, processed foods, less healthy lifestyles, etc. - have resulted in many people having way too much deuterium inside their cells. This results in an inability to effectively deplete deuterium and the destruction of our nanomotors. This starts a vicious cycle of deuterium building up and breaking more of our nanomotors. Fewer nanomotors means less energy and more sickness and disease. While deuterium is a natural and essential element, its presence has increased in the modernized environment within the food, atmosphere, and water. Deuterium levels is food will vary based o where that food is grown - deuterium is highest in the equator and in low elevations. Foods high in fat, as well as green plants, including algae and spirulina, which contain high amounts of chlorophyll, are lower in deuterium than fruits, roots, and underground vegetables. As it turns out, GMO foods tainted with glyphosate, as well as processed, synthetically made foods, possess high amounts of deuterium. There are various lifestyle practices that have led to increased deuterium levels including a lack of sleep, particularly deep REM sleep. In addition, breathing shallow and fast via the mouth and chest also contributes to elevated levels of deuterium. Researchers have demonstrated that elevated of deuterium can contribute to:

Learn More About Deuterium Depletion References Understanding Deuterium - The Center for Deuterium Depletion. (2019). Retrieved 24 December 2019, from https://www.ddcenters.com/about-deuterium-2-2-2/

Dr. Rhonda Patrick discusses the differences between different forms of DHA in terms of bioavailability and transport into different cells. She talks about why a specific type of DHA (DHA in phosphatidylcholine) is more readily transported into the brain because it forms DHA-lysophsophatidylcholine. Krill oil and salmon roe both have a slightly higher concentration of DHA-lysophosphatidylcholine. She also talks about astaxanthin, a carotenoid that is unique to krill oil, and has potent antioxidant activity and prevents the oxidation of DHA and EPA.

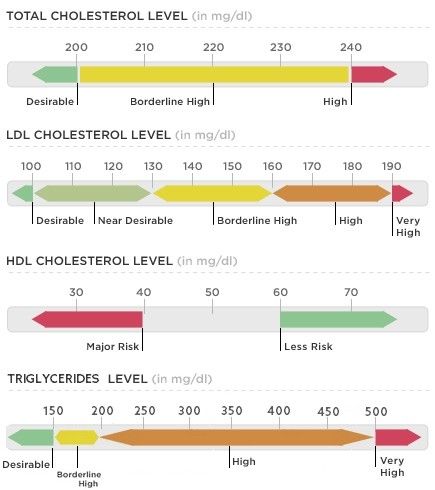

It's that time: time to test your blood. Most blood tests include a fasting lipid panel to assess one's risk of cardiovascular disease. A lipid panel is a test that measures fats and fatty substances used as a source of energy in the body. Lipids include cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL). What Are Triglycerides?

Triglycerides are a powerful cardiovascular risk marker. Elevated triglyceride levels are a hallmark of too many carbohydrates in the diet. 60 percent of fructose is shunted toward the liver, where it is converted to triglycerides (which causes heart disease) (Gundry, 2017). In fact, fructose, which is the sugar found in most processed foods (often in the form of high-fructose corn syrup) can only be metabolized by your liver. If you eat a typical Western-style diet, you consume high amounts of it. The overload of fructose ends up damaging your liver in the same way alcohol and other toxins do (Mercola, 2017). What about Cholesterol? Our culture is obsessed with cholesterol levels, to the point that one in four adults in the U.S. take a statin drug to lower cholesterol levels. Nevertheless, elevated cholesterol levels are rarely a risk factor for heart disease, although elevated triglycerides clearly are. Fortunately, elevated triglycerides can easily be corrected and lowered to an ideal level of below 75 with the proper lifestyle interventions. The following tests can give you a far better assessment of your heart disease risk than your total cholesterol alone:

Influence of Triglycerides on Leptin High triglyceride levels (over 100 mg/dL) is known to cause leptin resistance. Leptin is a hormone located in fat cells, and like most hormones, it's function is complex. Leptin is tied to the coordination of our metabolic, hormonal, and behavioral response to starvation. Leptin essentially controls mammalian metabolism. Leptin decides whether to make us hungry and store more fat or burn fat. In other words, when your stomach is full, fat cells release leptin to tell your brain to stop eating. This is why people with low levels of leptin are prone to overeating. One study observed participants with a 20 percent drop in leptin experienced a 24 percent increase in hunger and appetite, influencing their cravings for calorie-dense, high-carbohydrate foods, especially sweets, salty snacks, and starchy foods. The researchers discovered the drop in leptin was caused by sleep deprivation. Leptin is also a pro-inflammatory molecule - it controls the creation of other inflammatory moleciles in your fat tissue throughout your body. This explains why overweight individuals are susceptible to inflammatory problems. Leptin is ranked highly on the body's chain of command, so imbalances tend to spiral downward and wreak havoc on virtually every system of the body beyond those directly controlled by leptin. Leptin, like insulin, is negatively influenced by carbohydrates. The more refined and processed the carbohydrate, the more imbalanced leptin levels become. When the body is overloaded and overwhelmed by substances that cause continuous surges in leptin, leptin receptors begin to turn off and you become leptin resistant. So even though leptin is now elevated, it doesn't work - it won't signal to your brain that you're full so you can stop eating. Not a single drug or supplement can balance leptin levels. But better sleep, as well as better dietary choices will (Perlmutter, 2013). Causes of High Triglycerides

The main culprit Preventing cardiovascular disease involves reducing chronic inflammation in your body, and a proper diet is an absolute cornerstone. Although saturated fat has taken the blame for causing heart disease for the last several decades, the primary culprit in heart disease is sugar consumption. A 2015 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association concluded that there is " a significant relationship between added sugar consumption and increased risk for cardiovascular mortality." the 15-year study, which included data for 31,000 Americans, found that those who consumed 25 percent or more of their daily calories as added sugars were more than twice as likely to die form heart disease as those who got less than 10 percent of their calories from sugar. On the whole, the odds of dying from heart disease rose in tandem with the percentage of added sugar in the diet regardless of the age, sex, physical activity level, and body mass index (Dhurandhar & Thomas, 2014). A 2014 study came to very similar conclusions. Here, those who consumed the most sugar - about 25 percent of their daily calories - were twice as likely to die form heart disease as those who limited their sugar intake to 7 percent of their total calories (Yang et al., 2013). A 2013 study, published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, looked at the differing effects of high-fat diets versus low-fat diets on blood lipid levels. The study included 32 studies and found that high-fat diets resulted in significantly greater improvements in reductions of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides and benificial increases in HDL cholesterol (Schwingshackl et al., 2013). How to Lower Triglycerides

Consider a Detox

The Dangers of StatinsSo, why are we all obsessed with total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol when we know they aren’t the primary culprits for heart attacks? Because a multi-billion dollar drug industry exists behind the number-one best-selling class of drugs on the market: Statins. Of course, the choice to take medications, if referred by your physician is, and should, always be your choice. However, you have the right to be fully informed of the side effects of consuming anything. With this in mind, it is important to be aware of the unintended side effects of taking statins. A study published in Clinical Cardiology concluded that "Statin therapy is associated with decreased myocardial [heart muscle] function," which often leads to heart failure. The study did not address causes, but it's widely known that statins lower your CoQ10 levels by blocking the pathway involved in cholesterol production -- the same pathway by which Q10 is produced. Statins also reduce the blood cholesterol that transports CoQ10 and other fat-soluble antioxidants. The loss of CoQ10 leads to loss of cell energy and increased free radicals which, in turn, can further damage your mitochondrial DNA, effectively setting into motion an evil circle of increasing free radicals and mitochondrial damage (Mercola, 2011). Moreover, for those at risk of heart disease taking statins who are unwilling or unable to bring down their cholesterol and/or triglyceride levels naturally with dietary changes, the potential for liver or muscle damage should be acknowledged. In addition, the potential for brain-related side effects, such as memory loss and confusion, as well as Parkinson’s-like symptoms is of concern. Statin drugs also appeared to increase the risk of stroke and developing diabetes. In 2013, a study of several thousand breast cancer patients reported that long-term use of statins may as much as double a woman's risk of invasive breast cancer. There are 71 diseases that may be associated with these drugs, and this is only the tip of the iceberg. There are actually over 900 studies showing the risks of statin drugs, which include:

Plant-based diets have been shown to lower cholesterol just as effectively as first-line statin drugs, but without the risks. In fact, the "side effects" of healthy eating tend to be good - less cancer and diabetes risks and protection of the liver and brain (Gregor, 2015). What Should you Eat? ReferencesBaker, A. (2012). What's the real driver of elevated cholesterol? hint: it's not saturated fat! - Nourish Holistic Nutrition. [online] Nourish Holistic Nutrition. Available at: nourishholisticnutrition.com/whats-the-real-driver-of-elevated-cholesterol/ [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019].

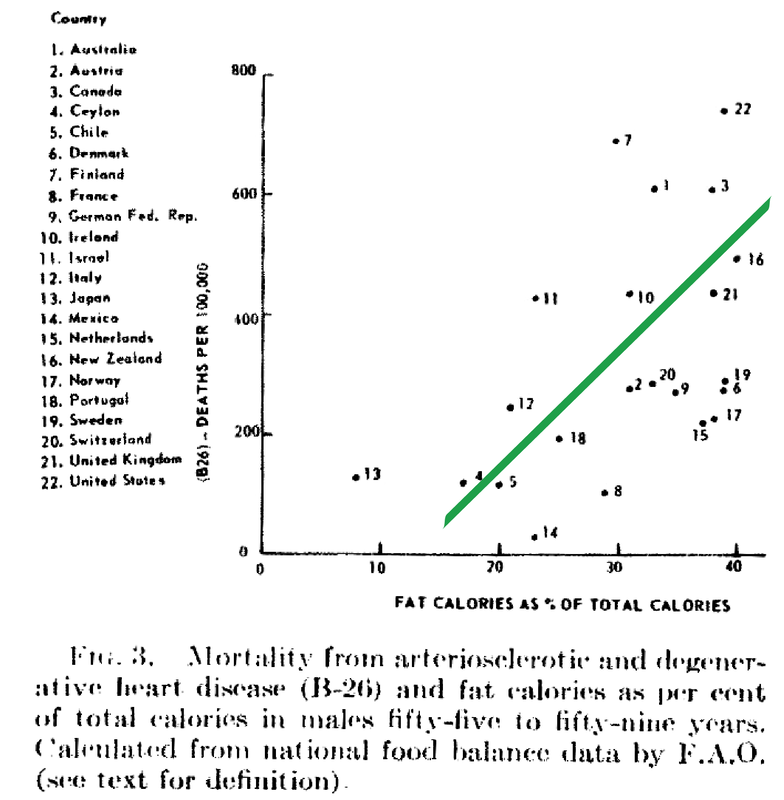

Dhurandhar, N. and Thomas, D. (2015). The Link Between Dietary Sugar Intake and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. JAMA, 313(9), p.959. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.18267 [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Gregor, M. (2015) How Not to Die. London: Pan Books Gundry, S. (2017). The Plant Paradox. New York, NY: Harper Wave Hyman, M. (2016). 7 Ways to Optimize Cholesterol. [online] Dr. Mark Hyman. Available at: https://drhyman.com/blog/2016/01/14/7-ways-to-optimize-cholesterol/ [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Mercola, J. (2017). Fat for Fuel. Carlsbad, CA: Hayhouse Inc. Mercola, J. (2011). New Study Shows Using Statins Actually Harms Heart Function. [online] Mercola.com. Available at: https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2011/06/22/new-study-show-using-statins-actually-worsens-your-heart-function.aspx [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Mercola, J. (2015). Conventional Heart Disease Advice May Make Matters Worse. [online] Mercola.com. Available at: https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2015/08/02/heart-disease-risk-factors.aspx [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Perlmutter, D (2013). Grain Brain. New York, NY: Little Brown Ray, K. et al. (2010). Statins and All-Cause Mortality in High-Risk Primary Prevention. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(12), p.1024. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.182 [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Rubinstein, J., Aloka, F. and Abela, G. (2009). Statin Therapy Decreases Myocardial Function as Evaluated Via Strain Imaging. Clinical Cardiology, 32(12), pp.684-689. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.20644 [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Schwingshackl, S., et al. (2013). Comparison of Effects of Long-Term Low-Fat vs High-Fat Diets on Blood Lipid Levels in Overweight and Obese Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113(12), pp. 1640-61. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.07.010 [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Wallerwellness.com. (2019). Understanding Triglycerides. [online] Available at: https://www.wallerwellness.com/health-and-aging/understanding-triglycerides [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Williams, J. (2017). How To Lower Dangerously High Triglyceride Levels. [online] Renegade Health. Available at: http://renegadehealth.com/blog/2017/03/31/how-to-lower-dangerously-high-triglycerides-levels [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Yang, Q., et al. (2014). Added Sugar Intake and Cardiovascular Diseases Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(4), pp.516-24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13563 [Accessed 8 Feb. 2019]. Despite food manufacturers claiming that refined vegetable oils were healthy, Americans experienced an up-rise in heart disease during the early 20th century. Like many new inventions, few questions were initially posited. Unfortunately, an alternate nutrient took the blame due to the research of a single scientist. In 1951, American physiologist and professor Ancel Keys went to Europe in search of the cause of cardiovascular disease. In his quest, he went to observe the eating habits of individuals living Naples, Italy due to reports of a low prevalence of heart disease. During this time, post-war conditions resulted in finite and unusual circumstances in regards to agriculture and infrastructure. Therefore what Keys perceived as a cultural tradition was dubbed the "Mediterranean diet". Keys observed the residents in Naples consumed primarily pasta and plain pizza, with vegetables, olive oil, cheese, fruit for dessert, a moderate amount of wine, and very little meat (except among individuals belonging to a higher socioeconomic status). Through an informal study measuring cholesterol serum levels among Rotary club members (those who could not afford meat, but could afford cheese) conducted by Keys's wife, whom at the time was a medical technologist, Keys deduced that avoiding meat resulted in a lower incidence of heart attacks. Ancel Keys continued on his biased search for proof that a diet high in saturated fat is correlated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. He eventually compiled data from six more countries with high rates of heart disease and diets typically high in saturated fat. At first glance, Keys's research seemed logical and compelling. The evidence was based on the premise that individuals in America, who consumed high amounts of saturated fat, died from heart disease at a higher rate than individuals in Japan, who consumed low amounts of saturated fat.

Unfortunately, Keys had gained the interest of people in positions of power. Upon President Eisenhower's heart attack in 1955, Keys proposed his theory to the president's primary care physician, Paul Dudley White. Days following, White began to advise to the public to reduce the consumption of saturated fat and cholesterol in an effort to prevent cardiovascular disease. Through his connections and influence, Keys soon joined the nutrition committee of the American Heart Association (AHA) which, based on Keys's research, released a report in 1961 that advised patients with a high risk of cardiovascular disease to reduce their consumption of saturated fat. (Interestingly enough, the AHA began its rise to prominence in 1948, the same year Proctor & Gamble donated over $1.7 million to the organization - resulting in the AHA indebted to Crisco.) In 1961, Time magazine placed Ancel Keys on the front cover touting him as "the twenthiest century's most influential nutrition expert." By 1970, Keys published the Seven Countries Study, which detailed his original research - this study has now been cited in over a million other scientific publications. While Keys associative observations between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease never proved causation, he had won the battle of public opinion. With the help of Ancel Keys, the American medical community and mainstream media has advised consumers to stop eating the animal products that have been consumed for centuries, replacing them with bread, pasta, margarine, low-fat dairy, and vegetable oil. This was the dietary shift that was codified by the United States government in the late 1970s. References Central Committee for Medical And Community Program of the American Heart Association. (1961). Dietary Fat and Its Relation to Heart Attacks and Strokes. Circulation [online] 23, pp.133-36. Available at: https://circ.ahajournals.org/content/circulationaha/23/1/133.full.pdf [Accessed 26 Jan. 2019]

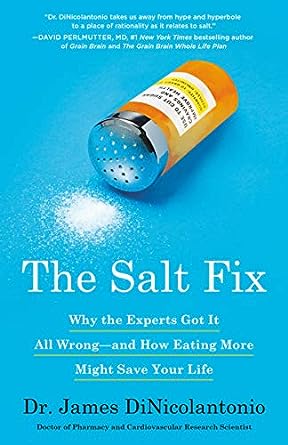

Keys, A. (1953). Atherosclerosis: A Problem in Newer Public Health. Journal of Mt. Sinai Hospital, [online] 20(2), pp.118-39. Keys, A. (1970). Coronary Heart Disease in Seven Countries. Circulation. 41 (1), pp.1186-95. Keys, A. (1995). Mediterranean Diet and Public Health: Personal Reflections. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 61 (6), pp.1321S-1323S. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1321s [Accessed 26 Jan. 2019] Marvin, H. (1964). The 40 Year War on Heart Disease. New York: American Heart Association. Mercola, J. (2017). Fat For Fuel. Carlsbad, California: Hay House. Teichholz, N. (2014). The Big Fat Surprise. New York: Simon & Schuster, pp.32-33. A leading cardiovascular research scientist upends the low-salt myth, proving that salt may be one solution to—rather than a cause of—our nation’s chronic disease crises.

Sure to change the national conversation about this historically treasured substance, The Salt Fix elegantly and accessibly weaves the research into a fascinating new understanding of salt’s essential role in your health and what happens when you aren’t getting enough—with far-reaching, even heart-stopping, implications. We’ve all heard the recommendation: eat no more than a teaspoon of salt a day for a healthy heart. But there’s one big problem with this: the vast majority of us don’t need to eat low-salt diets. In fact, for most of us, more salt would be better for our health, rather than less. (Not to mention, much tastier.) Scientific research suggests that the optimal range for sodium intake is 3 to 6 grams per day (about 1 ⅓ - 2 ⅔ teaspoons of salt) for healthy adults. Now, Dr. James DiNicolantonio reveals the incredible, often baffling story of how salt became unfairly demonized—a never-before-told, century-spanning drama of competing egos and interests. Not only have we gotten it wrong, we’ve gotten it exactly backwards: eating more salt can help protect you from a host of ailments, including internal starvation, insulin resistance, diabetes, and even heart disease. (The real culprit? Another white crystal—sugar.) Dr. DiNicolantonio in The Salt Fix shows how eating the right amount of this essential mineral will help you beat sugar cravings, achieve weight loss, improve athletic performance, increase fertility, and thrive with a healthy heart. James J. DiNicolantonio, Pharm. D., is a respected cardiovascular research scientist, doctor of pharmacy at Saint Luke's Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Missouri, and the associate editor of British Medical Journal's (BMJ) Open Heart. He is the author or coauthor of approximately 200 publications in medical literature. His research has been featured in The New York Times, ABC’s Good Morning America, TIME, Fox News, U.S. News and World Report, Yahoo! Health, BBC News, Daily Mail, Forbes, National Public Radio, and Men’s Health, among others.

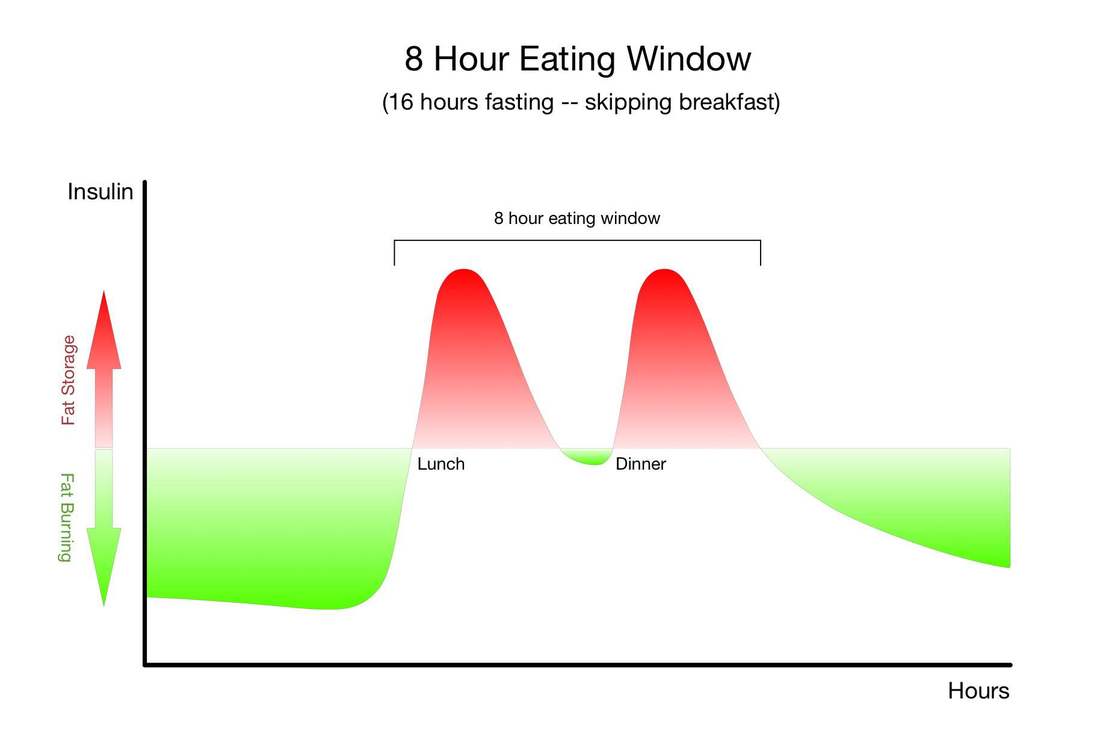

Physiologically, fasting:

The only other strategy that has so many research-baked benefits for longevity is long-term calorie restriction, which requires a significant long-term reduction in the amount of food you eat so that you are essentially living on the brink of starvation. Compliance with calorie-restricted diets is abysmal. Fortunately, there are many ways to fast, and there is likely a form of fasting out there that you will be able to tolerate and incorporate into your life. It's important for you to remember that fasting can provide nearly identical benefits without the pain, suffering, and compliance challenges of calorie restriction. Instead of regulating how much food you eat, as with long-term calorie restriction, you only need to modify when you eat - and of course wisely choose the foods you do eat.Simply cycling between periods of eating and fasting on a daily, weekly, or monthly schedule has been shown to provide many of the same benefits as long-term calorie restriction. Choosing when to eat and when to fast in this way is known as "intermittent fasting." "Don't eat less - eat less often." |

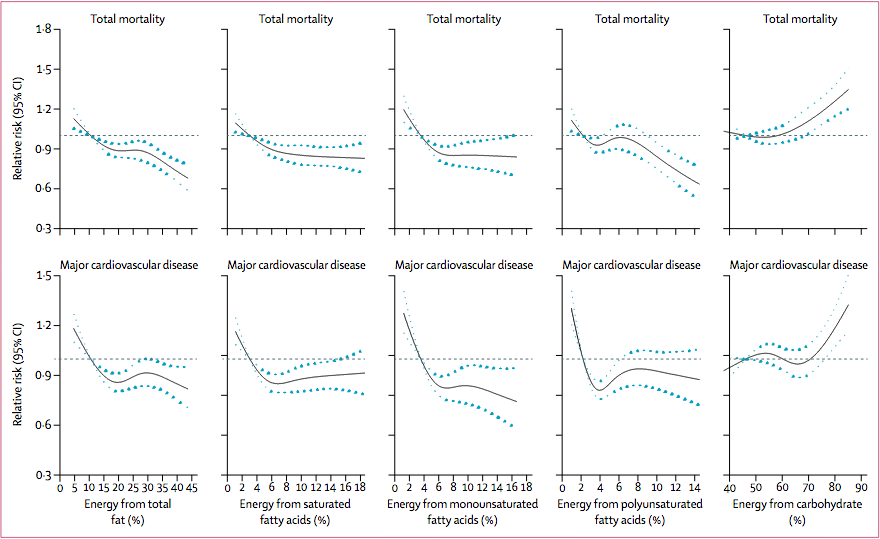

| It is well established that diet is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease and other non-transmittable diseases. Current dietary guidelines recommend a low-fat diet (<30% of energy) and limiting saturated fatty acids to less than 10% of energy intake by replacing them with unsaturated fatty acids, while consuming 45-65% of of total calories from carbohydrates. However, results from an international study, spanning more than a decade, are prompting experts to reconsider global dietary guidelines. |

Overall, the researchers found that high carbohydrate intake (more than 60% of energy) was associated with higher risk of total mortality, whereas total fat and individual types of fat were related to lower total mortality. Total fat and types of fat were not associated with cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, or cardiovascular disease mortality, whereas saturated fat had an inverse association with stroke.

For decades, dietary guidelines have focused on reducing total fat and saturated fatty acid intake, based on the presumption that replacing saturated fatty acids with carbohydrate and unsaturated fats will lower LDL cholesterol and should therefore reduce cardiovascular disease events. This focus is largely based on selective emphasis on some observational and clinical data, despite the existence of several randomized trials and observational studies that do not support these conclusions.

Results of the Study

- Individuals who consumed a very high carbohydrate diet (at least 60% of energy), especially from refined sources (such as white rice and white bread), were associated with increased risk of total mortality and cardiovascular events.

- An inverse association between total fat and total mortality.

- Individuals consuming a higher glycemic load, such as refined carbohydrates, were associated with a higher risk of stroke

- An inverse association between saturated fatty acid intake, total mortality, non-

cardiovascular disease mortality, and stroke risk without any evidence of an increase in major cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular disease mortality. - An inverse association between monounsaturated fatty acid intake and total mortality.

Recommendations and Take Away

Limitations of the Study

- The researchers used food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) to estimate participants’ dietary intake which is not a measure of absolute intake, but is suited for classifying individuals into intake categories and is the most commonly used approach for assessing intake in epidemiological studies.

- Dietary intakes were measured only at baseline, and it is possible that dietary changes might have occurred during the follow-up period. Even if major dietary changes occurred after the baseline assessment, they probably would have weakened the observed associations.

- There is potential for social desirability bias and individuals who are health conscious might also adopt other healthy lifestyles. However, if this were the case, the researchers would not expect to see different associations for the different outcomes.

- As with any observational cohort study, observed associations might be in part due to residual confounding (eg, differences in the ability to afford fats and animal proteins, which are more expensive than carbohydrates) despite extensive adjustment for known confounding factors.

- The researchers were unable to measure trans-fat intake which might affect our results, especially our replacement analyses.

- FFQ assessed polyunsaturated fatty acid intake mainly from foods, rather than from vegetable oils, which might have different health effects than those observed in the study.

The researchers declare no conflicts of interests

References

Dehghan, M., Mente, A., Zhang, X., Swaminathan, S., Li, W., Mohan, V., Iqbal, R., Kumar, R., Wentzel-Viljoen, E., Rosengren, A., Amma, L., Avezum, A., Chifamba, J., Diaz, R., Khatib, R., Lear, S., Lopez-Jaramillo, P., Liu, X., Gupta, R., Mohammadifard, N., Gao, N., Oguz, A., Ramli, A., Seron, P., Sun, Y., Szuba, A., Tsolekile, L., Wielgosz, A., Yusuf, R., Hussein Yusufali, A., Teo, K., Rangarajan, S., Dagenais, G., Bangdiwala, S., Islam, S., Anand, S., Yusuf, S., Diaz, R., Orlandini, A., Linetsky, B., Toscanelli, S., Casaccia, G., Cuneo, J., Rahman, O., Yusuf, R., Azad, A., Rabbani, K., Cherry, H., Mannan, A., Hassan, I., Talukdar, A., Tooheen, R., Khan, M., Sintaha, M., Choudhury, T., Haque, R., Parvin, S., Avezum, A., Oliveira, G., Marcilio, C., Mattos, A., Teo, K., Yusuf, S., Dejesus, J., Agapay, D., Tongana, T., Solano, R., Kay, I., Trottier, S., Rimac, J., Elsheikh, W., Heldman, L., Ramezani, E., Dagenais, G., Poirier, P., Turbide, G., Auger, D., De Bluts, A., Proulx, M., Cayer, M., Bonneville, N., Lear, S., Gasevic, D., Corber, E., de Jong, V., Vukmirovich, I., Wielgosz, A., Fodor, G., Pipe, A., Shane, A., Lanas, F., Seron, P., Martinez, S., Valdebenito, A., Oliveros, M., Wei, L., Lisheng, L., Chunming, C., Xingyu, W., Wenhua, Z., Hongye, Z., Xuan, J., Bo, H., Yi, S., Jian, B., Xiuwen, Z., Xiaohong, C., Tao, C., Hui, C., Xiaohong, C., Qing, D., Xiaoru, C., Qing, D., Xinye, H., Bo, H., Xuan, J., Jian, L., Juan, L., Xu, L., Bing, R., Yi, S., Wei, W., Yang, W., Jun, Y., Yi, Z., Hongye, Z., Xiuwen, Z., Manlu, Z., Fanghong, L., Jianfang, W., Yindong, L., Yan, H., Liangqing, Z., Baoxia, G., Xiaoyang, L., Shiying, Z., Rongwen, B., Xiuzhen, T., Dong, L., Di, C., Jianguo, W., Yize, X., Tianlu, L., Peng, Z., Changlin, D., Ning, L., Xiaolan, M., Yuqing, Y., Rensheng, L., Minfan, F., Jing, H., Yu, L., Xiaojie, X., Qiang, Z., Lopez-Jaramillo, P., Lopez, P., Garcia, R., Jurado, L., Gómez-Arbeláez, D., Arguello, J., Dueñas, R., Silva, S., Pradilla, L., Ramirez, F., Molina, D., Cure-Cure, C., Perez, M., Hernandez, E., Arcos, E., Fernandez, S., Narvaez, C., Paez, J., Sotomayor, A., Garcia, H., Sanchez, G., David, T., Rico, A., Mony, P., Vaz, M., Bharathi, A., Swaminathan, S., Kurpad, K., Jayachitra, K., Kumar, N., Hospital, H., Mohan, V., Deepa, M., Parthiban, K., Anitha, M., Hemavathy, S., Rahulashankiruthiyayan, T., Anitha, D., Sridevi, K., Gupta, R., Panwar, R., Mohan, I., Rastogi, P., Rastogi, S., Bhargava, R., Kumar, R., Thakur, J., Patro, B., Lakshmi, P., Mahajan, R., Chaudary, P., Kutty, V., Vijayakumar, K., Ajayan, K., Rajasree, G., Renjini, A., Deepu, A., Sandhya, B., Asha, S., Soumya, H., Kelishadi, R., Bahonar, A., Mohammadifard, N., Heidari, H., Yusoff, K., Ismail, T., Ng, K., Devi, A., Nasir, N., Yasin, M., Miskan, M., Rahman, E., Arsad, M., Ariffin, F., Razak, S., Majid, F., Bakar, N., Yacob, M., Zainon, N., Salleh, R., Ramli, M., Halim, N., Norlizan, S., Ghazali, N., Arshad, M., Razali, R., Ali, S., Othman, H., Hafar, C., Pit, A., Danuri, N., Basir, F., Zahari, S., Abdullah, H., Arippin, M., Zakaria, N., Noorhassim, I., Hasni, M., Azmi, M., Zaleha, M., Hazdi, K., Rizam, A., Sazman, W., Azman, A., Khatib, R., Khammash, U., Khatib, A., Giacaman, R., Iqbal, R., Afridi, A., Khawaja, R., Raza, A., Kazmi, K., Zatonski, W., Szuba, A., Zatonska, K., Ilow, R., Ferus, M., Regulska-Ilow, B., Rózanska, D., Wolyniec, M., Alkamel, Ali, M., Kruger, M., Voster, H., Schutte, A., Wentzel-Viljoen, E., Eloff, F., de Ridder, H., Moss, H., Potgieter, J., Roux, A., Watson, M., de Wet, G., Olckers, A., Jerling, J., Pieters, M., Hoekstra, T., Puoane, T., Igumbor, E., Tsolekile, L., Sanders, D., Naidoo, P., Steyn, N., Peer, N., Mayosi, B., Rayner, B., Lambert, V., Levitt, N., Kolbe-Alexander, T., Ntyintyane, L., Hughes, G., Swart, R., Fourie, J., Muzigaba, M., Xapa, S., Gobile, N., Ndayi, K., Jwili, B., Ndibaza, K., Egbujie, B., Rosengren, A., Boström, K., Gustavsson, A., Andreasson, M., Snällman, M., Wirdemann, L., Oguz, A., Imeryuz, N., Altuntas, Y., Gulec, S., Temizhan, A., Karsidag, K., Calik, K., Akalin, A., Caklili, O., Keskinler, M., Erbakan, A., Yusufali, A., Almahmeed, W., Swidan, H., Darwish, E., Hashemi, A., Al-Khaja, N., Muscat-Baron, J., Ahmed, S., Mamdouh, T., Darwish, W., Abdelmotagali, M., Awed, S., Movahedi, G., Hussain, F., Al Shaibani, H., Gharabou, R., Youssef, D., Nawati, A., Salah, Z., Abdalla, R., Al Shuwaihi, S., Al Omairi, M., Cadigal, O., Alejandrino, R., Chifamba, J., Gwaunza, L., Terera, G., Mahachi, C., Murambiwa, P., Machiweni, T. and Mapanga, R. (2017). Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32252-3

Archives

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

September 2023

August 2023

June 2023

October 2022

July 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

September 2020

August 2020

March 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

Categories

All

5G

Adductors

Anxiety

Autism

Ayurveda

Big Pharma

Body

Breathing

Cancer

Cannabis

Carbohydrates

Cardiovascular Disease

Children

Chronic Disease

Cognition

Consciousness

Coronavirus

Covid

Cryotherapy

Depression

Deuterium

Diet

Dietary Guidelines

EMFs

Emotions

Endocrine Disruptors

Environment

Exercise

Farming

Fasting

Fats

Fluoride

Food

Food Like Product

Food-like Product

Forest

Gardening

Genetics

Glyphosate

GMOs

Hamstrings

Healing

Health

Herbalism

Hormones

HRV

Immunity

Infertility

Laughter

Lockdowns

Loneliness

Longevity

Masks

Meditation

Metabolism

Microbiome

Microwave Radiation

Mind

Mortality

Musculoskeletal System

Nature

Neuroplasticity

Nutrition

Omega 3

Omega-3

Organic

Pelvis/Thigh

Pesticides

Physical Therapy

Placebo

Pollution

Positive

Pregnancy

Prevention

Processed Foods

Psi

Quadriceps

Research

Retirement

Salt

Sleep

Spine/Thorax

Spirit

Stress

Sugar

Technology

Touch Screens

Toxicity

Vaccines

Well Being

Well-Being

RSS Feed

RSS Feed